On March 20, 2013, the United States Senate held a hearing entitled "Building an Immigration System Worthy of American Values."

Human Rights Watch submitted the following written statement for the record.

--------

Mr. Chairman, Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to submit a statement on today’s hearing on building an immigration system worthy of American values.

Human Rights Watch is an independent organization dedicated to promoting and protecting human rights around the globe. We have been reporting on abuses in the US immigration system, including violations of the right to family unity, for over 20 years. On February 1, we issued a briefing paper entitled, “Within Reach: A Roadmap for US Immigration Reform that Respects the Rights of All People,” which we wish to submit for the record.[1] Our testimony for this hearing will focus on the basic value of fairness, which the United States has long espoused, and how the US immigration enforcement system should better protect the due process rights of all people, from citizens to persons in the country without legal authorization.

A Confusing System, Carrying Serious Consequences with Severely Limited Access to Counsel and Remedies

As it stands today, the US immigration system fails to provide basic due process protections in a variety of circumstances. One of the most apparent is the lack of access to legal counsel. Within the tremendously complex immigration system, stakes run high and losing a case can sometimes mean a permanent bar to returning to the United States—and permanent separation from US citizen or resident family members. Yet non-citizens in that system are only represented by a lawyer if they are able to pay for counsel or can find pro bono assistance. The impact of having counsel is stark: asylum seekers, for example, are three to six times as likely to receive asylum if they are represented by counsel. Without appointed counsel, particularly vulnerable populations, like persons with mental disabilities and children, cannot fairly defend themselves or receive a fair hearing. Once a removal order is final, non-citizens have very limited opportunities to appeal the decision to a federal court. Thus, even when immigration judges make errors, it can be extremely difficult to remedy them, especially when the non-citizen has already been deported.

Even this flawed system of removal proceedings, with its delayed hearings and limited access to counsel, is unavailable to hundreds of thousands of people each year. The majority of deportations are not carried out through orders by an immigration judge but by mechanisms like “stipulated removals,” in which non-citizens accept removal before seeing an immigration judge, or “expedited removals,” in which non-citizens can only offer limited defenses to deportation and are heard not by a judge, but by an immigration officer. Many people caught up in the system have reported being misled about and pressured to accept stipulated removal—even when they may have had valid claims to stay in the country legally—by officials who promised to release them or who assured them, “You can come right back tomorrow.”[2]

Case of Alicia S.

The often dramatic human costs of the lack of adequate due process in the immigration system are illustrated by the case of one deported woman who spoke to Human Rights Watch, “Alicia S.”

“Alicia S.” came to the United States in 2000 without authorization. She found work at a hotel, married another unauthorized immigrant, and started a family. Her daughters, both US citizens, are now 11 and 9 years old. At age 5, her younger daughter’s kidneys began to fail. In 2009, Alicia’s husband was deported (she has not heard from him since). A year later, police stopped Alicia for pulling out of a parking lot without her lights on. Surrounded by several squad cars, she was arrested for not having paid a ticket for driving without insurance, while her daughters cried in the back seat.

That was the last time Alicia saw her daughters. After she spent two weeks in jail, a local judge ordered her released, saying it was wrong for her to be jailed for traffic violations. But immigration authorities then immediately arrested her, and by the next day, she had been deported to Mexico.

Alicia never saw an immigration judge. She most likely agreed, without understanding, to “stipulated removal,” by which she signed a form agreeing to be deported without formal removal proceedings. With no right to appointed counsel, there was no attorney to inform Alicia that she might be eligible to remain legally in the United States.

Based on what Alicia told Human Rights Watch, she may have been eligible for “cancellation of removal.” Under US immigration law, an unauthorized immigrant in removal proceedings can apply for permanent resident status if he or she has been in the United States continuously for ten years, has good moral character, and can demonstrate that a US citizen or permanent resident spouse, child, or parent would suffer “exceptional and unusual hardship” can apply for permanent resident status. According to Alicia’s account, she had been in the United States for ten years and she had no criminal record other than the arrest for driving without insurance. Most importantly, her younger daughter’s medical condition could have supported a strong claim that the child would suffer “exceptional and unusual hardship” if her mother were deported. Alicia’s daughters are now in foster care.

Alicia has tried to cross back into the US three times. She has been abandoned by smugglers without water and food, and she has spent three months in immigration detention and two weeks in federal jail. She also now has a criminal record for a federal immigration offense, most likely illegal entry (she was not sure herself), for which she was sentenced to 13 days. She said, “I begged the judge to forgive me, that I was desperate because of my daughters.” Under US immigration law, because of these attempts to reenter, Alicia now has a permanent bar to returning to the United States.

