Summary

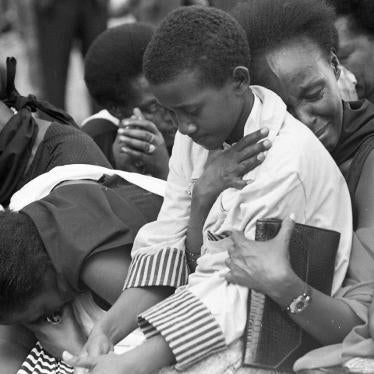

On the 20th anniversary of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, Human Rights Watch stands in solidarity with the victims and with those who survived.

The Rwandan genocide was exceptional in its brutality, in its speed, and in the meticulous organization with which Hutu extremists set out to destroy the Tutsi minority.

Twenty years on, a significant number of perpetrators of the genocide, including former high-level government officials and other key figures behind the massacres, have been brought to justice. The majority have been tried in Rwandan courts. Others have gone before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) or domestic courts in Europe and North America.

Rwanda's community-based gacaca courts finished their work in 2012; the ICTR is expected to complete its own in 2014; and with new momentum for prosecution of Rwandan genocide suspects in foreign countries, the 20th anniversary of the genocide provides an opportune moment to take stock of progress, both at national and international levels, in holding to account those who planned, ordered, and carried out these horrific crimes.

This paper provides an overview of these achievements, focusing on progress made in the area of justice. Recognizing efforts made over the past 20 years to ensure accountability for the crimes committed during the genocide, Human Rights Watch encourages Rwanda and other countries to build on these achievements. The paper also recalls the shameful international failure to prevent the genocide in Rwanda and reflects on the lasting impact of the genocide on the broader Great Lakes region of Africa, with a particular focus on accountability.

I. The Genocide[1]

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying the Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and the Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down over the Rwandan capital, Kigali. The plane crash triggered ethnic killings across Rwanda on an unprecedented scale. Orchestrated by Hutu political and military extremists, the genocide that followed claimed more than half a million lives and destroyed approximately three quarters of Rwanda’s Tutsi population in just three months. Many Hutu who attempted to hide or defend Tutsi and those who opposed the genocide were also targeted and killed.[2] Members of the Rwandan security forces, the notorious interahamwe militia attached to the ruling party, as well as tens of thousands of ordinary Hutu civilians hunted down and slaughtered Tutsi men, women, and children across the country. It was one of the most efficient and terrifying episodes of targeted ethnic violence in recent international history.

In mid-July 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a predominantly Tutsi rebel group based in Uganda, which had been fighting to overthrow the Rwandan government since 1990, defeated the Rwandan army and government. As they took over the country, RPF troops killed thousands of predominantly Hutu civilians, though the scale and nature of these killings were not equivalent or comparable to the genocide.[3] Having secured victory and ended the genocide, the RPF faced the long and arduous process of rebuilding a country that had been almost entirely destroyed.

II. Justice for the Genocide: An Overview of Progress Since 1994

1. Trials in Rwanda: Conventional Courts and Gacaca [4]

Delivering justice for mass atrocities is a daunting challenge in any country, and the scale of the Rwandan genocide would have overwhelmed even the best-equipped judicial system. In Rwanda, the task was made more difficult by the fact that many judges, lawyers, and other judicial staff were killed during the genocide, and much of the country’s infrastructure was destroyed. Despite these challenges, the Rwandan government embarked on an ambitious and unprecedented approach to delivering justice, using both conventional domestic courts and community-based gacaca courts.

Compared with most other countries emerging from mass violence, Rwanda's determination to see justice done and its progress in trying so many alleged perpetrators in less than 20 years have been impressive. But some have paid a high price. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, in particular, thousands of people were arbitrarily arrested, and many were charged and tried in the absence of solid evidence against them. Some might have been wrongly convicted. The lack of safeguards against abusive prosecutions in a weak judicial system heightened the risk of unfair trials.

In 1996, Rwanda adopted a new law governing the prosecution of genocide-related crimes. Genocide trials began in December the same year in a highly charged environment. The legal framework for these prosecutions was established, but the day-to-day demands on the newly reformed justice system were unmanageable.[5] Numerous defendants were convicted without legal assistance as defence lawyers were scarce and often too afraid to defend genocide suspects. The international nongovernmental organization Lawyers without Borders (Avocats sans frontières) provided important assistance through a pool of national and foreign lawyers, but the needs far outweighed their capacity.

The caseload created by the huge number of people who participated in the genocide completely overwhelmed the courts, and the prisons began overflowing. Thousands of prisoners died as a result of extreme overcrowding and life-threatening prison conditions as they waited year after year for their cases to be processed.[6] In 1998, 22 people were publicly executed, many after summary trials and some without legal assistance.[7] These were the only formal executions carried out in connection with genocide trials. Other defendants were sentenced to death after these executions, but their sentences were commuted when Rwanda abolished the death penalty in 2007.

By 1998, the total prison population had reached about 130,000, but only 1,292 people had been tried. It became apparent that it would take decades to prosecute all those suspected of involvement in the genocide.[8]

To overcome this challenge, the Rwandan government devised a novel system for trying genocide cases: gacaca. Gacaca took its name from a community-based dispute resolution mechanism traditionally used to resolve minor disputes, but drew heavily on a more conventional model of punitive justice. Its objectives included not only delivering justice, but also strengthening reconciliation, and revealing the truth about the genocide.

