(Nairobi) – Kenya’s presidential election on August 8, 2017 was marred by serious human rights violations, including unlawful killings and beatings by police during protests and house-to-house operations in western Kenya, Human Rights Watch said today. At least 12 people were killed and over 100 badly injured.

Kenyan authorities should urgently investigate the crimes, and ensure that officers found to have used excessive force are held to account.

“The brutal crackdown on protesters and residents in the western counties, part of a pattern of violence and repression in opposition strongholds, undermined the national elections,” said Otsieno Namwaya, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “People have a right to protest peacefully, and Kenyan authorities should urgently put a stop to police abuse and hold those responsible to account.”

Human Rights Watch conducted research in western Kenya during and after the election. Researchers interviewed 43 people, including victims of police beatings and shootings, in Kisumu and Siaya counties; examined bodies in mortuaries in Kisumu and Siaya counties; and visited victims at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (Russia Hospital) in Kisumu.

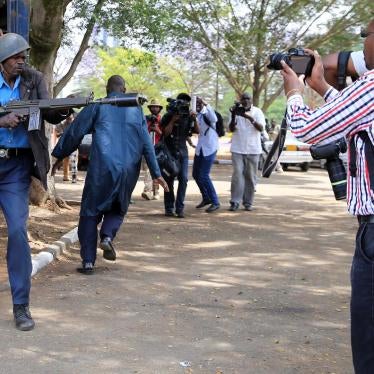

On August 11, following the announcement of Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory at the polls, opposition supporters in Nairobi, Coast, and the western counties of Kisumu, Siaya, Migori, and Homabay protested with chants of “Uhuru must go.” Police responded in many areas with excessive force, shooting and beating protesters in Nairobi and western Kenya or carrying out abusive house-to-house operations.

On August 12, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights reported that the police had killed at least 24 people nationwide, including one in Kisumu and 17 in Nairobi. The number is most likely much higher, as Kenyan media were slow in reporting on the violence and families have been afraid to speak out.

Mild protests and political tension surfaced in parts of western Kenya and Nairobi on August 9, following allegations by the opposition leader, Raila Odinga, that the electoral commission’s system had been hacked and polling results manipulated in favor of Kenyatta. The protests intensified on August 11, when the electoral commission declared Kenyatta the winner. Odinga has challenged the results in court, with the verdict due by September 1.

In western Kenya, police fired teargas canisters and water cannons to disperse protesters, who threw stones and other crude objects at police. Protesters also blocked roads with stones, burned tires, and lit fires on the roads.

On August 11 and 12, police carried out house-to-house operations. Residents said that police asked for any men in the house and beat or shot them. Police also fired teargas canisters and water cannons in residential areas. Human Rights Watch confirmed through multiple sources that police killed at least 10 people, including a 6-month-old baby, in Kisumu county alone. In neighboring Siaya county, police fatally shot a protester near the town of Siaya and beat a 17-year-old boy to death in the outskirts of Ugunja, as they pursued crowds of protesters into the villages. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that protesters were armed or acted in a manner that could justify the use of such force.

In the town of Kisumu, hospital staff and county government officials confirmed that at least 100 people, mostly men, were seriously injured in the beatings and shootings. Many others did not go to a hospital for treatment for fear of being further targeted or arrested. As of August 17, at least 92 people with serious injuries, including 3 women who said police raped them, had not sought any medical help, according to Edris Omondi, the chairperson of the makeshift Kisumu county Disaster Management Center that was registering those affected by the violence and police abuses.

Residents of Obunga, Nyalenda, Nyamasaria, Arina, Kondele, and Manyatta neighborhoods in Kisumu told Human Rights Watch that during house-to-house operations, officers broke down doors; beat residents; stole money, phones and television sets; and sexually harassed women. Many town residents fled to a nearby school for the night, only to return to find their possessions looted, presumably by police. Police denied any role in the looting and claimed that criminals were responsible.

