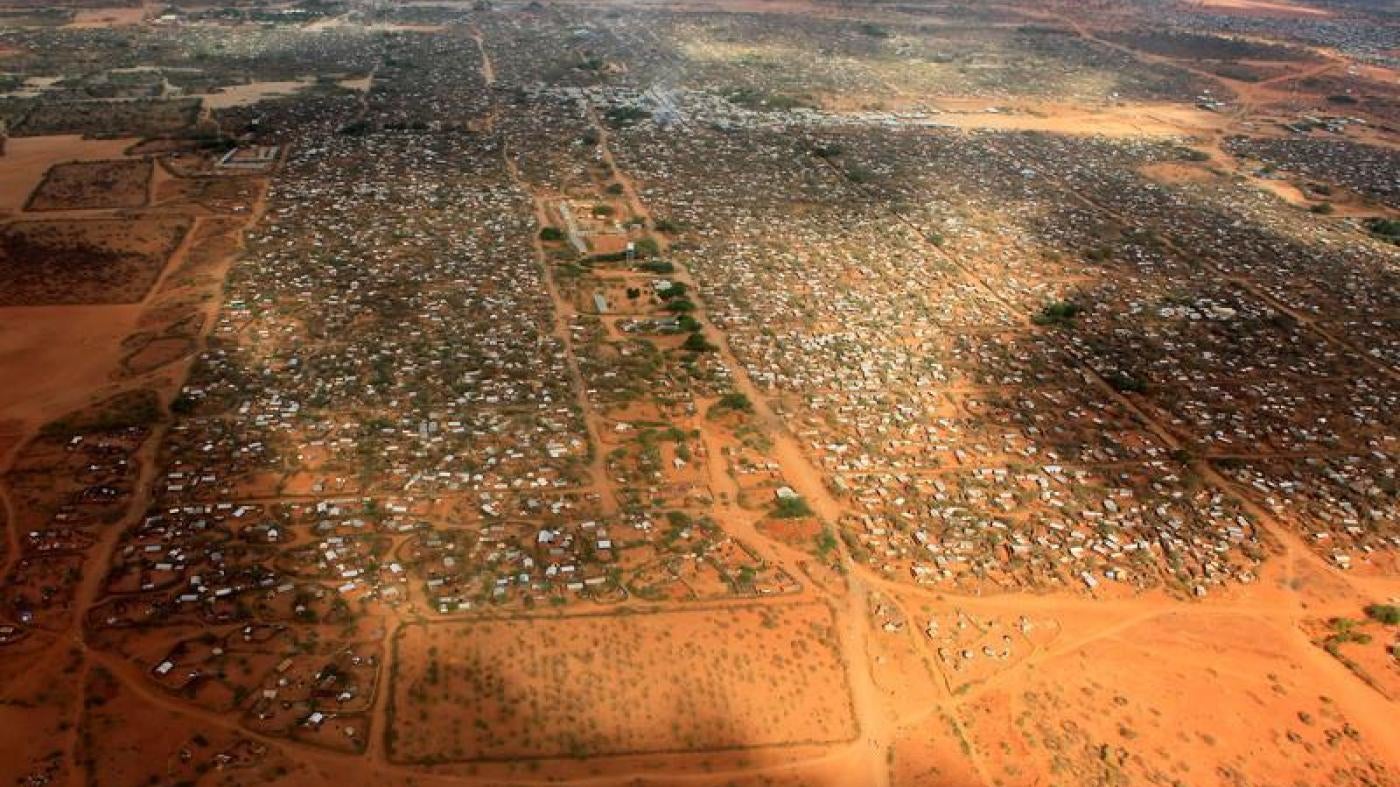

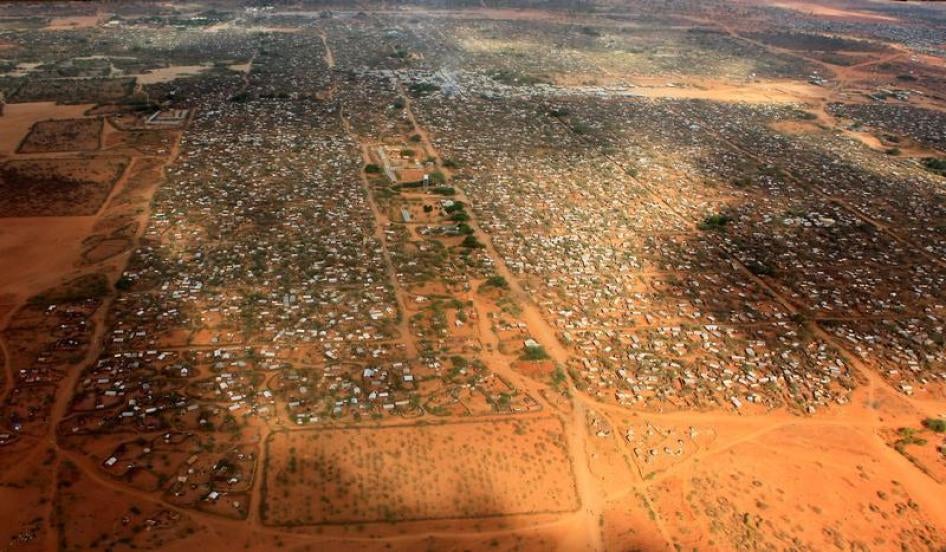

Kenya is home to the world’s largest refugee camp, Dadaab, which provides shelter to 360,000 mostly Somali refugees. In May 2016, Kenya’s government disbanded its department responsible for refugees and announced plans to repatriate Somalis and close Dadaab. Human Rights Watch’s Birgit Schwarz talks with Somalia researcher Laetitia Bader about the difficult and desperate lives of some Somalis in Dadaab, where even food is sometimes scarce, and about why returning them to the dangers of Somalia is simply not an option.

How did Dadaab become the world’s largest refugee camp?

The camp, in the northeastern Kenya desert not far from the Somalia border, was set up in the early 90’s when the Somali state collapsed. It has been a refuge for generations of Somalis fleeing conflict in their own country. Initially they fled fighting between clans, which led to massive displacement and killings of civilians. Over the last 10 years, civilians have primarily been fleeing the repressive and abusive rule of the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab, which continues to control large parts of Somalia, particularly rural areas. Then, five years ago, famine hit Somalia, and a new wave of people arrived in Dadaab, swelling the numbers in the camp further.

At the moment, about 360,000 people live in the camp. The majority are Somalis, but there are also many Ethiopians and South Sudanese who have arrived over the years, seeking refuge from political persecution and conflict.

How well have these refugees been integrated into Kenyan society?

While Kenya has welcomed an enormous number of refugees, the government has been less than willing to integrate these communities. In fact, Kenya has denied refugees their right to free movement. To leave the camp, they needed permission from the Department of Refugee Affairs, which the government just disbanded, claiming that its days of hosting refugees are over. Some of the more established communities have shops and networks of traders who come into the camps. They sell goods or run small cooking places in the camp or spaces where people can come and watch football in the evenings. However, many other camp residents don’t have access to these networks. Those who arrived during the famine in 2011 have virtually nothing and depend on food rations. They cannot leave the camps and can’t seek employment. The rations are their only means of survival.