Judges elected by the population, who did not have prior legal training, were to try cases in front of members of the local community, who were expected to speak out about what they knew regarding the defendants' actions during the genocide. As the government developed the gacaca model—a complex and time-consuming task—trials in conventional courts ground to a near halt for almost two years. A gacaca pilot phase began in 2002, but it was not until 2005 that gacaca courts began functioning across the country. Gacaca courts then processed almost two million cases until their closure in June 2012.[9]

In 2011, Human Rights Watch published a detailed report on gacaca based on its field research over nine years.[10] The conclusion was that gacaca left a mixed legacy. Its positive achievements included the courts’ swift work in processing a huge number of cases; the participation of local communities; and the opportunity for some genocide survivors to learn what had happened to their relatives. Gacaca might also have helped some survivors find a way of living peacefully alongside perpetrators. However, many gacaca hearings resulted in unfair trials. There were limitations on the ability of the accused to effectively defend themselves; numerous instances of intimidation and corruption of defence witnesses, judges and other parties; and flawed decision-making due to inadequate training for lay judges who were expected to handle complex cases.[11]

The expectation that gacaca could deliver national-level reconciliation in a matter of a few years, especially so soon after the genocide, was unrealistic from the outset. But gacaca's potential for contributing to reconciliation was hindered by difficulties in revealing the truth, as some participants lied or remained silent due to intimidation, corruption, personal ties, or fear of repercussions. In addition, gacaca did not deliver on its promises of reparations for genocide survivors: survivors received no compensation from the state, and little restitution and often overly formulaic apologies from confessed or convicted perpetrators—casting doubt on the sincerity of some of these confessions. While gacaca may have served as a first step to help some Rwandans on the long path to reconciliation, it did not manage to dispel distrust between many perpetrators and survivors of the genocide.

In addition to the large number of people tried by gacaca courts, to date at least 10,000 people have been tried for genocide-related crimes by the conventional courts,[12] the majority before gacaca started, others while gacaca was ongoing,[13] and some since it closed in 2012.

The standard of genocide trials in Rwanda's conventional courts has varied enormously. Some, particularly in the early post-genocide period, were marred by a failure to respect due process, pressure on judges, intimidation of witnesses, interference by outside parties and, in some cases, by the government. Others, especially in more recent years, have shown greater respect for due process, partly thanks to extensive legal and institutional reforms and enhanced training and professionalization of judicial staff.[14] The release of tens of thousands of prisoners over the last 10 years has also significantly improved prison conditions.

2. Trials at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)

In response to the genocide, the United Nations Security Council set up the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 1994, with a mandate to prosecute “persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda and Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring states between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994.”[15] At time of writing, the ICTR had tried 75 individuals in 55 cases; 49 individuals were convicted; 14 were acquitted; 12 were awaiting the outcome of appeals. The ICTR is currently winding down its operations and all proceedings are expected to conclude by the end of 2014, with the exception of one case in which the appeal is due to conclude in mid-2015.[16]

The ICTR was only ever expected to try a small number of suspects: primarily those who played a leading role in the genocide. To some extent, it has performed this task, and has tried and convicted several prominent figures, including former Prime Minister Jean Kambanda, former army Chief of Staff General Augustin Bizimungu, and former Ministry of Defence Chief of Staff Colonel Théoneste Bagosora. The ICTR also set important precedents in the development of international criminal law, such as the first-ever prosecution of rape as genocide in the case of a former bourgmestre (mayor), Jean-Paul Akayesu. However, the tribunal has inherent limitations, as is the case with most international tribunals, and attracted criticism, particularly by Rwandans, for the relatively small number of cases it has handled, its high running cost, bureaucratic processes, the length of time trials have taken, and the fact that it was located outside Rwanda.

Perhaps the most significant failure of the ICTR has been its unwillingness to prosecute crimes committed by the RPF in 1994, many of which constituted war crimes and crimes against humanity. Although the ICTR had a clear mandate to prosecute these crimes (its jurisdiction covers genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity), not a single RPF case has been brought before the ICTR for prosecution, creating a sentiment among some Rwandans and international legal observers that it provided only victor’s justice. Pressure from the Rwandan government, combined with a reluctance to offend the government and jeopardize its cooperation with the ICTR, resulted in the ICTR focusing exclusively on genocide-related crimes. Relations between the government and the ICTR came to a head in 2002, when, in response to indications that the ICTR may have been planning to pursue investigations into RPF crimes, the Rwandan government refused to cooperate with the ICTR by facilitating the travel of witnesses from Rwanda and providing access to documents. These obstacles were later lifted, but relations between the government and the ICTR have remained cool. The government continues to criticize aspects of the ICTR's performance, particularly when the tribunal has acquitted defendants or reduced their sentences on appeal.[17]

In a further demonstration of the ICTR’s unwillingness to handle these politically sensitive cases, in 2008 ICTR Prosecutor Hassan Jallow transferred the case of four RPF officers accused of killing 15 civilians in 1994 to the Rwandan national court system, for prosecution inside the country. Human Rights Watch monitored the trial and concluded that it was a political whitewash (see “Justice for RPF crimes” below).[18]

ICTR Transfers to Rwanda

Since 2011, the ICTR has transferred several genocide cases to the Rwandan courts. The first was that of Jean Bosco Uwinkindi, who was sent to Rwanda in April 2012. Preliminary proceedings in his trial, as well as in the trial of Bernard Munyagishali who was sent to Rwanda in July 2013, have begun in the High Court in Kigali. The ICTR has also agreed to transfer several other cases to Rwanda, including those of six indicted individuals who are still at large.