Blurring the Line between Civil Immigration and Criminal Law Enforcement

The pressure of increased immigration enforcement has also had a significant impact on the federal criminal justice system, as the line between civil immigration enforcement and criminal law enforcement has become increasingly blurred. This is most evident in two areas: the enormous system of immigration detention and the massive rise in prosecutions for illegal entry and reentry, including through programs like Operation Streamline.

1. Immigration detention

To deprive a person of his or her liberty is a grave matter, particularly when it occurs outside the criminal justice system, with its established due process protections. Many non-violent offenses, including minor possession of controlled substances and shoplifting, trigger a “mandatory detention” provision in immigration law, meaning immigrants (including lawful permanent residents) have no opportunity to post bond. By contrast, in the US criminal justice system, no one is held in comparable circumstances (in pre-trial detention, for example) without a hearing to determine if they are a flight risk or dangerous. Immigration detention is supposed to be civil and administrative in nature, rather than punitive, and it should be used as sparingly as possible. As the American Bar Association has recommended, civil detention should be closer in nature to housing in a secure nursing facility or residential treatment facility than to incarceration in a prison.[3]

About half of all immigration detainees have never been convicted of a crime, and even those convicted of a crime have already served any sentences meted out by the criminal justice system. In the last decade, however, an expensive and vast system of detention centers and local jails across the country has held three million non-citizens, without due consideration of whether they are actually dangerous or at risk of absconding from legal proceedings. Numerous detainees, including torture victims and children, have endured punitive conditions in which medical care is grossly inadequate and sexual abuse goes unreported or unaddressed.[4]

Prolonged detention also severely impacts non-citizens’ ability to fight deportation, as continued detention often separates them from their families, limits access to counsel, and leads to financial hardship. Rather than ensuring that immigrants attend removal hearings, such detention impedes their access to a fair hearing.

To maintain its nationwide detention system, ICE has relied on frequent transfers of detainees between facilities, often at long distances that separate the detainee from counsel or from witnesses or family supports. Human Rights Watch has identified over two million detainee transfers between 1998 and 2010.

Case of Kevin H.

One noncitizen in detention who experienced a long-distance transfer told Human Rights Watch:

I lived in upstate New York for 10 years with my four children and my wife. ... ICE said I was deportable because of an old marijuana possession conviction where I never served a day in jail, just paid a fine of $250. ... They took me to Varick Street [detention center in New York City] for a few days and then sent me straight to [detention in] New Mexico. In New York when I was detained, I was about to get an attorney through one of the churches, but that went away once they sent me here to New Mexico.... All my evidence and stuff that I need is right there in New York. I’ve been trying to get all my case information from New York ... writing to ICE to get my records. But they won’t give me my records, they haven’t given me nothing. I’m just representing myself with no evidence to present.[5]

2. Operation Streamline and the rapid growth in federal immigration prosecutions.

Immigration prosecutions now make up over 50 percent of all federal prosecutions, with Customs and Border Protection referring more cases for criminal prosecution than the FBI.[6] At a time when crime rates are down around the country and state prison populations are decreasing, the federal prison population is growing, in large part due to the burgeoning population of non-citizens serving sentences for illegal entry and illegal reentry, prosecutions for which have increased by more than 1400 and 300 percent, respectively, over the past 10 years.[7]

Much of this increase has been fueled by Operation Streamline and similar programs that are active along most of the US-Mexico border, with the notable exception of southern California. Although the program’s name and prosecution policy varies from district to district, what these programs all have in common is a process that is “streamlined,” in which courtrooms packed with dozens, sometimes over 100 defendants, are charged, plead guilty, and are sentenced in a matter of hours. The program is massive but speedy. In some districts, one defense attorney may represent 60 clients, meeting with a client for only 5 to 10 minutes before he or she is convicted of a federal crime. Federal prosecutors must prepare the cases and attend the hearings. Magistrate judges preside over hearings in which they must ensure, as is their duty under the US Constitution, that each defendant understands the charges and the consequences of a plea, despite being charged and convicted en masse. The program requires resources not only from judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys, but also court staff, interpreters, US Marshals, and the Bureau of Prisons. The maximum sentence for illegal entry is six months in federal prison; if a person convicted of illegal entry returns, he or she can be charged with the felony of illegal reentry, which is punishable by up to 20 years in federal prison.

Some judges and prosecutors have questioned whether these prosecutions represent an appropriate use of resources. Our own research indicates thatthe tremendous resources of Streamline are not targeted at people who represent a threat to public safety or national security, but overwhelmingly at people who seek entry to the US for one or more of the following reasons: to find work; to reunite with their American families; or to flee violence and sometimes persecution in their home countries.

