“You Will Not Have Peace While You Are Living”

The Escalation of Political Violence in Burundi

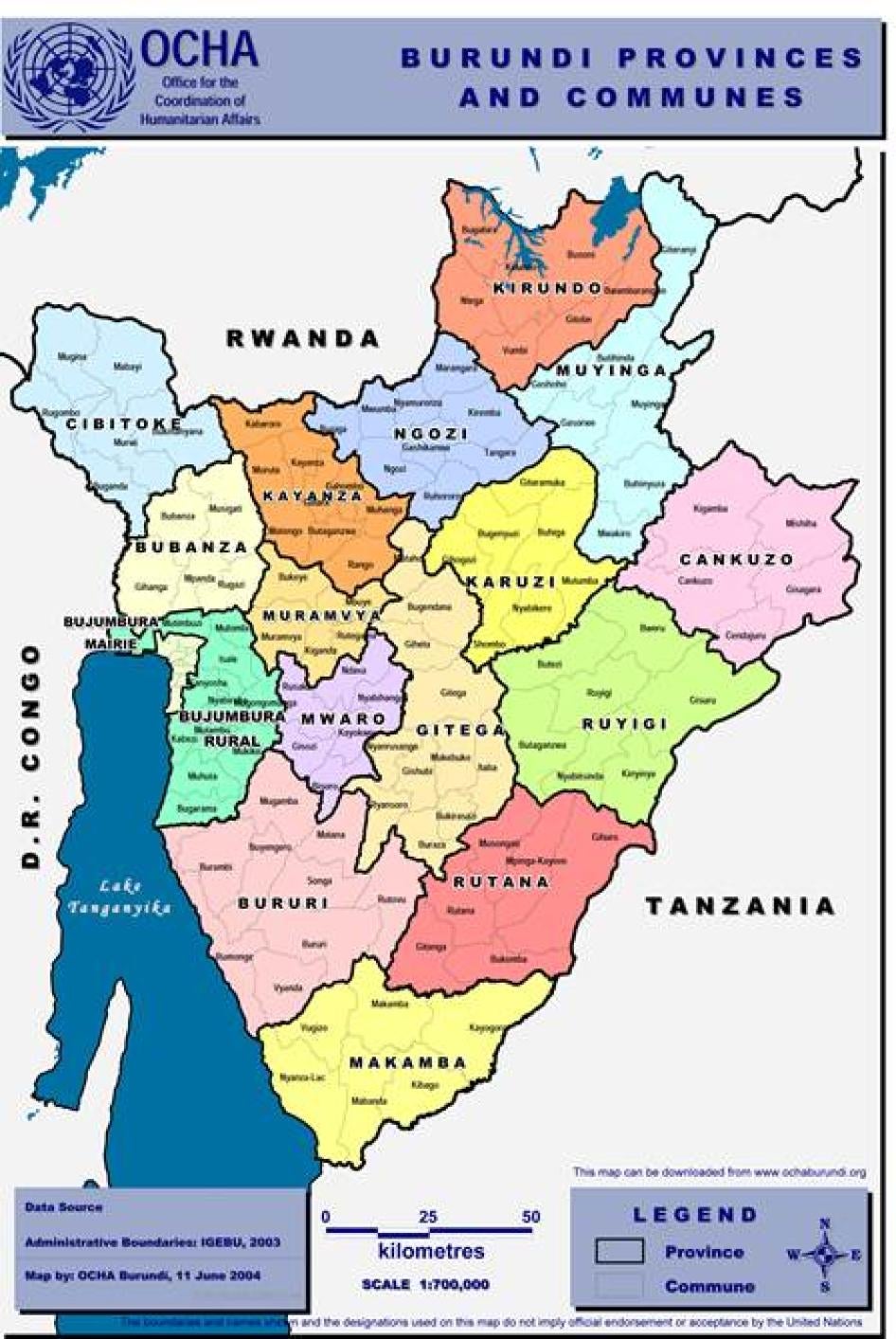

Map of Burundi

Map provided courtesy of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Glossary of Terms and Acronyms

|

ADC-Ikibiri |

Alliance of Democrats for Change (Alliance des démocrates pour le changement), a coalition of opposition parties formed in June 2010. |

|

APRODH |

Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (Association pour la protection des droits humains et des personnes détenues), a Burundian human rights organization. |

|

BNUB |

United Nations Office in Burundi (Bureau des Nations Unies au Burundi). |

|

CNDD-FDD |

National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces pour la défense de la démocratie), currently the ruling party in Burundi. |

