There are good reasons to be optimistic about Burundi. The country is emerging from decades of civil war and brutal ethnic conflict. In 2011, the government put in place a National Independent Human Rights Commission that has started to tackle sensitive issues, such as extrajudicial killings by the police. Burundi has also taken tentative steps to create a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which may prove vital in healing the wounds of the past, and which the president has pledged to have in place by the end of 2012.

Through these actions, the government has demonstrated to its people and to the wider international community that it cares about accountability for abuse.But on May 2, Interior Minister Edouard Nduwimana blocked a Human Rights Watch news conference and the distribution of a report on the 2011 political violence in the country.

With those actions, the government showed that it remains intolerant of public criticism. Instead of using the report to discuss the need for justice for political killings, the government pre-empted valuable dialogue about how to fulfil important human rights commitments.

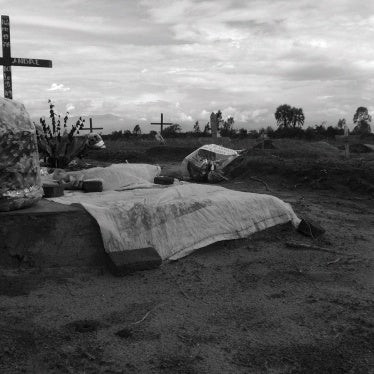

The Human Rights Watch report, “You Will Not Have Peace While You Are Living”: The Escalation of Political Violence in Burundi, documents patterns of political killings following a difficult electoral period in 2010. The killings fall into three main categories: violence committed by state agents or members of the ruling CNDD-FDD party against current and former opposition members; violence by people aligned with opposition movements targeting members of the ruling party; and larger-scale attacks in which the killers have not been identified, the most notable being an attack at a crowded bar in the town of Gatumba in September in which at least 37 people were killed.

Human Rights Watch was in frequent contact with Burundian government officials throughout 2011 as we conducted our field-based investigations. Our researchers formally corresponded with the national prosecutor in September 2011 to seek official information about some of the most worrying cases of political killings.

On April 20, prior to publication of the report, Human Rights Watch wrote to External Relations Minister Laurent Kavakure and five other ministers to request meetings in Burundi to discuss our findings and recommendations. We delivered invitations to the news conference on April 26 to all relevant ministries and the president’s office.

Despite these communications, the interior minister informed Human Rights Watch on April 30 that our news conference should be cancelled. On the same day, a local government official, accompanied by a policeman, went to the Bujumbura hotel that Human Rights Watch had booked for the event and told them to cancel the reservation for the room.

On May 1, the police told Human Rights Watch that the news conference would not be allowed, and on May 2 — the report’s publication date — the police ordered Human Rights Watch’s researchers to immediately stop distributing the report, just three hours after they had started delivering copies.

The interior minister’s course of action is shortsighted and highly unusual in Burundi, where local and international organisations frequently hold news conferences without difficulty and without seeking prior authorisation. These organisations also regularly publish and broadcast reports and statements.

Burundi, to its great credit, has a strong civil society and a vocal independent media. But, in their day-to-day activities, these civil society groups and journalists encounter persistent harassment and intimidation, and the government has repeatedly accused them of being mouthpieces for the opposition.

The interior minister’s cancellation of the Human Rights Watch news conference and its attempt to block distribution of the report is mild in comparison with the way some Burundian officials routinely persecute local activists. Indeed, a section of the Human Rights Watch report on the 2011 political violence explores the government’s tendency to “blame the messenger,” rather than address the root causes of violence.

Instead of trying to silence organisations and individuals that denounce abuse, Burundi should prove it is capable of addressing political violence. Burundian and international human rights organisations are not enemies of the state. We want to engage in meaningful dialogue with the government to find effective solutions for a more peaceful and prosperous future in Burundi.

Now is a good time to undertake that collaborative reflection. Politically motivated killings, which dominated the news throughout 2011, have diminished significantly. There are considerably fewer announcements by the local media of newly discovered dead bodies.

Since early 2012, residents of the most affected areas outside the capital Bujumbura reported a sense of calm that had not been felt since before the 2010 elections.Burundi’s government should take advantage of the current calm to address the widespread impunity that has accompanied the political violence of 2011.

Only by engaging with local and international partners, and being prepared to listen to uncomfortable truths, will the government demonstrate a commitment to human rights and justice.

Daniel Bekele is Africa director at Human Rights Watch