These decisions have been controversial. In order to obtain the transfer of cases from the ICTR, as well as extraditions of genocide suspects from other countries (see below), the Rwandan government has undertaken a number of legislative reforms aimed at meeting international fair trial standards. Some of these have been important and positive, for example the abolition of the death penalty in 2007 and the creation of a witness protection unit. Nevertheless, ICTR judges turned down several earlier requests by the ICTR prosecutor to transfer cases to Rwanda, notably in 2008, as they did not consider that the Rwandan judiciary could guarantee a fair trial. In the face of this refusal, the Rwandan government introduced additional reforms, which eventually paved the way for the ICTR to agree to transfer cases to Rwanda for domestic prosecution.

Human Rights Watch has documented major legal reforms in Rwanda in the last few years, but maintains the view, on the basis of its own trial observations and research in Rwanda, that the Rwandan justice system still lacks sufficient guarantees of independence and that fair trials cannot be guaranteed in all cases. Although Human Rights Watch and other organizations brought these concerns to the attention of the ICTR, most recently in 2011, the tribunal ruled that it was safe to transfer these cases to the Rwandan courts on the basis that legislative reforms in Rwanda had addressed some of its earlier concerns.

3. Trials in Foreign Countries and Extraditions to Rwanda

Many Rwandans fled their country during and after the genocide in 1994 and sought asylum in various countries in Africa, Europe, North America, and elsewhere. Among those claiming to be refugees were individuals suspected of having participated in the genocide.

Over the past 20 years, national authorities in some of the countries where Rwandan genocide suspects are living have conducted investigations into these individuals’ alleged involvement in genocide-related crimes, leading to a number of trials before the domestic courts of these countries, under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Universal jurisdiction refers to the ability of national courts to try people suspected of serious international crimes, such as genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, or torture, even if neither the suspect nor the victim is a national of the country where the court is located and the crimes took place outside that country.

Trials of Rwandan genocide suspects have taken place in several countries including Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Canada, Finland, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, and France. Dozens of criminal investigations are ongoing against other Rwandan genocide suspects in these and other countries. In some cases, for example in the United States, Rwandan genocide suspects were charged and tried on immigration-related offenses for concealing their alleged role during the genocide.

In some of these countries, many years elapsed before trials began. For example, in France, a country to which a number of known genocide suspects had fled after the genocide, it was not until February 2014 that the first Rwandan genocide suspect—Pascal Simbikangwa, a former intelligence chief under the Habyarimana government—was tried. This was the first case brought to trial by a newly created war crimes unit in France. It was a significant moment, as France had backed the former government of Rwanda and supported and trained some of the forces which went on to commit genocide. On March 14, 2014, a court in Paris found Simbikangwa guilty of genocide and complicity in crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 25 years in prison. Just one month earlier, on February 18, 2014, a court in Germany delivered a guilty verdict in the case of former mayor Onesphore Rwabukombe and sentenced him to 14 years’ imprisonment for aiding and abetting genocide. These cases are important milestones in the demonstration of international commitment to ensuring that perpetrators of the genocide are held accountable, wherever they are found.

Extraditions

Until the first ICTR transfer decision, most countries denied extradition requests from Rwanda. Over the last few years, however, governments have increasingly tended to seek the extradition of genocide suspects to Rwanda to face trial there, rather than prosecute them in their own courts. Following the ICTR decision to transfer its first genocide case (Uwinkindi) to Rwanda in 2011, courts in several countries, including Sweden and Norway, followed suit and agreed to extraditions. A ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in October 2011 that it was safe to extradite Sylvère Ahorugeze, a Rwandan genocide suspect arrested in Sweden, reinforced this trend.[19] Prosecutors and judges in extradition cases in various countries have cited the ICTR and ECHR decisions as precedents when arguing in favor of extradition.

Extradition proceedings and appeals are currently ongoing in several countries, including in the case of five Rwandans in the United Kingdom. Four of them had previously faced the prospect of extradition in 2009, but the High Court of Justice had concluded that they should not be sent back to Rwanda because of the real risk of a flagrant denial of justice.[20] Fresh extradition hearings are proceeding in this case at time of writing.

One of the most prominent Rwandans to be extradited is Léon Mugesera, a former academic and government official accused of publicly inciting ethnic hatred and violence against Tutsi in the period leading up to the genocide. A resident in Canada for many years, Mugesera was extradited to Rwanda in January 2012. His trial at the High Court in Kigali began in February 2012 and is ongoing at time of writing. Mugesera faces several charges, including planning of and public incitement to genocide. The trial has been complex, with Mugesera appearing to deliberately prolong some of the initial stages, claiming he needed more time to prepare his defense. 16 out of 28 prosecution witnesses have been heard so far.[21]

In principle, Human Rights Watch agrees that it is best for grave international crimes such as genocide and crimes against humanity to be prosecuted where they were committed, close to the victims and the affected population. However, in the case of countries such as Rwanda where the justice system still lacks full independence and the government can influence the outcome of trials, especially in politically sensitive cases, Human Rights Watch has concerns about the opportunity for suspects to receive a fair trial in domestic courts.

