(Athens) –Thousands of asylum seekers and migrants at the Athens port of Piraeus face appalling conditions as the crisis for people trapped in Greece due to border closures intensifies, Human Rights Watch said today. The lack of government involvement, poor organization, and scarce resources, as well as lack of information, anxiety, and fear about the new European Union-Turkey deal, are contributing to insecurity and suffering.

“Pregnant women, people with disabilities, and young children in particular are stuck in limbo without dignity or hope,” said Eva Cossé, Greece specialist at Human Rights Watch. “The suffering in Piraeus is a direct consequence of Europe’s failure to respond in a legal and compassionate way to the crisis on its shores.”

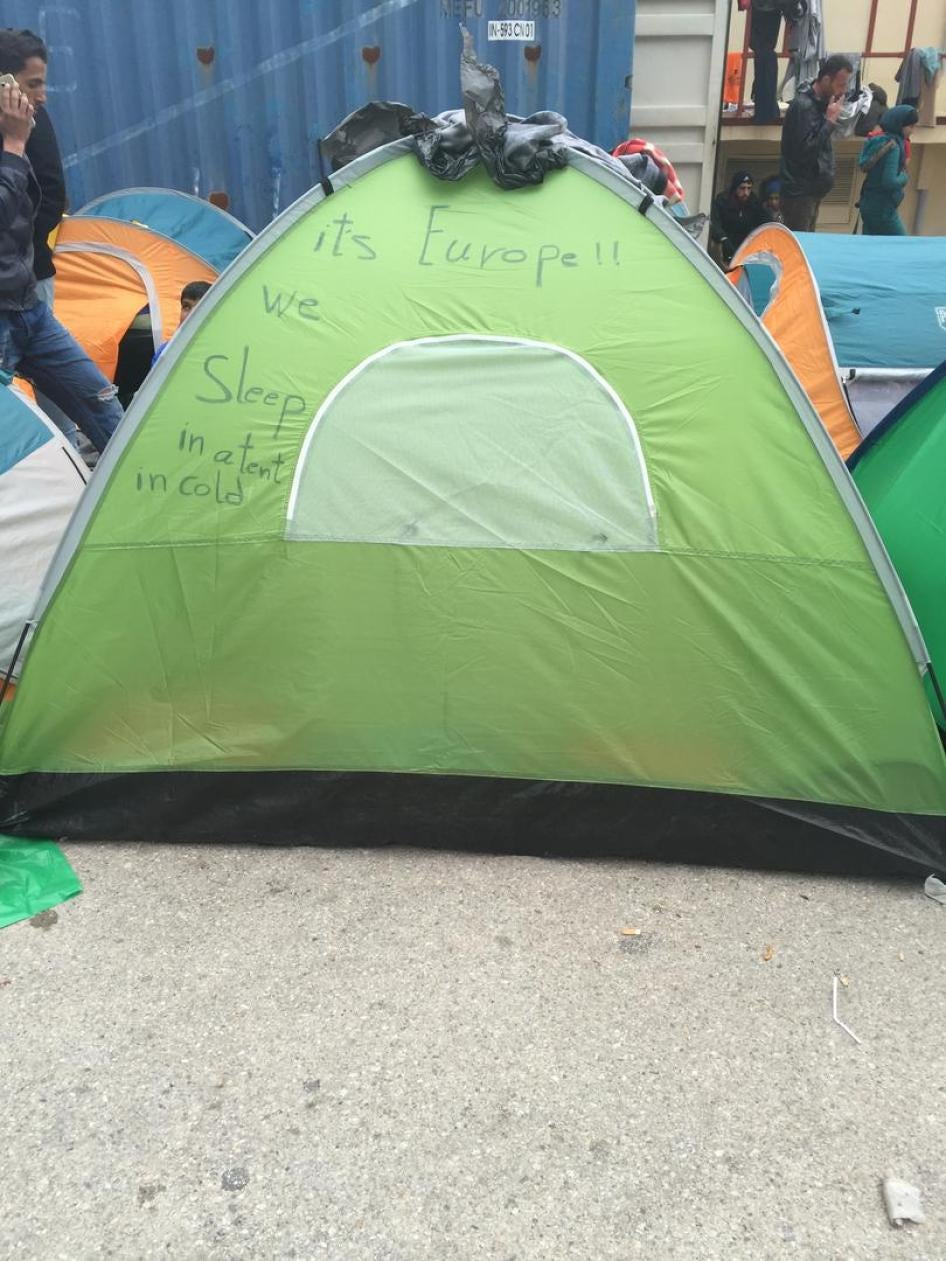

In a visit to Piraeus from March 8 to 22, 2016, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 45 asylum seekers and migrants who had recently arrived at the port from Greek Aegean islands or Greece’s border with the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. An estimated 5,000 women, men, and children are sleeping in squalid, unsanitary, and unsafe conditions in passenger waiting areas, in an old warehouse, in tents outdoors, and even under trucks.

In the absence of any visible government support or personnel, the day-to-day operation of the camps is dependent on volunteers. These volunteers work to coordinate, among other things, the provision of tents, blankets, food, and clothing; identify vulnerable groups; and provide activities for children. For the most part, medical care is provided by aid groups.

From necessity, women and children shelter near unrelated men, exposing the women and children to the risk of sexual harassment and violence, Human Rights Watch said. Three Syrian women interviewed said they sleep with their children wrapped in their arms, terrified kidnappers could prey on them while they sleep. They said they were uncomfortable living with no privacy. Several women said that if they needed to use the toilet at night, their husbands or one of their children accompanied them because they felt unsafe among strangers and unrelated men.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), estimates that women and children, primarily from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, now make up nearly 60 percent of those seeking refuge in Europe.

UNHCR, which had been supporting the Greek authorities in the “hotspots” on the Greek islands, announced on March 22 that it was suspending some of its activities at all closed centers on the islands because “these sites have now become detention facilities.” Hotspots were created under an EU agreement in 2015 to process all arriving asylum seekers and migrants, including to identify those eligible for relocation.