On August 12, the acting cabinet secretary for interior and coordination of the national government, Dr. Fred Matiang’i, denied that police used live bullets or excessive force against protesters and blamed criminals for looting. “Some criminal elements took advantage of the situation to loot property,” he said. “The police responded and normalcy has returned in the affected areas. The right to demonstrate should be carried out in a peaceful manner and without destroying property.

International law and Kenya’s own constitution protect the right to freedom of assembly and expression, and prohibit excessive use of force by law enforcement officials. The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms say that law enforcement officials should use force only in proportion to the seriousness of the offense, and the intentional use of lethal force is permitted only when strictly unavoidable to protect life.

The principles also say that governments should ensure that arbitrary or abusive use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials is punished as a criminal offense. Superior officers should be held responsible if they knew, or should have known, that personnel under their command resorted to the unlawful use of force and firearms, but did not take all measures in their power to prevent, suppress, or report such use.

Kenyan police have a long history of using excessive force against protesters, especially in the western counties such as Kisumu, Siaya, Migori, and Homabay, where Odinga has had solid support for over 20 years. In the 2007 post-election violence, during which more than 1,100 people were killed, most of the more than 400 people shot by police were in the Nyanza region, which includes those counties.

In 2013, Human Rights Watch documented at least five cases of apparently unlawful police killings of demonstrators in Kisumu protesting a Supreme Court decision that affirmed Kenyatta’s election as president. And in June 2016, police killed at least five and wounded another 60 demonstrators in Kisumu, Homabay, and Siaya counties who called for the firing of electoral commission officials implicated in cases of corruption abroad.

Yet, accountability for police abuses has been sorely missing, Human Rights Watch said.

The Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), a civilian police accountability institution, has investigated many abuses in the Nyanza region. In September 2016, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions opened a public inquest into the 2013 police shootings in Kisumu. But these efforts have not resulted in any prosecutions of the police officers implicated in what appeared to be unlawful killings and maiming of protesters in western Kenya.

The government of Kenya should publicly acknowledge and condemn any and all recent unlawful and unnecessary police killings and shootings, Human Rights Watch said. Donors to the Kenyan government should support police accountability systems, particularly the Independent Policing Oversight Authority, in investigating the recent violence and releasing their findings to the public.

“With tensions still running high as the country awaits the court’s decision on the opposition’s petition, Kenyan authorities need to be vigilant in preventing more police abuses and upholding the right to peaceful protest,” Namwaya said. “Kenyans should be able to express their grievances without being beaten or killed by police.”

Post-Election Police Operations

On August 8, Kenya held its second presidential election since the disputed 2007 election that resulted in violence in which more than 1,100 people were killed and another 650,000 displaced. Within hours after the initial results started streaming live on television on August 9, 2017, but before the electoral commission announced Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory, the leading opposition candidate, Raila Odinga, expressed concerns that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission’s (IEBC) server had been hacked and presidential results that were streaming in had been manipulated.

Following these allegations and the August 11 declaration that Kenyatta had won, opposition supporters in the capital, Nairobi, in western Kenya, and in parts of the coastal region took to the streets in protest. Victims and witnesses told Human Rights Watch that Kenyan police responded violently, hurling teargas canisters and water cannons in residential areas and using lethal fire.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 43 people in Kisumu and Siaya counties about the events, including, among others, victims and witnesses.

On August 11 and 12, according to victims of police beatings and witnesses to the events, police conducted house-to-house operations in the town of Kisumu, using lethal fire against unarmed protesters, violently storming into homes at night, looking for and beating mainly men, extorting money, stealing electronic goods, and in some cases raping women. In Siaya county, police dispersed crowds of protesters at market centers along Kisumu’s Busia Road and pursued them into villages, throwing teargas into homes and beating residents.