III. Justice for RPF Crimes

In contrast to progress in trying perpetrators of the genocide, very few RPF members have been held to account for the war crimes and crimes against humanity they committed in 1994. These killings were not in any way equivalent to the genocide, but the victims and their families have a right to see justice done. Human Rights Watch believes that the impunity protecting most RPF members from prosecution for these crimes has not only led to a sense that the RPF is above the law, but may have hindered progress toward reconciliation in the aftermath of the genocide.

After the genocide, the new government formed by the RPF admitted that its troops had carried out killings in 1994, but sought to downplay these crimes, describing them as isolated cases of revenge and claiming that it was bringing those responsible to justice. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, fewer than 40 RPF soldiers have been tried for these crimes, and most have received comparatively lenient sentences.[22] They include four officers charged with war crimes in connection with the murder of 15 civilians, including 13 clergy and a young boy, in 1994. In a case initially prepared by the ICTR then handed over to Rwanda by the ICTR prosecutor, a Rwandan military court in 2008 acquitted the two most senior officers and sentenced the two lower-ranking ones, who confessed to the killings, to eight years’ imprisonment; their sentences were reduced to five years on appeal in 2009.[23]

Under the original 2001 gacaca law, gacaca courts had jurisdiction over war crimes as well as genocide and crimes against humanity, so they could conceivably have handled cases of RPF crimes from 1994. However, the reference to war crimes was removed from the law in 2004 and the government let it be known publicly and unambiguously that gacaca would not cover RPF crimes.[24]

For the vast majority of families of victims of RPF killings, there is therefore little hope of seeing the perpetrators prosecuted. A few have attempted to demand justice for these crimes, but it has been a difficult struggle. There are tight restrictions on free speech in Rwanda, and few people dare broach publicly the sensitive subject of RPF crimes. Talking about those crimes, and effectively departing from the official version of Rwanda's recent history, can carry serious consequences, such as charges of genocide denial, genocide ideology or divisionism (inciting ethnic divisions). Rwanda has passed a number of laws which may originally have been intended to prevent and punish hate speech of the kind which led to the 1994 genocide, but in practice, have restricted free speech and imposed strict limits on how people can talk about the genocide and other events of 1994.[25]

IV. Accountability for the Aftermath of the Genocide in the Great Lakes Region

The Rwandan genocide has had a lasting impact on some of Rwanda's neighbors, particularly Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where its consequences are still felt today.

Burundi

Rwanda’s genocide was inextricably linked with events in neighboring Burundi, a country with a similar ethnic make-up to Rwanda and a parallel, extremely bloody history. Not only was Burundi's president, Cyprien Ntaryamira, killed at the same time as Rwanda's president Habyarimana on April 6, 1994, but six months earlier, on October 21, 1993, Burundi’s first Hutu democratically-elected president, Melchior Ndadaye, was also assassinated. Ndadaye's assassination unleashed a wave of ethnic massacres in Burundi in which tens of thousands of Tutsi and Hutu were killed in late 1993 and early 1994.

The violence in Burundi directly fuelled tensions in Rwanda, and the weak international reaction to these massacres may have emboldened Hutu extremists in Rwanda to proceed with their genocidal plans.[26] In Burundi too, events in Rwanda deepened ethnic divisions and fear: Hutu and Tutsi watched in shock as the genocide unfolded just across the border. Remarkably, ethnic violence in Burundi has practically ceased in recent years, but has been replaced by political violence.

On the international level, the genocide in Rwanda eclipsed events in Burundi, but the killings and other widespread ethnic violence in Burundi continued long after the Rwandan genocide had ended, developing into a protracted armed conflict that lasted many years.[27] There has been little accountability for most of the crimes committed in Burundi in the 1990s. Some Hutu and Tutsi were arrested and detained in connection with the violence, but most of those responsible for ordering the killings at a higher level, on both sides, have not been held accountable. The Burundian government has repeatedly promised to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to cover past crimes, but by early 2014, the draft law establishing the commission has still not been adopted.

Democratic Republic of Congo

The consequences of the Rwandan genocide on neighbouring Congo have been devastating. Since 1996, the east of the country, in particular, has been torn apart by repeated cycles of violence and abuse.[28]

As the RPF defeated the genocidal forces in 1994, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans, most of them Hutu, fled en masse from the advancing RPF troops. Many settled in huge refugee camps in the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaïre), while others fled to Tanzania and Burundi. The refugees were accompanied by people who had participated in the genocide, including members of the former government, army and interahamwe militia, who established control over some of the refugee camps. Little was done by the then Zairian government or United Nations agencies to demilitarize the camps which Hutu extremists used as bases for preparing attacks on Rwanda and pursuing anti-Tutsi propaganda campaigns.