Assurances from the European Commission that relocation of asylum seekers from Greece to other EU member states will be stepped up ring hollow, given poor implementation to date. Despite reforms of the asylum system in Greece in recent years, those who want to apply for asylum in Greece face serious obstacles.

The chaotic situation in Piraeus, combined with people’s fatigue and despair due to the border closures, has created a tense and insecure situation, with several fights breaking out over the past few days over little more than mobile phone chargers or food distribution. Violent confrontations between Syrian and Afghan men broke out on March 18, in which one man sustained light injuries. Police detained two men. In a similar incident on March 17, three men were transferred to an Athens hospital due to injuries. Police and Coast Guard presence is minimal, and volunteers have had to intervene to stop fights. Several women, including women traveling alone, said they felt unsafe because of the fighting. Growing insecurity over the last few days in Piraeus has prompted authorities to increase the police presence.

The EU-Turkey action plan announced on March 18 has contributed to the volatile situation, Human Rights Watch said. The plan, which entered into effect on March 20, foresees mass returns to Turkey of all those who reach Greek islands, on the deeply flawed conclusion that Turkey is a safe country of asylum. Human Rights Watch has criticized the plan, including the dehumanizing proposal to resettle one Syrian already in Turkey for every Syrian returned to Turkey, as a violation of the right to asylum and the prohibition against collective expulsions under EU law.

With no presence of the Greek Asylum Service, nor of any other officials who could provide people with much-needed information about their options in Greece and elsewhere, rumors are creating uncertainty and confusion, Human Rights Watch found. Some people interviewed said they were afraid they would be deported to Turkey if they boarded one of the government-run buses transferring people to official reception camps in an effort to clear the port. Many others had heard that conditions at the government-run camps were not good, prompting them to stay at the port until the “borders open.” Others said they had gone to the camps but found the conditions so bad that they returned to the port.

Greece should mitigate risks for female migrants and asylum seekers, especially those traveling without families and husbands, including providing separate and secure shelter, toilet and shower facilities, and making female staff and interpreters available. They should also ensure that staff are trained to identify signs of gender-based violence and respond to it.

