As the US confronts a growing population of geriatric prisoners, it is time to reconsider whether they really need to be locked up. Prison keeps dangerous people off the streets. But how many prisoners whose minds and bodies have been whittled away by age are dangerous?

According to prison statistics, hardly any.

In Ohio, 26.7 percent of former prisoners commit new crimes within three years of their release from prison. But only 5.6 percent of those released between the ages of 65 and 69—and 2.9 percent of those released between the ages of 70 and 74—commit new crimes. Of those released at age 75 or older, none revert to criminal behavior.

In New York, you can count on two hands the number of older prisoners who have gone on to commit violent crimes after release.

Of 1,511 prisoners aged 65 and older when released between 1995 and 2008, only 8 were returned to prison for committing a violent felony. Among the released older prisoners were 469 who had originally been sent to prison because of a violent crime. Only one has returned to prison because of a new crime of violence.

These statistics quantify what criminal justice professionals know from experience: as a group, released older prisoners are not likely to pose much of a risk to the public. The risk is no doubt even less if the released prisoners are ill or infirm.

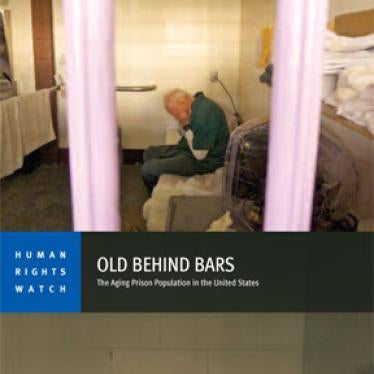

Among the more than 26,000 state and federal prisoners aged 65 or older are some who have severe physical and mental impairments.

One 87-year-old I met last year while conducting research on older prisoners could not tell me his name. He had been in prison for 27 years, 20 of them in a special unit because of his severe cognitive impairments.

I met prisoners who were dying and could not breathe without assistance; prisoners so old and frail they needed help getting up from their bed and into their wheelchairs; prisoners who lacked the mental and physical ability to bathe or eat or go to the bathroom by themselves.

In theory, of course, a deathly ill or feeble prisoner could suddenly rise from his bed and commit a serious crime. But it isn’t likely.

Noting the forgetfulness that can come with old age, one prisoner told me that by the time one of “these guys manages to get up from his wheelchair he’ll have forgotten what he was going to do.”

Wholly apart from the effects of age and infirmity, years in prison also leave older prisoners with little desire to pick up a gun or hit the streets looking for trouble even if they were physically able to do so. They want to spend their remaining time on earth with family and friends. They do not want to die behind bars.

Ensuring just deserts for those who harm others is a legitimate criminal justice goal. But age and infirmity can change the calculus of when the time served is long enough.

At some point in a prisoner’s life, parole supervision and perhaps restrictions on movement (e.g. home confinement) may suffice as a cost-effective and sensible punishment. It won’t satisfy those who think prisoners who have killed or maimed should only leave prison in a pine box. But, while understandable, this “eye for an eye” perspective is not a sound basis for determining how to use scarce prison resources.

The growing number of prisoners who use walkers and wheelchairs, are tethered to oxygen tanks or completely bedridden, is forcing the country to ask why we keep people in prison into their dotage

Most states and the federal government have laws permitting the early release of prisoners who are terminally ill, permanently incapacitated , or in some cases, simply old, as long as public safety would not be jeopardized.

Unfortunately, the laws exclude certain prisoners based on the nature of their crimes (e.g. those convicted of murder); or officials making release decisions decide to exclude them because of those crimes. In either case, the public is being short-changed. Past crimes—even brutal ones—should not be automatically conflated with current risk.

Protecting public safety does not require turning prisons into old-age homes. Jamie Fellner is Senior Advisor to the US Program of Human Rights Watch and author of Old Behind Bars: The Aging Prison Population in the United States. She welcomes comments from readers.