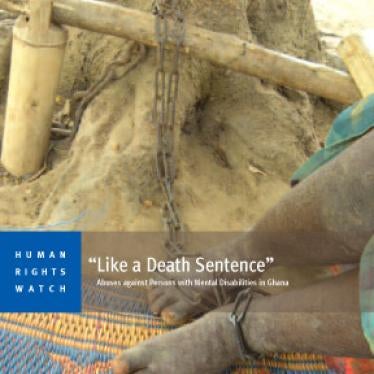

When we met Elijah early this year in Ghana, he was chained to a tree at a “prayer camp.” Five months earlier, his family had him bound with rope and forcibly taken to the camp for “treatment.” Elijah told me that he had been chained to the tree ever since – the “healing” prescribed for the restlessness and insomnia that his parents and the camp’s spiritual leaders had decided was a mental disability.

Elijah said he longed to sleep indoors, and to have some measure of privacy. But he will probably remain chained to that tree, where he sleeps, bathes, and defecates in an open compound, until the camp’s spiritual leader, known as a “prophet,” has decided he has been cured and can return home.

Elijah was one of dozens of people I interviewed while researching how Ghana treats its 2.8 million residents with mental disabilities (mental health problems) including thousands in psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps.

My interest in disability rights is rooted in my experience living with a physical disability in Uganda. I already knew that in Uganda people with mental disabilities are the objects of stigma, discrimination, and sometimes serious abuse. I chose to go to Ghana because it is one of the leading democracies in Africa with one of the fastest growing disability rights movements, and I thought things would be better there.

But I was mistaken. Based on what I witnessed in three public psychiatric hospitals, eight prayer camps, and communities all over the country, Ghana still has a long way to go to ensure that people with mental disabilities enjoy the same rights as other citizens.

Many of the people with mental disabilities we met in Ghana had been admitted against their will to overcrowded and unsanitary psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps. In one psychiatric hospital, there were only three nurses for more than 200 patients. The patients were often locked in their rooms or injected with sedatives to manage them. In some hospitals and prayer camps, many also lived among urine and feces because the staff had no time to clean. In hospitals, people either took their medication peacefully or were forced to. Some were beaten for resisting.

What I witnessed in the prayer camps was even worse. These privately owned Christian religious institutions operate throughout Ghana. In some, “prophets” treat people with mental disabilities through prayer and traditional medicines, like herbs. Administrators and pastors in seven of the camps I visited said that mandatory fasting – in some cases, as long as 12 hours a day, for 7 to 40 days – was a key component of their “treatment.”

In Jesus Divine Temple (often called Nyakumasi Prayer Camp), where I met Elijah and about 20 other people - including a 10-year-old child – all people with mental disabilities lived just like Elijah: with no shelter, chained to trees outdoors in a forest. Almost all of them complained of hunger, either because they were forced to fast or because the camp appears not to have provided food, putting that responsibility instead on their families.

At Heavenly Ministries Spiritual Revival and Healing Center (called Edumfa Prayer Camp), I met people who were chained to the walls of a very small, hot room. The buckets they used to relieve themselves were in that same room and it reeked of urine and feces.

In some camps, such rooms were locked even at midday when we visited – even though people with mental disabilities inside, some children as young as 9, were chained and could not leave. In any event, there was no place for many of them to go. Some people told me they had been abandoned there by family members. Family members and caregivers also said they had taken their relatives to the prayer camp because there was nowhere else they could get treatment.

The abuses we documented in state-run psychiatric hospitals, and in prayer camps, which operate without any government oversight, amount to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. Forcible detention and assault are also crimes in Ghana. But these crimes are never prosecuted. Public officials, caretakers, and even family members generally accept that people with mental disabilities can be treated this way.

We also spoke to people with mental disabilities who were living in the community. While they complained that they faced stigma and lacked access to medication, food and shelter, they were also relieved to be living with their families and not in institutions.

International donors have poured millions of dollars of development aid into Ghana, funding nearly 15 percent of Ghana’s health budget. But government budgetary allocations for mental health are less than 6 percent of the national health budget. And none of the international development partners with whom I spoke, such as the World Bank and USAID, had mental health services on their agendas.

In July, the government of Ghana ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This is proof of its commitment to ensuring the health and human rights of people with mental disabilities. Now Ghana needs to set up a system for people with mental disabilities to access support and effective treatment in their communities, rather than being consigned to abusive psychiatric hospitals and prayer camps. And while the government is setting up such a system, it needs to take immediate steps to end these horrific abuses.

Ghana has provided an example for African stability and peaceful political transition. If it takes these steps, it will offer regional leadership in mental health. And it will also provide millions of its people living lives of misery and torment the prospect of a productive and satisfying future.

Editor’s note: Medi Ssengooba is the Finberg fellow at Human Rights Watch, working in the field of disability rights and the primary author of a new report, “Like a Death Sentence: Abuses against Persons with Mental Disabilities in Ghana.”