EU countries should move swiftly to fulfill their commitments under the relocation plan to alleviate the burden on Greece, Human Rights Watch said. That should include giving people who arrive in Greece more incentives to participate in the plan through better information and speedier processing, ensuring that individual circumstances such as family ties are taken into account, and making sufficient places available to relocate asylum seekers from Greece and Italy to other EU countries.

Human Rights Watch is concerned by reports that the European Commission intends to propose an amendment to its relocation decision that would use numbers from the relocation plan for the new resettlement scheme that purports to trade one Syrian asylum seeker returned from Greece to Turkey with another refugee to be resettled from Turkey to an EU member state.

“It’s unconscionable that all this suffering and misery at Piraeus port is taking place with the official stamp of EU leaders,” Cossé said. “How long will EU governments turn a blind eye to the human rights violations they are creating.”

Appalling Conditions at the Port

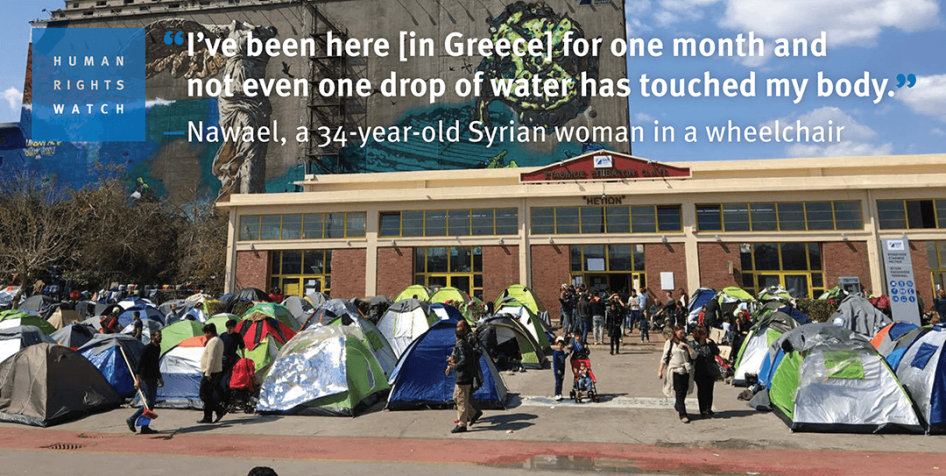

Living conditions in Piraeus, including basic hygiene, are abysmal. Many people sleep outdoors, in tents or on little more than a blanket on the ground, while others sleep inside in overcrowded passenger waiting areas or in an old warehouse. One informal camp has only two showers with only cold water, and others have no showers at all. The small number of toilets, including portable chemical toilets, means they are often dirty and people have to wait in long lines to use them. Accessing basic necessities such as toilets is particularly difficult for people with disabilities. Many people, including numerous women, described to Human Rights Watch not being able to wash for days, or even weeks.

“I’ve been here [in Greece] for one month and not even one drop of water has touched my body,” said Nawael, a 34-year-old Syrian woman in a wheelchair who has been in Piraeus with her husband and three children for more than 10 days. “Here it is very hard for me to go to the toilet. My husband helps me at the door and random women help me inside the toilet. I don’t sleep at night because my body is itchy. My husband helped me and I washed my hair with cold water, but then I got sick. Ten days ago, I got my period and I swear to God, I still haven’t had a shower. And I [usually] pray, but given that I haven’t had a shower [to perform required ablutions], I can’t pray.”

Nawael said that she and her family had registered with the EU’s relocation program 10 days earlier.

With informal camps growing every day in Piraeus, and overwhelmed volunteers effectively running them, Human Rights Watch found that essential needs of women with young children, single mothers, pregnant women, and people with disabilities or health conditions are not being met.

“I’m diabetic, my leg was amputated because of the diabetes,” said Muhammad, a 60-year-old Syrian man in a wheelchair. “All day and all night I’m sitting in my wheelchair.” He said he and his family had registered for the EU’s relocation plan and were hoping to join relatives in Sweden. “If they tell me to go to to Turkey, I’ll go to Syria. I’d rather die in my land. We’re Kurds, we don’t feel safe in Turkey.”