In November 1996, the new Rwandan army formed by the RPF, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), backed by Uganda, invaded Congo to destroy the refugee camps, and, together with a hastily constituted Congolese rebel group, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaïre (Alliance des forces démocratiques pour la libération du Congo-Zaïre, AFDL), overthrew the country’s president, Mobutu Sese Seko, who had backed the Rwandan Hutu extremists. The attacks on the refugee camps killed thousands and forced the return to Rwanda of many of the surviving Hutu refugees. Many were arrested on their return to Rwanda on accusations of genocide; others were among thousands killed by the RPA in counter-insurgency operations in northwestern Rwanda in the late 1990s.[29] Those refugees who did not return to Rwanda, including large numbers who had not been involved in the genocide, fled deep into the forests of Congo, where Rwandan and AFDL troops massacred tens of thousands of them.

Today, Congo remains unstable, and violence continues in the east. One reason is that some members of the former Rwandan army,interahamwe militia, and other individuals suspected of having participated in the genocide formed an armed group in eastern Congo. After using a succession of different names, this group became known as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda, FDLR). Many members of the FDLR today are too young to have participated in the genocide in Rwanda; however, their leaders and combatants still include some individuals believed to have participated in the genocide.

The FDLR, still predominantly a Rwandan Hutu armed group, conducted sporadic attacks in Rwanda after the genocide, but these have almost ceased in more recent years as the FDLR has become significantly weakened. However, the FDLR continues to commit horrific violence against Congolese civilians, sometimes in alliance with Congolese armed groups.[30] Some of its members have returned to Rwanda through an official disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration process, overseen by the UN, but others have resisted return and continue to keep thousands of Rwandan refugees hostage in Congo.[31]

There has been some progress in prosecuting FDLR leaders for crimes committed in Congo. In November 2009, two FDLR leaders, Ignace Murwanashyaka and Straton Musoni, were arrested in Germany on charges of belonging to a terrorist organization and bearing command responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Congo. Their trial began in May 2011 and is ongoing at the time of writing.[32] Several other FDLR members have been indicted by a German court for membership of a terrorist organization engaging in war crimes and crimes against humanity. Investigations are ongoing in other countries.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has indicted two FDLR leaders for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Congo. The first, FDLR Executive Secretary Callixte Mbarushimana, was arrested in France in October 2010 on the basis of an ICC arrest warrant, but pre-trial judges declined to confirm the charges against him for lack of sufficient evidence, and he was released from the court’s custody in December 2011.[33] Mbarushimana is also under investigation by a French war crimes unit in relation to crimes allegedly committed during the genocide in Rwanda. The second, Sylvestre Mudacumura, military commander of the FDLR, was indicted by the ICC in May 2012; he remains at large in Congo at the time of writing.[34]

V. The Legacy of International Responses to the Rwandan Genocide

Despite repeated warnings by Rwandan and international human rights organizations, diplomats, UN staff and others that a genocide was being prepared,[35] governments and intergovernmental bodies, including the United Nations and the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), dramatically failed to act to prevent the genocide as it unfolded in 1994. The UN peacekeeping force that was present in Rwanda withdrew most of its troops at the height of the massacres, leaving the Rwandan civilian population without defense or protection.[36] Given that many of the killings during the genocide were carried out by civilians using machetes and clubs, rather than by military using firearms, UN peacekeepers could have saved many lives by intervening at an early stage—all the more so if their numbers had been increased and their mandate strengthened. Instead, most of the peacekeepers withdrew, giving free rein to the genocidal killers.[37]

French troops eventually intervened in June, two months into the genocide, with UN Security Council authorization. France's intervention, known as Opération Turquoise, was problematic, as the French government had long supported the government of President Habyarimana and continued supporting the interim government during the genocide. Many observers condemned its intervention as an attempt by France to save its former allies from defeat and slaughter by the RPF. However, Opération Turquoise did also succeed in saving some Tutsi during the last month of the genocide.[38]

In the following months and years, as the horror of the Rwandan genocide sank in, “never again” became a common refrain. A number of world leaders acknowledged, and some apologized for, their failure to halt the genocide in Rwanda. They included former US president Bill Clinton, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan (who was Under-Secretary General for Peacekeeping at the time of the Rwandan genocide), and former Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt.[39]

Overwhelming guilt at their individual and collective failure to stop the genocide has been a defining factor in many governments’ foreign policy towards Rwanda since that time. Twenty years on, it continues to color international perceptions of and reactions to events in Rwanda and in the Great Lakes region, especially in relation to the human rights situation in present-day Rwanda and Rwanda’s repeated incursions into Congo.

In terms of justice, the genocide in Rwanda, together with the wars in the Balkans, marked a turning point in international commitment to including accountability and criminal trials as part of responses to grave crimes under international law. The creation of the ICTR in 1994, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia the year before, paved the way for international justice. One important and direct legacy of the genocide in Rwanda was the creation of the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) in 1998. Today, there is a fledgling system of international justice with a “court of last resort” that is tasked with limiting the repetition of horrors of the kind Rwanda experienced in 1994 and trying perpetrators where the national courts are unable or unwilling to do so. The ICC is the first permanent international criminal court whose mandate is not limited to a specific situation but which has broad jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. The ICC currently has 120 state parties and is investigating grave international crimes in eight countries.

Although international justice mechanisms have contributed to addressing some of the crimes committed during the Rwandan genocide, the Rwandan government has been very critical of the ICC. Rwanda, which is not a member of the ICC, has complained that the court has disproportionately targeted African countries and described the ICC as a tool of Western powers against developing nations.[40] In its nearly 18 months as an elected member of the UN Security Council, Rwanda has consistently opposed references to the ICC in thematic resolutions and statements.