What struck you the most about the refugees’ plight when you visited the camp in April?

The desperation of these people who fled conflict or hunger and who now feel they may be forced to return to Somalia. Since the World Food Programme cut rations by up to a third for larger households earlier this year, due to limited funding, several families told me they run out of food halfway through the month and some said they have to beg for food. Others are trying to find ways to make a little bit of money on the side by washing clothes for other families in the camp.

This situation is especially difficult for the newcomers, who are not very well-connected in the camps and struggle to even find menial jobs to make up for the ration cuts. They feel caught between a rock and a hard place. Many said: If we are going to die of hunger, we’d rather die at home. But they often lost their goats or their cattle, or had to stop farming because of attacks and harsh taxes by Al-Shabab. They have nothing to start with or to go back to. And they would be going back to areas that the United Nations refugee agency says are dangerous, including places where Al-Shabab is still present or in control.

The Kenyan government seems determined to close the camp and send back the Somali refugees. Is such a move at all feasible and in line with international law?

Any plan that would force Somalis – or other refugees – to return to areas that are not safe would be a serious violation of international refugee law and Kenyan law. We continue to document serious abuses against civilians in many hot spots across south and central Somalia. There are increasing reports of forced recruitment of child soldiers in Al-Shabab-controlled areas. Also, at least 1.1 million people are internally displaced inside Somalia.

There are 350,000 displaced people in unprotected makeshift settlements on the doorstep of the government in Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu. A number of refugees who have returned to Somalia from Dadaab ended up in those horrific camps where they face forced evictions and women and girls are at great risk of sexual violence. Given that situation and the security threat posed by Al-Shabab, this is is not even remotely safe for a large number of people to return there.