Killings by Police in Kisumu and Siaya Counties

Human Rights Watch interviewed family members and witnesses to at least 12 killings by police, 10 in Kisumu county and two in neighboring Siaya county, in the former Nyanza region of western Kenya. Some occurred as police tried to suppress protests, but others occurred during house-to-house operations or in places with no protests.

While some victims were protesters, others were not and were either caught up in the violence or attacked inside their homes. A 33-year-old man from the Obunga neighborhood said police found him and friends standing outside his house on the morning of August 12, and started shooting at them without talking to them. “They arrived in a Land Cruiser that was followed in the air by a helicopter and they just started firing at us: They did not even want to know what we were doing outside my house. We had to run for dear life.”

In Kisumu county, Human Rights Watch saw six bodies that witnesses described as victims of police shootings and beatings, four of them in the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Hospital, also known as the Russia Hospital, mortuary. Two young men in their teens from the Nyaori area had gunshot wounds. A witness said that police came into the homes of the two teens, Onyango Otieno and Ochieng Gogo, on the morning of August 12, beat them, then told them to run away and shot them in the back: “As they were running away, police shot them at the back and took their bodies away.”

According to relatives and witnesses, two others died from police beatings on the night of August 11 in the Kondele area. Lennox Ochieng, a 27-year-old man, was beaten to death by police in his house in the Kondele neighborhood. Another body, described in hospital records as “unknown male alias Kimoko,” had bullet wounds, but witnesses could not describe the circumstances of his death.

Another victim, 35-year-old David Ochieng, was shot while he was protesting on the night of August 11. An acquaintance who was with him during protests said he saw police shoot him around 11 p.m. as he threw stones at the police. “The bullet went through his right ear and came out through the other side,” the acquaintance said. “He could not talk at the time we took him to hospital but he could communicate through signs. He gave us the phone contacts of his next of kin by writing in the air using signs.” Ochieng died in the hospital on the morning of August 13.

Six-month-old Samantha Pendo was another victim. Eye witnesses told researchers that on August 11, police violently attacked her family, kicking, slapping, and beating with gun butts and batons everyone in the house, including the baby. A nurse at Aga Khan Hospital said that the baby had a fractured skull and was in critical condition. The baby died in the hospital on August 16.

Police carried out the house-to-house operations in Kisumu, as well as villages in Kisumu and Siaya counties. Residents of the village of Dago said that on the night of August 11, police officers attached to the Dago police post, 25 kilometers north of Kisumu, started firing at villagers strolling on the road, unaware of the protests in other parts of Kisumu. In the process, they said a police officer shot 21-year-old Vincent Omondi Ochieng, who was working with Elections Observations Group (ELOG), a Kenyan organization that has observed the past two elections.

“Vincent and his younger uncle were returning from watching a football game at a few minutes past midnight when police officers, who were hiding at Bar Union Primary School, started shooting at them,” said his aunt, who lived nearby. “His uncle told us that Vincent was on phone and the first two shots startled him and he fell. It was the third shot that killed him.” Human Rights Watch researchers observed the bullet wound in his chest in the heart area.

While Human Rights Watch confirmed the killings described above, the death toll in Kisumu county could be higher. Many witnesses and family members were afraid of speaking up or even going to the hospital, while others said they could not immediately establish the whereabouts of their relatives.

In Kisumu’s Nyamasaria neighborhood, for example, witnesses and relatives of a young man who was shot dead near Well Petrol Station on the night of August 11 declined to be interviewed out of fear of victimization. In Nyalenda, a family said it could not trace two young men three days after initial protests. In Siaya county, demonstrations also turned violent as police dispersed protesters and carried out search operations in the villages. Evidence given to Human Rights Watch suggests that police killed two young men.

In Siaya county, relatives and two witnesses said that on August 12, police beat to death 17-year-old Kennedy Juma Otieno, after pursuing him from Kisumu’s Busia Road, where they had dispersed protesters with teargas. Human Rights Watch and Kenya National Commission on Human Rights members saw his body in the Sega Mission Hospital Mortuary in Siaya county. His hand, head, and face were swollen.