VI. Conclusion

As the world’s eyes turn to Rwanda once again 20 years after the genocide, political leaders, media and other observers will be reflecting on the horrific crimes committed in 1994 and on the shocking international failure to prevent them.

Twenty years on, significant progress has been achieved in bringing some of the perpetrators to justice, both nationally and internationally. The combination of national and international action to end impunity for the genocide in Rwanda has also marked a turning point in the development of justice for international crimes more broadly.

Human Rights Watch encourages the Rwandan government and other governments around the world to pursue efforts to arrest and prosecute—in fair and credible trials—other perpetrators who are still at large.

The Rwandan authorities should also bring to justice RPF members responsible for carrying out or ordering war crimes or crimes against humanity in 1994, and ensure that families of the victims of these crimes, as well as witnesses, are able to speak freely about these events without fear for their security.

Finally, Human Rights Watch encourages the Rwandan government to pursue its reforms of the justice system with a view to further strengthening its independence, and to enable those who suffered serious miscarriages of justice—whether defendants or survivors of the genocide—to seek a review of their cases within a reasonable period. This would not only provide an opportunity for redressing these errors, but demonstrate deeper commitment to delivering fair and credible justice for the genocide. It would also serve as an example to other countries in the region in terms of enforcing accountability for grave crimes.

The Work of Human Rights Watch in RwandaHuman Rights Watch has been documenting and exposing human rights violations in Rwanda since the early 1990s. Its senior advisor in the Africa Division, Alison Des Forges, one of the world’s foremost experts on Rwanda, dedicated her life to the struggle for human rights in the Great Lakes region of Africa, and to Rwanda in particular. In the period leading up to the genocide, she worked tirelessly to alert world powers to the impending crisis in Rwanda. Few would listen. By the time the genocidal forces had unleashed their sinister program and the world had woken up to the full horror that was unfolding in Rwanda, it was too late. Alison Des Forges’s efforts did not stop when the genocide ended. She continued painstakingly gathering information on the killings, rapes and other horrific crimes, which she compiled into what has become one of the main reference books on the Rwandan genocide: “Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda”, an 800-page account of the genocide and of the events which preceded and succeeded it, published jointly by Human Rights Watch and the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) in 1999. Alison Des Forges also testified as an expert witness in 11 trials at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania, as well as in domestic court proceedings involving Rwandan genocide suspects in several countries. Alison Des Forges campaigned vigorously for justice for the genocide until her sudden death in a plane crash in the US on February 12, 2009. She also documented human rights abuses by the new government of Rwanda after the genocide and advocated for accountability for all abuses, past and present. Her death left a huge void in Rwanda and in the broader community of human rights activists, academics and friends of Rwanda. Human Rights Watch has had a researcher and a small office in Rwanda since 1995. Initially, documentation of the genocide was one of the main tasks of the office, but there were also pressing, new human rights concerns in Rwanda: in the aftermath of the genocide, the government formed by the RPF was itself responsible for numerous abuses, some of which persist in Rwanda today. Over the last 20 years, Rwanda has made huge strides in rebuilding the institutions and the infrastructure that were destroyed during the genocide, in delivering public services and in expanding its economy. As noted in this paper, there have also been significant improvements in the functioning of the justice system and in prison conditions. But these improvements have not been matched by progress in respect for civil and political rights: the government has imposed severe restrictions on freedom of expression and association and strongly resisted moves towards democracy. Human Rights Watch continues to document these and other concerns in Rwanda today.[41] Trial observation and advocacy for legal reform also remain a central part of the organization's work in the country. |

[1]For a detailed description of the Rwandan genocide, see Human Rights Watch/International Federation of Human Rights, Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1999), https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story. For additional information on how the genocide was planned, see Human Rights Watch, Rwanda: Documents Shed New Light on Genocide Planning, April 7, 2006, https://www.hrw.org/news/2006/04/07/rwanda-documents-shed-new-light-genocide-planning.

[2]Various figures have been advanced as to the total number of victims of the genocide, ranging from 500,000 to more than one million. The exact number of victims may never be known. The Rwandan government website refers to more than one million Tutsi killed: “Brief History of Rwanda,” Government of Rwanda, http://www.gov.rw/History (accessed March 2014). The government’s National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide states that over 80% of the Tutsi population were killed: “Genocide”, National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide, http://www.cnlg.gov.rw/genocide-28.html (accessed March 2014).

[3]For details of crimes committed by the RPF in 1994, see Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 692-735, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story. The UN estimated that between 25,000 and 45,000 people were killed by RPF soldiers between April and August 1994.

[4]The findings and analysis in this paper are based on Human Rights Watch field research and trial observation in Rwanda since the end of the genocide. Some of these findings are described in more detail in earlier Human Rights Watch publications, in particular, Law and Reality: Progress in Judicial Reform in Rwanda, July 26, 2008, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/25/law-and-reality, and Justice Compromised: the Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts, May 31, 2011, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/05/31/justice-compromised-0.

[5]For details of the legal basis for genocide prosecutions and the challenges facing the new Rwandan government after the genocide, see Human Rights Watch, Law and Reality: Progress in Judicial Reform in Rwanda, July 26, 2008, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/25/law-and-reality.