Case of Brenda S.

In 2012, “Brenda R.’s” two adult sons were killed in Mexico. She said her sons were not involved in any criminal activity, but one son had befriended a woman said to be the girlfriend of a local drug trafficker, in a small town in the state of Chihuahua, the site of considerable drug-related violence. After receiving threats, Brenda’s son and his brother decided to leave town. But before they could leave, they were gunned down in the parking lot of a bar.

Although she is married to a permanent resident, with whom she has a 10-year-old, US-born daughter, and was a long-time resident of Dallas, Texas, Brenda did not have legal status. This is not surprising. Due to limited visas and enormous backlogs, spouses of permanent residents from Mexico must wait over 11 years to apply for permanent resident status. Anyone who has resided in the United States for over one year without status after entering illegally also must leave the US to apply for legal status, which then triggers a 10-year bar to returning.

Without legal status, Brenda knew that when she left the United States, she would not be able to reenter legally. But as a mother, she felt she had to bury her sons. Once in Chihuahua, she

started asking questions about the police investigation and the woman with whom her son had been involved. Fighting back tears, Brenda remembered that local residents and the police in Chihuahua had warned her to stop asking questions.

Feeling unsafe in Mexico, Brenda tried to return to her family in Texas. When she was caught near the border, Brenda was criminally prosecuted and convicted of the federal misdemeanor of illegal entry.

In desperation at being separated from her American family, Brenda tried again a few months later, this time presenting a friend’s border-crossing permit to a Customs and Border Protection agent. But she was immediately caught and referred again for criminal prosecution.

Brenda had never been in trouble with the law before. She now has a federal criminal record with two illegal entry convictions. She ended up serving a sentence of 60 days in a county jail. She is now in immigration detention, fighting for a chance to remain in the United States.

Because she was previously deported and apprehended at the border, Brenda will not be placed in regular removal proceedings. She will not be allowed to apply for “cancellation of removal,” a form of relief from deportation that would allow an immigration judge to take into consideration her many years of residence in the US and the impact her deportation would have on her permanent resident husband and US citizen daughter. Because of her attempts to enter illegally, she is now permanently barred from gaining legal status through her permanent resident husband or US citizen daughter, absent special permission to apply from the Attorney General. Brenda may apply for asylum, but she will have no right to appointed counsel through a difficult and complex process.

In short, under the current system, all of Brenda’s equities and longstanding ties to the United States will be disregarded.

No Second Chances for Non-Citizens, including Permanent Residents, with Criminal Convictions

Immigration law is particularly harsh on people who face deportation after criminal convictions, even for lawful permanent residents convicted of minor or old offenses. Amendments that went into effect in 1996 stripped immigration judges of much of the discretion they once had to balance family unity against the seriousness of the crime. At the same time, these amendments expanded the definition of “aggravated felony” to include an enormous number of crimes, including nonviolent offenses like shoplifting, making them also grounds for mandatory deportation. Permanent residents who served whatever sentence was imposed by the criminal justice system, have been permanently deported sometimes decades after the offense was committed. Non-citizens deported for an “aggravated felony” are permanently barred from the United States, regardless of their longstanding ties, including to American families. If they return without permission to the US, they are often charged with the federal crime of illegal reentry.

Human Rights Watch has estimated that from 1997 to 2007, 72 percent of non-citizens deported for criminal convictions were deported for nonviolent offenses, and that over one million people experienced family separation due to deportation for a criminal conviction.[8] Given that over a million deportations have occurred since 2007, the number of family members affected is now likely much higher.

Case of Antonio Cerami

Antonio Cerami came to the United States from Italy with his family when he was 12 years old, as a lawful permanent resident. In 1984, he met Cristina, who is a US citizen, and they were married in 1992. Antonio became stepfather to her four children, and the couple had a son of their own.

Cristina told Human Rights Watch, “We were fine, we were just a normal—not a rich—family, but very comfortable, right? I went to work, he went to work, we hardly ever saw each other because we worked for 10 hours. But we had a plain old normal life.”

Then, in 2003, Antonio decided to take his young son and wife on a three-week trip to Italy for a niece’s wedding. Upon their return to Chicago’s O’Hare airport, Antonio was taken into custody in connection with a conviction he had received 19 years earlier for participating in the attempted robbery of a pizza parlor. Antonio had been sentenced to six years in prison and released after three years for good behavior. Although he had since complied with all conditions of his parole and lived without further troubles with the law for over 15 years, Antonio was ordered deported back to Italy. Although his family begged the immigration judge “not to take Tony away,” the judge had no power to take into account Antonio’s many years of good behavior.

