When I interviewed Akemi, an 18-year-old transgender man, on Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost island, the last place I expected the conversation to lead me was to a comic book store.

“I was born and raised as a female. But even in elementary school, I felt like I wanted to be treated more like a male,” Akemi told me, describing the physical and verbal harassment he faced from as early as his elementary school days and his brutal social isolation in junior high and high school. Though he didn’t have the vocabulary to describe how he felt at the time, he remembers thinking, Is the way I feel wrong?

When he was 16, his sister told him about the word “transgender” and suggested he look it up online. A lot of the websites he found were about medical procedures — but he just wanted information, maybe even a role model. He saw mention of comic books — in Japan’s world-famous manga style — and bought them immediately.

Further north, in Osaka, Aiko, a 20-year-old transgender university student, told me a similar story. When she was 17 and in high school, she happened upon a manga book featuring a transgender character.

“Before reading that comic book, I thought that I was different and I tried to hide it,” she said. “But once I read the comic book I started to think it’s OK to be different and it completely changed how I thought about myself.” But for Aiko the experience was bittersweet — she knew the transgender manga characters, like many of the portrayals of transgender people on Japanese television, were based more on stereotypes than reality.

I was in Japan to document lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth’s experiences of bullying in schools — and, as Human Rights Watch does in 90 countries around the world on a range of issues, produce a report with policy recommendations for the government. In every interview, LGBT students told me that when they began to notice they were different from their peers, they searched desperately for information. Neither Japan’s national school curriculum nor its antibullying policy mentions sexual orientation or gender identity. In this void, LGBT manga characters were both instructive and hopeful.

But they weren’t real people — just storybook characters.

One straight ally who volunteered for an LGBT student group told me, “In high school I started reading comic books. That’s how I came to know about LGBT people. But I thought it only happened in imaginary comic books, not real life.” It wasn’t until years later when a bisexual classmate came out to her that she realized LGBT people were not fictional entertainment devices.

Manga comics and their animated counterpart, anime, are extremely popular in Japan. They’re also safe spaces for creative self-expression, including diverse portrayals of sexual orientation and gender identity. As Japanese activists have noted, while it’s socially acceptable to enjoy gay cartoon characters, it’s less accepted to be openly gay yourself. And while a national debate on same-sex marriage rights has begun in recent years, LGBT people broadly lack basic legal protections.

When LGBT youth are faced with limited information about gender and sexuality, cartoons become a crucial, lifesaving source of information for them as they learn about themselves. As Akemi told me, “I only heard about LGBT people from teachers when they made gay jokes.”

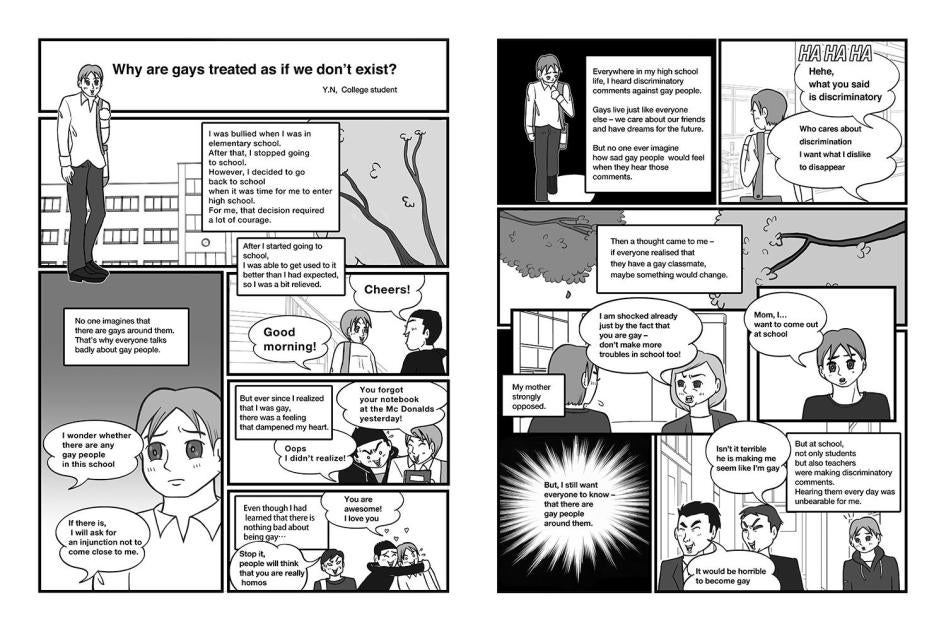

So we wanted to create comic books that reflected the experiences of real people, not fictitious characters. The manga series in our report was produced directly from student testimony we supplied to Taiji Utagawa, a gay cartoonist.

These stories will resonate with a lot of LGBT youth. They should also be instructive for policymakers tasked with making Japan’s schools safe. One is about teacher ignorance, and one about homophobic behavior by teachers. Another is about LGBT students’ feelings of deep isolation, and another about trying to fit in at school.

The voices of Japanese LGBT youth should be included as the government revises both its bullying prevention policy and the national curriculum this year. The four stories Utagawa illustrated for Human Rights Watch offer a glimpse into the barriers LGBT students face. At a very basic level, both documents should acknowledge that there are LGBT students in Japan’s schools — and that they have the same rights as all other students.

KYLE KNIGHT is a researcher in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights program at Human Rights Watch. Follow him on Twitter @knightktm.