[6]See Human Rights Watch, Justice Compromised: the Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/05/31/justice-compromised-0, and Amnesty International, “Rwanda: the troubled course of justice”, AI Index: AFR 47/010/2000, April 25, 2000, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AFR47/010/2000/en(accessed March 2014).

[7]See Human Rights Watch/International Federation of Human Rights, “Human Rights Watch and the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues (FIDH) Condemn Planned Execution of 23 in Rwanda,” April 23, 1998, https://www.hrw.org/news/1998/04/23/hrw-and-fidh-condemn-planned-execution-23-rwanda, and Amnesty International, “Major Step Back for Human Rights as Rwanda Stages 22 Public Executions,” April 24, 1998, http://www-secure.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AFR47/014/1998/en(accessed March 2014).

[8]See Human Rights Watch, Law and Reality: Progress in Judicial Reform in Rwanda, July 26, 2008, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/25/law-and-reality.

[9]A report by the National Service of Gacaca Courts, published in June 2012, states that gacaca courts tried 1,958,634 cases of genocide. The report also provides details of the structure and functioning of gacaca courts. See National Service of Gacaca Courts, Gacaca courts in Rwanda, Kigali, June 2012, http://www.minijust.gov.rw/uploads/media/GACACA_COURTS_IN_RWANDA.pdf (accessed March 2014).

[10]Human Rights Watch, Justice Compromised: the Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/05/31/justice-compromised-0 and Human Rights Watch, Rwanda: Case Studies, https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/06/03/rwanda-case-studies.

[11]Ibid.

[12]This is an approximate total based on data from Rwandan government sources, including the Supreme Court annual reports, and non-governmental sources. The real number may be higher, as some statistics refer to the number of individuals tried, while others refer to the number of cases, some of which may cover several individuals.

[13]The law governing the prosecution of genocide crimes classified genocide suspects into four groups, later reduced to three: Category 1 included those responsible for leading and instigating the genocide, well-known killers, and rapists; Category 2 included those responsible for killings and serious assaults; and Category 3 covered those responsible for stealing, destroying or damaging property. Until June 2008, Category 1 suspects continued to be tried by the conventional courts, not by gacaca courts. From June 2008, most of these cases too were transferred to the gacaca system.

[14]Human Rights Watch, observation of genocide trials in Rwanda, 1997 to 2014. For details of some of the legal reforms, see Human Rights Watch,Law and Reality: Progress in Judicial Reform in Rwanda, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/25/law-and-reality. Further reforms have taken place since 2008, and new laws have been adopted, notably a revised law on genocide ideology passed in 2013.

[15]United Nations Security Council, Resolution 955 (1994), S/RES/955 (1994), November 8, 1994, http://www.unictr.org/Portals/0/English%5CLegal%5CResolutions%5CEnglish%5C955e.pdf (accessed March 2014).

[16]For further information, see the ICTR website, http://www.unictr.org/Home/tabid/36/Default.aspx .

[17]See, for example, statement by former Minister of Justice Tharcisse Karugarama at the United Nations General Assembly thematic debate on the role of international criminal justice in reconciliation, April 9, 2013, (accessed March 2014). See also New Times, “How the ICTR has let down Rwanda”, February 12, 2014, http://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/index.php?i=15631&a=74471; and New Times, “Rwanda shocked by ICTR acquittals”, February 5, 2013 , http://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/index.php?i=15259&a=63539 (accessed March 2014).

[18]See letters from Human Rights Watch to Hassan Jallow, chief prosecutor of the ICTR, August 14, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/08/14/letter-ictr-chief-prosecutor-hassan-jallow-response-his-letter-prosecution-rpf-crime , and May 26, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/26/letter-prosecutor-international-criminal-tribunal-rwanda-regarding-prosecution-rpf-c

[19]Following an extradition request from Rwanda, Sweden agreed to extradite Ahorugeze in May 2009. Ahorugeze appealed to the ECHR, which, in 2011, upheld the decision of the Swedish court, claiming that he would not risk a flagrant denial of justice in Rwanda. In 2012, the ECHR Grand Chamber decided not to review the case. Ahorugeze is currently living in Denmark. For further information, see TRIAL, http://www.trial-ch.org/en/ressources/trial-watch/trial-watch/profils/profile/476/action/show/controller/Profile/tab/legal-procedure.html (accessed March 2014).

[20]Human Rights Watch agreed with the court's assessment that they would not be guaranteed a fair trial in Rwanda, but criticized the court's decision to release the four men instead of recommending their prosecution in the UK. See letter from Human Rights Watch to UK Justice Secretary Jack Straw regarding amendment of the International Criminal Court Act of 2001, May 12, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/12/letter-uk-justice-secretary-jack-straw-regarding-amendment-international-criminal-co, and Human Rights Watch, "UK: Put Genocide Suspects on Trial in Britain: UK Prosecution Preferable to Extradition,” November 1, 2007, https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/11/01/uk-put-genocide-suspects-trial-britain.

[21]Human Rights Watch, trial observation, High Court of Kigali, 2012 to 2014.

[22]See Human Rights Watch, Law and Reality: Progress in Judicial Reform in Rwanda, July 26, 2008, Annex 2, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/25/law-and-reality.

[23]See letters from Human Rights Watch to Hassan Jallow, chief prosecutor of the ICTR, August 14, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/08/14/letter-ictr-chief-prosecutor-hassan-jallow-response-his-letter-prosecution-rpf-crime , and May 26, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/26/letter-prosecutor-international-criminal-tribunal-rwanda-regarding-prosecution-rpf-c.