Relatives and a witness said that police shot and killed Zacchaeus Okoth, a 21-year-old man from Anduro village, Siaya county, on the night of August 11, as the police used teargas and live bullets to disperse crowds of protesters after the announcement of Kenyatta’s victory.

Beatings of Protesters and Residents in Kisumu

On the night Kenyatta was declared the winner, the electricity went off in some parts of Kisumu, plunging residential areas into darkness just as police began door-to-door operations that targeted mainly men for attacks, according to victims of beatings interviewed by Human Rights Watch. At least 100 people were injured by gunshots and beatings.

A police officer in Kisumu said that a combined team of officers from various police units, such as the General Service Unit, Quick Response Team of the Administration Police, Border Patrol, Special Crime Prevention Unit, and Kenya Wildlife Service officers were responsible for the operations. The officers were drawn from several counties and were ferried to Kisumu neighborhoods days before the announcement of presidential results. Plainclothes officers, whom Kisumu residents suspected to be from the directorate of criminal investigations, swarmed the neighborhoods before the demonstrations started.

Multiple witnesses, including those who said they were victims of police beatings in Nyamasaria, Arina, Kondele, Manyatta, and Car Wash neighborhoods, said police responded to the “Uhuru must go” chant with teargas and gunfire. They said police dispersed with teargas any groups of more than three people, even people who were not protesters. International human rights law and Kenya’s constitution guarantee the right of peaceful assembly.

House-to-house operations began soon after the electricity went off. A 32-year-old father of two and resident of Nyalenda said: “Police started throwing teargas in the neighborhood, sometimes even in the houses, and shooting.”

At 11 a.m. on August 12, according to witnesses, police carried out a door-to-door operation in Arina estate, beating men and children and sexually harassing women. A 17-year-old high school student said she was among a group of people the police beat that day for no reason: “I was in the house with my younger brother when police kicked the door open and started beating and stepping on me. They then went to the neighbor where they beat a lady there and her brother.”

Police raided the home of a 35-year-old freelance photographer in Obunga estate and beat him severely: “They broke into my house and started beating me. They were hitting mainly the joints – knee, shoulder, arms, head, and back. They stepped on me for a while and then left me lying there, unable to walk. They broke my rib.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 victims of police beatings and gunshot injuries during the protests and during house-to-house operations in Kisumu alone.

From the hospital records, at least 27 people with injuries were admitted at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (Russia Hospital) on August 11 and 12. On August 17, officials of a makeshift Disaster Management Center told Human Rights Watch that they had registered an additional 92 victims of police beatings and shootings who were yet to seek treatment at any hospital due to fear of reprisal.

Edris Omondi, the head of Disaster Management Center, said: “Some of them have very serious injuries like broken legs, arms and ribs. Others cannot walk or eat at all and they will need urgent medical attention.”

Extortion and Theft from Kisumu Residents

Many witnesses said the police broke into their houses and demanded money or simply stole money and electronic items.

In Arina, a 30-year-old woman said that on August 12, police took Ksh5,000 (US$50) from her and another Ksh2,000 (US$19) from her brother. A 15-year-old girl in Arina said that on the same day police kicked the door to their house open and started beating her with gun butts and batons and stepping on her. The officers took Ksh2,200 (US$21) meant for buying charcoal and food.

In Obunga neighborhood, many families fled the harassment and beatings to seek refuge at Kudho Primary School on the night of August 11. Many said that when they returned home, they found electronics such as radio receivers and television sets and money missing, and presumed that police were responsible.

Those who reported the theft to the nearest police stations in Kondele, Nyamasaria, and Obunga said police were unwilling to investigate and said that thieves had stolen the goods.

“Police are telling us that it was the thieves who stole our items from the houses,” said a mother of three from Nyamasaria. “But which thieves were these when everyone had either run away, was writhing in pain and unable to walk, or dead?”