The World Bank spends tens of billions of dollars every year on “development.” It works in some of the most complex environments around the world, in cooperation with some of the most repressive governments. You’d think it would pay close attention to whether any of these governments are violating human rights with this money. It doesn’t.

But this is a rare moment primed for change as the bank undertakes its first wholesale review of its policies designed to prevent harm to people and their environment. The bank’s Board of Executive Directors met in Washington on Tuesday July 23 to receive its first briefing from the review team. Over the next four months, the review team intends to continue this conversation with the bank’s 188 member countries in their capital cities and through their 25 representatives on the Board of Executive Directors. Through these discussions, finance and development ministers and their board appointees should seize this chance to signal their support for making human rights part of the bank’s development manifesto.

It is bewildering to think that one of the world’s leading development agencies does not explicitly undertake to honor the obligation to respect international human rights law.

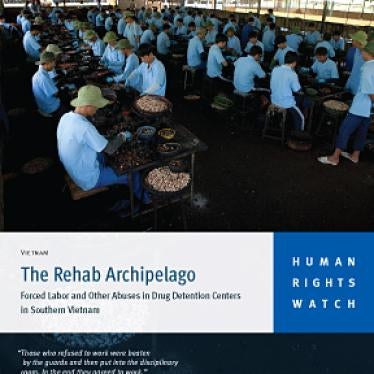

In Vietnam, for instance, the World Bank funded HIV-related services in detention centers where suspected drug users – some as young as 12 – were held without due process, beaten, abused and forced to work. To quote one detainee: “Those who refused to work were beaten by the guards and then put into the disciplinary room. In the end they agreed to work.” Others described how they were beaten with wooden truncheons, shocked with electrical batons, and deprived of food and water.

Uncovering these abuses would not have taken an undercover investigation; the World Bank need only have looked at official documents. Government regulations say that labor therapy (lao dong tri lieu) is one of the official five steps of drug rehabilitation. Decrees that govern the drug detention centers stipulate that work in the centers is not optional and authorize punishing detainees who refuse to obey regulations, including the obligation to work.

The absence of a clear commitment not to support activities that will contribute to or exacerbate human rights violations leaves World Bank staff without guidance on how they should approach human rights concerns or what their responsibilities are. The result is that staff members have unfettered discretion to determine whether they will pay any attention at all to human rights risks, take measures to mitigate or avoid problems, or even whether they will bring them to the attention of senior management or the board.

Introducing a human rights commitment would not be a cosmetic change, but would go to the root of how the World Bank does business. To honor such a commitment, the World Bank would need to carry out systematic human rights due diligence for every program, first to identify how its lending or other support may contribute to violating human rights and then to figure out constructive ways to avoid or mitigate the human rights risks. Such an approach would enable bank staff to minimize suffering, especially among marginalized, excluded, and vulnerable groups, and in doing so make its development efforts more sustainable.

Had it considered the human rights risks in Vietnam, the World Bank would have identified the problems of arbitrary arrest and detention, forced labor, and various violations of children’s rights. Then the bank could have built measures to avoid these risks into its project design—for instance by supporting HIV-specific health services in the community for people released from drug detention centers.

That would have given centers a significant incentive to release sick detainees from arbitrary detention. And it would have aligned bank support with international law and the existing Vietnamese legal framework and avoided a scenario in which HIV-positive project beneficiaries received health care, but were otherwise left in arbitrary detention and forced to work.

This example is indicative of a broader policy that is largely devoid of human rights considerations. While the World Bank has policies on involuntary resettlement and indigenous peoples, even these policies fall short of the international human rights standards.

The World Bank’s ongoing safeguards policy review should set in motion an overdue reform process to finally ground the World Bank in international human rights law. Such reform is essential if the World Bank is to meaningfully achieve its recently adopted goals to end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity in complex environments like Vietnam.

Jessica Evans is the senior advocate and researcher on international financial institutions at Human Rights Watch. You can follow her on twitter @evans_jessica.