[24]See Human Rights Watch, Justice Compromised: the Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/05/31/justice-compromised-0, pp. 119-121.

[25]Some of these laws, such as the 2008 law on genocide ideology, have been used to stifle dissent and prosecute government critics. A revised and improved version of the genocide ideology law was adopted in 2013. Although the new law defines the offense more precisely and requires evidence of the intent behind the crime, thereby reducing the scope for abusive prosecutions, it retains language that could be used to criminalize free speech, and offenses are punishable by up to nine years’ imprisonment.

[26]See Human Rights Watch, Rwanda: Lessons Learned. Ten Years After the Genocide, March 20, 2004, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/english/docs/2004/03/29/rwanda8308_txt.htm, and Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 134-137, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story.

[27]For details of killings of civilians in Burundi in the mid-1990s, see Human Rights Watch, Proxy Targets: Civilians in the War in Burundi, March 1, 1998, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1998/03/01/proxy-targets-civilians-war-burundi. For information about more recent events in Burundi, see Human Rights Watch publications available at https://www.hrw.org/africa/burundi.

[28]Not all of these cycles of violence were caused by or related to the Rwandan genocide. Some stemmed from grievances and tensions between Congolese groups unconnected with events in Rwanda.

[29]See Human Rights Watch World Report 1998, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/worldreport/Africa-10.htm#P816_217123.

[30]For details, see Human Rights Watch, “‘You Will be Punished’: Attacks on Civilians in Eastern Congo”, December 13, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2009/12/13/you-will-be-punished. In addition to the FDLR, numerous Congolese armed groups as well as members of the Congolese army have committed serious abuses against Congolese civilians.

[31]See Human Rights Watch, “‘You Will be Punished’: Attacks on Civilians in Eastern Congo”, December 13, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2009/12/13/you-will-be-punished, pp. 116-117.

[32]For details, see Human Rights Watch, “Germany: Groundbreaking Trial for Congo War Crimes,” May 2, 2011, https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/05/02/germany-groundbreaking-trial-congo-war-crimes, and “Questions and Answers on Trial of Two Rwandan Rebel Leaders”, May 2, 2011, https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/05/02/germany-qa-trial-two-rwandan-rebel-leaders.

[33]See “France: Rwandan Rebel’s Arrest Sends Strong Message”, October 11, 2010, https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/10/11/france-rwanda-rebel-s-arrest-sends-strong-message.

[34]See, “ICC: Pursue Case Against Rwanda Rebel Leader,” June 1, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/06/01/icc-pursue-case-against-rwandan-rebel-leader.

[35]For details and a chronology of some of these warnings, see Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 141-179, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story.

[36]For details of international reactions to the genocide, see Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 130-134, 172-179 and 595-691, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story.

[37]In 2004, on the tenth anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, Human Rights Watch published a set of ten recommendations intended to contribute to a strategy based on the lessons of 1994. See Human Rights Watch, Rwanda: Lessons learned. Ten years after the genocide, March 29, 2004, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/english/docs/2004/03/29/rwanda8308_txt.htm.

[38]For details of France's role and Opération Turquoise, see Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 654-691, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/03/01/leave-none-tell-story.

[39]See, for example, New York Times, “Clinton Makes Up for Lost Time in Battling AIDS”, August 29, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/29/health/29clinton.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed March 2014).; Los Angeles Times, “Clinton Expresses Regret Over 1994 Genocide”, July 24, 2005, http://articles.latimes.com/keyword/rwanda/featured/6 (accessed March 2014).; UN Press release, “Kofi Annan Emphasizes Commitment to Enabling UN Never Again to Fail in Protecting Civilian Population from Genocide or Mass Slaughter”, December 16, 1999, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/1999/19991216.sgsm7263.doc.html (accessed March 2014) and Remarks by Secretary-General Kofi Annan at the Rwanda Genocide Memorial Conference, March 26, 2004, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2004/sgsm9223.doc.htm (accessed March 2014); and BBC, “Belgian Apology to Rwanda”, April 7, 2000, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/705402.stm (accessed March 2014).

[40]For example, in an address to the United Nations General Assembly, President Paul Kagame claimed that the ICC had “shown open bias against Africans” and “served only to humiliate Africans and their leaders, as well as serve d the political interests of the powerful.” See “Address to the 68th UN General Assembly by President Paul Kagame,” New York, 25th September 2013, http://www.presidency.gov.rw/speeches/933-address-to-the-68th-un-general-assembly-by-president-paul-kagame (accessed March 2014). See also comments by Rwanda’s Permanent Representative to the UN, on November 15, 2013, “The explanation of vote by Permanent Representative, Eugene-Richard Gasana, on the UN Security Council resolution on the deferral on the Kenyan cases before the International Criminal Court,” November 15, 2013, http://rwandaun.org/site/2013/11/15/the-explanation-of-vote-by-permanent-representative-eugene-richard-gasana-on-the-resolution-on-the-deferral-on-the-kenyan-cases-befor-the-international-criminal-court/ (accessed March 2014).

[41]For information on the human rights situation in Rwanda since the genocide, see Human Rights Watch publications available at https://www.hrw.org/africa/rwanda.