Cristina’s youngest son had to undergo counseling after his father was deported. With the loss of Antonio’s income and expensive legal fees, Cristina lost their house in the suburbs. Her oldest daughter moved in with her boyfriend’s family and, Cristina explained, “Right now we don’t really have a home.… John lives with a friend, Jessica lives with another friend, Danny’s with his uncle and Angela lives with another friend. They have really split us up.”[9]

Recommendations for building a fairer immigration enforcement system

Congress should:

- Restore discretion to immigration judges to weigh evidence of rehabilitation, family ties, and other equities against a criminal conviction in deciding whether to deport lawful permanent residents.

- Ensure that lawfully present non-citizens, and those non-citizens whose legal status is in dispute, who are facing removal, have access to judicial review and appeal to a higher authority, as required by international human rights law. In addition, ensure that detained individuals, including those detained pending deportation, have access to judicial review of the decision to detain them.

- Reform the expedited removal process to allow for a fairer and more complete review of a non-citizen’s arguments against deportation.

- Ensure immigration judges provide custody hearings for “arriving aliens” on an individual basis and review all deportation orders in order to reduce the risk of wrongful deportation.

- Make legal counsel available to indigent vulnerable immigrants, such as mentally illpersons and children, facing deportation or seeking asylum.

- Eliminate arbitrary deadlines currently in law, such as the one-year limit to apply for asylum.

- Halt Operation Streamline’s expansion and evaluate the need for continuing operation of such programs; ensure that criminal immigration prosecutions focus on those who pose a real threat to public safety or national security.

-

Reform immigration detention by:

- Limiting mandatory detention to violent offenders.

- Not subjecting lawful permanent residents and asylum seekers to mandatory detention (unless they are shown to be a safety or flight risk).

- Expanding the limited alternatives-to-detention programs currently in use.

- Prohibiting all long-distance transfers of detainees that could interfere with assistance of counsel or unduly separate detainees from their families.

- Ensuring proper treatment of detainees, including access to adequate medical care.

[1] Human Rights Watch, Within Reach: A Roadmap for US Immigration Reform that Respects the Rights of All People, February 1, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/02/01/us-immigration-reform-should-uphold-r....

[2] Human Rights Watch interview with Elizabeth (last name withheld), San Juan, Texas, September 16, 2012. See also Jennifer Lee Koh, et al., “Deportation Without Due Process,” a joint publication of Western State University College of Law, Stanford Law School, and the National Immigration Law Center, 2011, http://www.law.stanford.edu/publications/deportation-without-due-process (accessed January 8, 2013).

[3] American Bar Association, “ABA Civil Immigration Detention Standards,” 2012, http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/immigration/ab... (accessed January 22, 2013).

[4] See Human Rights Watch, Detained and At Risk: Sexual Abuse and Harassment in United States Immigration Detention, August 25, 2010, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2010/08/25/detained-and-risk-0; and Human Rights Watch, Detained and Dismissed: Women’s Struggles to Obtain Health Care in United States Immigration Detention, March 17, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2009/03/16/detained-and-dismissed.

[5] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Kevin H. (pseudonym), Otero County Processing Center, Chaparral, New Mexico, February 11, 2009.

[6] Migration Policy Institute, “Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery,” January 2013, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/enforcementpillars.pdf.

[7] Transaction Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), TRAC Data Interpreter Tool, “Prosecutions for 2012, Lead Charge: 08 USC 1325” (noting the percent change in prosecutions from 10 years ago is 1405), and “Prosecutions for 2012, Lead Charge: 08 USC 1326” (noting the percent change in prosecutions from 10 years ago is 298), http://tracfed.syr.edu/index/index.php?layer=cri (accessed March 19, 2013).

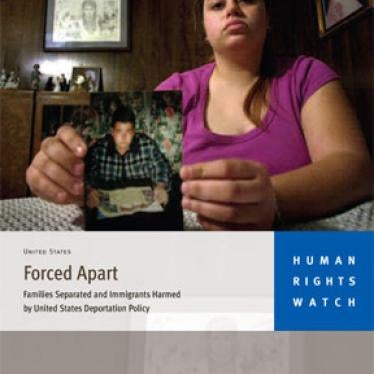

[8] Human Rights Watch, Forced Apart: Families Separated and Immigrants Harmed by United States Deportation Policy, July 17, 2007, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2007/07/16/forced-apart-0.

[9]Human Rights Watch interview with Cerami family, Chicago, Illinois, February 5, 2006, in Human Rights Watch, Forced Apart: Families Separated and Immigrants Harmed by United States Deportation Policy.