On the one-year anniversary of the EU plan to relocate 160,000 asylum seekers from Greece and Italy, the first countries of arrival, the scheme must be judged a farce.

First, the EU cut the number by a third. Then, in the year since the plan was approved, it moved just 5,821 people to other member states.

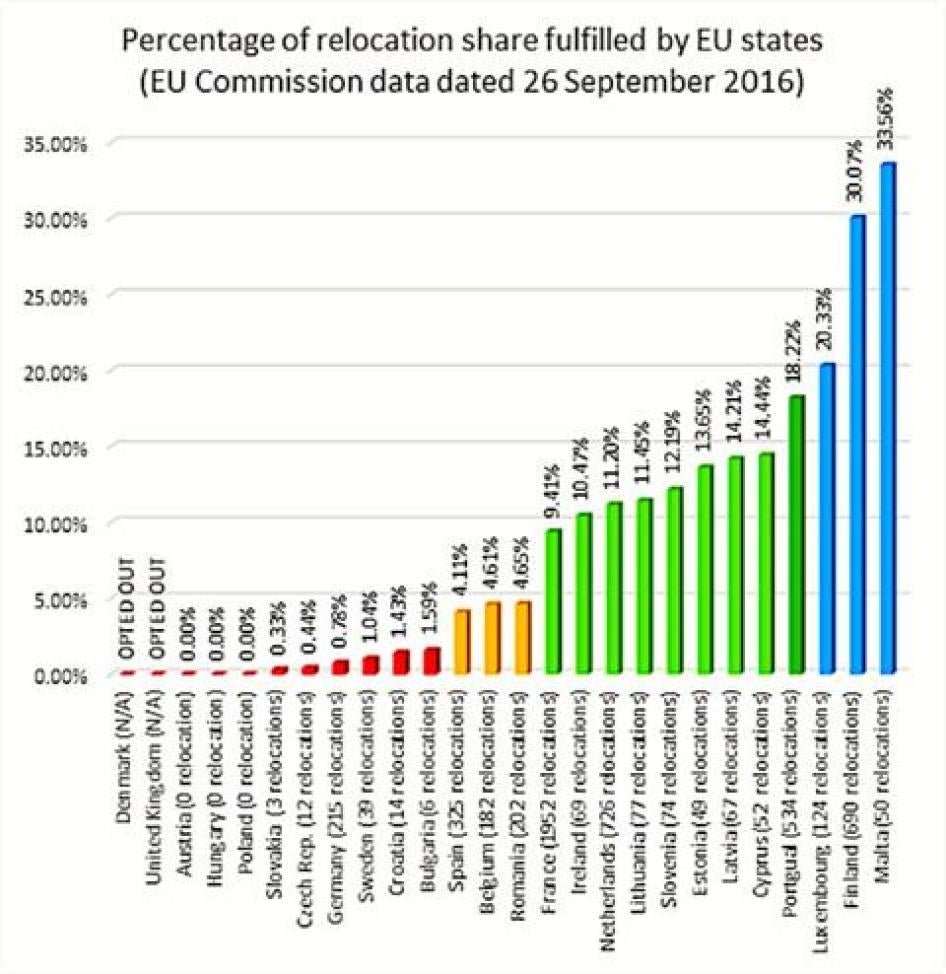

While the relocation requirement is legally binding on EU member states, some countries are flouting EU decision-making rules and shirking their responsibilities.

Some have contributed fairly but others, it would seem, are either actively bucking the programme or passively offering little or nothing in the hope the issue will to go away or that the asylum seekers will end up elsewhere.

Despite an European Commission press statement touting “significant progress” in relocating asylum seekers from Italy and Greece, prime minister Robert Fico of Slovakia said just a few days ago that the idea of migration quotas was “politically finished”.

Indeed, a handful of EU states have aggressively attacked the relocation scheme and the very concept of sharing responsibility.

Last December, Slovakia, which currently holds the EU presidency, and Hungary filed a legal action against the relocation scheme with the EU Court of Justice.

In Hungary, the referendum against the quota has opened the way for a state-sponsored xenophobic anti-migrant campaign. Denmark and the UK took the damaging decision on day one to opt out, while Sweden has successfully sought a one-year delay.

Austria, Hungary and Poland have flatly refused to take anyone. Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia have hardly done better, each taking a dozen or fewer people.

The Visegrad group - the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia - joined by Austria, has proposed no humane alternative and their attacks on the relocation scheme send the grim message to stranded people that their suffering is not a matter of concern.

As for relocating asylum seekers, a disappointingly small group of countries has led by example.

French example

France has relocated the largest number - 1,987 - over a third of the total. Finland, Portugal, the Netherlands and even Malta, Cyprus, and Luxembourg, the EU’s smallest countries, have made progress toward fulfilling their commitments.

Germany, on the other hand, hailed a year ago for welcoming refugees, has been stalling for months. There have been recent positive signs, with over 150 people relocated in just a few weeks. Belgium and Spain, also at the back of the pack, should follow suit.

While a show of solidarity from EU countries is perhaps more important than ever, the crucial goal of the relocation plan is to ensure that asylum seekers are not warehoused in poor conditions and backlogged asylum systems.

Given the human-made tragedy for the over 60,000 asylum seekers stranded in Greece, by that measure too the plan has failed.

Many have been stuck for months in filthy, unsafe camps and with few basic services except for those provided by volunteers. Overcrowding, unacceptable living conditions, lack of protection for women and children, and lack of space in shelters for unaccompanied children are common in Greece and in Italy.

Authorities in both countries are struggling to cope with an increasing number of asylum applications.

As if things weren’t bad enough, many asylum seekers are not even eligible for relocation. Relocation under the plan is open only to nationals of countries whose EU-wide protection rate exceeds 75 percent, based on data updated quarterly.

At the start, Eritrean, Iraqi and Syrian nationals could apply, along with people from a few surprising places like Costa Rica and St Vincent and the Grenadines. But Afghans - one-fourth of those stranded in Greece - were never included. Since June, Iraqis have been ineligible.

In a resolution adopted by a large margin on 15 September, European lawmakers rightly called on the European Council to bring Afghans and Iraqis into the relocation scheme, and urged countries to make at least one-third of their relocation places available by the end of the year.

Lone children

Human Rights Watch believes the EU should consider making unaccompanied children eligible regardless of nationality.

This is an opportunity for the commission to do the right thing: extend the scope of vulnerable asylum seekers eligible for relocation and trigger infringement procedures to hold accountable countries that ignore their obligations.

Member states whose leaders believe in a common European response to the refugee crisis should step up their contribution and oppose the Visegrad group’s obstructionism.

This would bring back some meaningful hope for the tens of thousands of asylum seekers stuck in Greece and Italy.