Just the trek back to Somalia is very dangerous, with checkpoints manned by armed men all along the way. Some are run by Al-Shabab, some are run by clan militia. At each checkpoint, the returnees face questioning. A number of young men I spoke to and who had recently tried to return to Somalia were questioned about the fact they spoke Kiswahili and had received a “western” education – which the group rejects. They were questioned about what they were wearing, as Al-Shabab imposes a strict dress code on people living in areas under their control. Several said that Al-Shabab had destroyed their smartphones and one boy told me that he was forced to swallow his SIM card because Al-Shabab does not want people in areas under their control to communicate with the outside world. One 20-year-old man who returned with his 15-year-old brother told me they were both picked up at a checkpoint and sent to an Al-Shabab training camp. Fortunately, they were able to escape.

What are the risks for other refugees, beyond Somalis?

Kenya is hosting almost 100,000 South Sudanese who have fled a brutal conflict in which civilians are being attacked and killed, women are being raped, and children are being forcibly recruited as fighters, despite a peace agreement last August. In fact, the attacks on civilians have recently spread to new areas. Ethiopians also try to enter Kenya, fleeing political persecution, as do Burundians fleeing ongoing political violence in their country. And we know that a number of Ethiopian asylum seekers in Kenya who were sent back were mistreated and tortured in detention.

You spoke to quite a few people who made the journey back to Somalia yet ended up returning to Dadaab. Why did these people return to the camp?

Many said that Dadaab, with all its dangers, remains safer than Somalia. Several women who went back said that their children had been traumatized by the sound of gunfire at night. Even in Somali towns under government control, people experience repeated fighting and security incidents. One woman managed to get her clan to buy back her house in Mogadishu for her near the presidential palace, but just a few weeks later the house was destroyed in an attack. She, too, came back to Dadaab. Quite a few young men and boys said that they came back because the fear the risk of recruitment by Al-Shabab.

Access to services like schools and hospitals is also a serious source of concern. In the camp, children at least have access to basic and often free education. The loss of property is another reason. I spoke to an elderly man from Luuq, a town deemed safe by the UN, who returned to Somalia because he has 10 children and his family was particularly affected by the cuts in rations. Back in Somalia, he found his land and house occupied. He went to the authorities to negotiate a return of his property, then spent two months living with his children under a tree waiting for a decision. In the end, he took his family back to Dadaab. There, he said, his children at least did not have to live out in the open and had some basic shelter.

Kenya claims that the camps harbor terrorists. Is there any evidence for this?

The Kenyan government has yet to produce any evidence of Somali refugees being directly involved in any of the Al-Shabab attacks in Kenya. Even if refugees were to be involved, the actions of a few should not be used to punish entire communities or several hundred thousand people. Such discrimination is not only morally and legally heinous, it’s also bad security policy and won’t make Kenya safer. Instead of scapegoating refugees, the government should ensure that there are effective investigations of attacks, leading to the arrest and prosecution of those responsible.

The Kenyan government says that donor countries are not offering sufficient financial support to keep the camp going. Is this true?

The reduction of food rations inside the camp is deeply alarming. International entities have supported the Kenyan government with funding to protect and host these communities in the past, and should continue their support. Furthermore, Kenya’s donors should be pressing Kenya to allow refugees to move freely in and out of camps, to live elsewhere in Kenya, and to sustain themselves by finding work. International groups and other countries should certainly not support sending Somalis back to Somalia against their will. While it is critical for donors and international agencies to provide assistance for refugees inside Kenya, the government should not be using refugees as a bargaining chip to get money.

Given the European Union’s controversial migration deal with Turkey to curb refugee and migration flows to Europe, does it surprise you that Kenya, too, is attempting to rid itself of its refugee problem?

The timing of the Kenyan government’s announcement about closing the camp – just months after the EU agreed to help Turkey in various ways in exchange for reducing the number of Syrian and other refugees moving from Turkey to Europe – does indeed raise questions. While it may not be surprising, it is disappointing. This is a good opportunity for the Kenyan leadership to take the global high ground, show that it upholds basic refugee protection rules – in contrast to some in Europe – and offer assistance to those fleeing violence and persecution.

What else can be done to protect the inhabitants of Dadaab?

There needs to be a formal process to ensure that people who are fleeing persecution and violence, whether in Somalia, Ethiopia, or South Sudan, can claim asylum in Kenya and have their claims processed fairly and in a timely manner. The Kenyan government’s decision to disband the Department of Refugee Affairs means that asylum seekers currently have nowhere to file their claims. And while international support is important for hosting this refugee population, it is also important for Kenya to ensure that Kenyan police don’t return to past tactics to intimidate and terrify the Somali refugee community and that they are not forcing Somalis or other people back to war or persecution.

This interview has been edited and condensed.