Amina, a 27-year-old Syrian woman traveling with her daughter, 5, and son, 4, said: “Here there is no security. I take my children with me wherever I go. But inside the tent I feel safe. It’s great that [the volunteers] gave us the tent. At least I can change my clothes. And the situation with the toilets is very hard. There’s nowhere to wash.”

Luna, a 30-year-old Syrian woman whose 9-year-old son has intellectual disabilities said: “My son has communication difficulties. He has a disability and can’t be with lots of people. Since we came here, we couldn't believe that the situation is bad like that. They gave us a small tent on the island and the kids sleep inside and we sleep outside. They told me that the Red Cross will help me given my son’s condition, and will make things faster, but no one has come to help us.”

Reception Facilities in Greece

Greek authorities have been opening reception facilities one after the other, but are struggling to find facilities to temporarily host the thousands of people arriving from the islands and at Piraeus.

Many asylum seekers and migrants, including children, are left unassisted, destitute, homeless, or living in substandard conditions. According to UNHCR, Greece had a total reception capacity of 36,910 asylum seekers and migrants as of March 20. But the agency estimates there that more than 50,000 asylum seekers and migrants are on the islands and mainland Greece.

On January 31, the Greek government mobilized the army to assist in setting up centers and hotspots around the country.

Over the weekend of March 19 and 20, the government emptied the hotspots on the islands so it could start implementing the new EU-Turkey plan. According to nongovernmental organizations and the media, about 2,700 people were transferred from Chios island; 4,000 from Lesvos island; and 800 from Samos island. Hundreds were taken to Northern Greece while others arrived to Skaramangas port near Athens. Most will be transferred to military-run camps in mainland Greece.

Human Rights Watch has been unable – despite repeated requests to secure authorization – to visit these reception facilities. Conditions vary, people with knowledge of the facilities have said. An observer with knowledge of the camps told Human Rights Watch: “Some are good, some are atrocious. The camp in Larissa, for example, is army run. There’s one shower for 400 people, five toilets for 400 people, tents with open drains around them full of water. In Lavrio there are wooden houses. There’s a tremendous difference between camps. The army is working around the clock so any new camp will be at basic stages.”

Razia (pseudonum), a young pregnant woman from Afghanistan living in Piraeus with her husband and their 2-year-old son, told Human Rights Watch they had returned to Piraeus from a camp. “One day they came with a bus and took us to a camp but the conditions were horrible. It was raining, the tents had water inside. I was afraid we would get sick.” She said she had gone to the edge of the port the previous night and thought about throwing herself into the sea.

Relocation

Syrians and Iraqis, who together account for 65 percent of arrivals to Greece since the beginning of 2016, are eligible for relocation to other EU member states under a plan agreed upon in 2015. Most of the Syrians and Iraqis Human Rights Watch interviewed had received some kind of information about the relocation plan when they were on the islands. Until recently, European Asylum Support Office (EASO) teams provided information at the port and registered people for the program. Most of those agreeing to participate were transferred to hotels and camps. But volunteers at the port said, and Human Rights Watch confirmed, that EASO teams stopped coming on March 15. An EASO officer had told Human Rights Watch on March 10 that the program was overstretched due to the increasing number of people registering for relocation.

The European Commission recently said it aims to relocate 6,000 asylum seekers a month, but poor implementation to date raises serious concerns, Human Rights Watch said. According to the Greek Asylum Service, as of March 13, the relocation scheme had benefitted only 576 asylum seekers who had arrived in Greece, out of the 1,692 who had registered relocation requests, and EU member states had made only 7,015 places available. Afghans, who make up a quarter of those who have reached Greece by sea so far this year and who have a high rate of recognition for asylum across the EU (79 percent approval rate EU-wide in 2014; 67 percent in 2015) are excluded from the relocation plan.

Under the plan, authorities should take into consideration special needs, family ties, and the best interest of the child in determining destination countries. Yet many women travelling alone with their children told Human Rights Watch they turned down the option of being relocated because their husbands are already in Germany with one or more of their children and they were therefore afraid that the relocation plan would prevent them from joining their other family members.