This summer, as world attention followed every twist and turn of Iran’s nuclear negotiations, within the country a battle for women’s rights played out largely unnoticed by the global media.

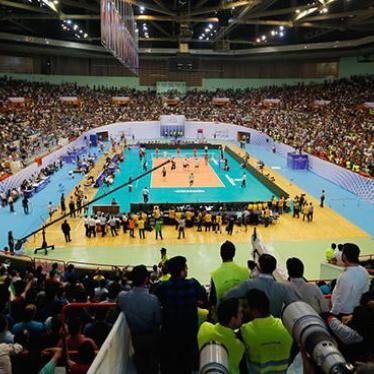

Sports are important to Iranians, but volleyball is a national obsession. Political hardliners and reformists cheer with equal fervor for their winning men’s team. This year, Tehran played host to six World League matches as well as this month’s Asian Volleyball Confederation Championship. In June, Iran defeated the U.S. men’s team twice in historic matches in the capital’s 12,000-seat Azadi (“Freedom”) Stadium.

The Iranian Volleyball Federation is no doubt proud of its men’s team’s achievements. But they should be ashamed of the fact that half of the country’s population was banned from the bleachers. As at all other men’s international volleyball matches held in the country this summer, the authorities barred Iranian women and girls from buying tickets to attend the matches. The regime viewed female fans as so grave a cultural threat, in fact, that they posted police around the stadiums to keep out Iranian women who might try to attend.

Because of volleyball’s popularity and prestige in Iran, the banning of women has become a political football. Indeed, this whole crisis stems from football: a ban on women in soccer stadiums has been in place since the early days of the Islamic Republic, and FIFA, soccer’s governing body, has let this discrimination stand unchallenged for decades. When hardline leaders in Iran saw that FIFA wouldn’t fight for women’s right to attend soccer matches, they extended the ban to volleyball in 2012.

Today, the question of women at volleyball matches has become a flashpoint in the broader struggle for predominance between Iran’s hardliners and reformists. Hardliners are exploiting the coveted hosting rights awarded to Iran by international sport bodies. Last year a female British-Iranian law graduate, Ghoncheh Ghavami, was arrested for trying to watch a men’s volleyball match at the Azadi Stadium. Iran’s Vice-President for Women and Family Affairs, Shahindokht Molaverdi, initially called the ban enforcers “sanctimonious,” but she later backed down under pressure, while vowing to continue efforts to have women and girls admitted as spectators at men’s volleyball competitions.

Enter the FIVB—the Fédération Internationale de Volleyball, which wields immense power over the sport. Like FIFA, it was founded in Paris and is to volleyball what FIFA is to soccer. And like FIFA, the FIVB has repeatedly failed, in the international matches it oversees, to take a stand against Iran’s banning of women spectators.

For more than three years, women in Iran have pressed the FIVB and international sports leaders to defend their rights. Groups of activists share information and try to alert the world to their exclusion via social media, such as @OpenStadiums on Twitter. The Facebook group “Let Iranian Women Enter Their Stadiums” has more than 3,000 followers.

Yet this summer the FIVB allowed all six of its games in Iran to be hosted in stadiums banning Iranian women. Women inside Iran protested to the FIVB and posted photos of the online ticketing system—where only men could buy tickets. The FIVB took no action to ensure women could attend. By failing to speak out against this blatant discrimination, the FIVB flunked a key test of its willingness to enforce its own constitution’s “Fourth Fundamental Principle,” which guarantees non-discrimination. The message to those pushing hardline agendas inside Iran? International sports federations are definitely not prepared to defend women’s most basic rights.

As the final whistle was blown at the Asian Volleyball Championship in Tehran this month, the Asian Volleyball Confederation, which hosted the game and operates under the FIVB umbrella, added its name to the tarnished list of international sports organizations willing to abet gender exclusion.

The irony is that Iran has shown it can be pressured by international sports standards. After the Iranian Revolution, women were kept off the field until the early 1990s when they fought to restart competition with futsal, a form of indoor soccer. Iran’s sports administrators eventually gave in to public pressure and allowed competitions for women’s teams. Today Iran fields many sportswomen and female athletes, including an Iranian women’s soccer team for international competitions, (though women don’t have the resources of men’s teams, and must train on inferior pitches).

At the heart of the matter, keeping women out of stadiums runs counter to sports’ central premise of fair play. Indeed, the International Olympic Committee has identified discrimination as a stain on the movement that they need to clean up resolutely.

Last December, IOC president Thomas Bach passed Agenda 2020, his signature reforms designed to position the Olympics for the modern day. In the wake of the homophobia-ridden Sochi Winter Games, the Olympic Agenda 2020 asserts that discrimination is incompatible with the Olympic Charter and that “gender equality” is a central goal of the Olympic movement. These reforms have—or should have—implications for the IOC’s constituent members, which include both FIFA and the FIVB.

By passing its Olympic Agenda 2020, the IOC has set the ball rolling. But when will the FIVB and FIFA insist that Iran play by the rulebook of international sports and open its stadiums to women?