|

CNIDH |

National Independent Human Rights Commission (Commission nationale indépendante des droits de l’homme). |

|

DRC |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

|

FNL |

National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération), a former rebel group, led by Agathon Rwasa, that became a political party in April 2009. |

|

FRODEBU |

Front for Democracy in Burundi (Front pour la démocratie au Burundi), a political party. |

|

GMIR |

Mobile Rapid Intervention Group (Groupement mobile d’intervention rapide), a unit of the national police. |

|

Imbonerakure |

The CNDD-FDD youth wing. |

|

MSD |

Movement for Solidarity and Democracy (Mouvement pour la solidarité et la démocratie), a political party founded in 2007 by former Radio publique africaine (RPA) journalist Alexis Sinduhije. |

|

RPA |

African Public Radio (Radio publique africaine), a private Burundian radio station. |

|

SNR |

National Intelligence Service (Service national de renseignement). |

|

TRC |

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. |

|

UPD-Zigamibanga |

Union

for Peace and Development (Union pour la paix et le développement), |

Summary

For many Burundians, 2011 was a dark year, marked by alarming patterns of political violence. Scores of people have been brutally killed in politically motivated attacks since the end of 2010. The state security forces, intelligence services, members of the ruling party and members of opposition groups have all used violence to target real or perceived opponents. The victims have included members and former members of political parties; members of their families; other individuals targeted because of their presumed sympathy with the ruling party or the opposition; demobilized rebel combatants; and men, women, and children with no known political affiliation who simply found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Political killings escalated throughout the year, with a string of targeted assassinations and a pattern of reprisals: killings of opposition sympathizers were quickly followed by killings of ruling party sympathizers, and vice-versa, leading to a cycle of violence that neither side seemed prepared to break.

Human Rights Watch conducted extensive field research in Burundi in 2011 and early 2012 to document individual cases and patterns of political killings across the country. The research also focused on steps taken by government and judicial authorities in response to the political violence. The decision to conduct this research was motivated by the escalation of violence throughout 2011 and the overwhelming absence of justice for the majority of these crimes. Most of the information in this report is drawn from face-to-face interviews with victims of political violence, their relatives, eye-witnesses of attacks, government and judicial officials, members of civil society organizations, investigative journalists, and other sources.

In September 2011, the single most deadly attack in Burundi for several years took place in Gatumba, near the Congolese border: at least 37 people were killed when gunmen burst into a bar and shot indiscriminately at the crowd. The findings of Human Rights Watch’s investigation into this incident are presented in detail in this report. The exceptional scale of the Gatumba attack elicited a strong public reaction by the Burundian government: it vowed to find the perpetrators within a month and set up a commission of inquiry. The attack was also widely covered in the international media. However, most of the other incidents were barely reported, other than by a few Burundian radio stations and newspapers.

Common to almost all these incidents is the blanket impunity protecting the perpetrators. In the vast majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the individuals responsible for ordering or carrying out these killings have not been arrested, charged or tried, even when they have been identified by witnesses. Not only has the state failed to take reasonable steps to ensure security and provide protection for its citizens, it has also not fulfilled its duty to take all reasonable measures to prevent and prosecute these types of crimes.

The impunity has been particularly striking in cases where the perpetrators are believed to be linked to the security forces or the ruling party (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy, Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces pour la défense de la démocratie, CNDD-FDD). In these instances, most of the victims were members or former members of the National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération, FNL), one of the main rebel groups during Burundi’s civil war, which turned into a political party in 2009. In a minority of cases, members of other opposition parties, such as the Front for Democracy in Burundi (Front pour la démocratie au Burundi, FRODEBU) and the Movement for Solidarity and Democracy (Mouvement pour la solidarité et la démocratie, MSD), were also targeted by state agents or members of the ruling party.

In most of the cases Human Rights Watch has documented, there has been no judicial process at all. At best, there have been cursory investigations that have not been followed by arrests or prosecutions. In some particularly sensitive cases in which police officers or other state agents may have been implicated, government or judicial authorities actively blocked investigations and obstructed the pursuit of justice.

Even in cases where the victims were members of the ruling CNDD-FDD, it has been difficult for the victims and their families to obtain justice. In some cases, the police carried out arrests and prosecutors opened casefiles, but these casefiles often lacked critical evidence, and the process of pushing the cases through the courts was painfully slow. In some cases, local residents and individuals close to the victims have privately questioned whether those arrested may have been scapegoats, believing that the real perpetrators were still at large.

In the one case where arrests and a trial took place relatively quickly (the September 2011 Gatumba attack), there were doubts about the fairness of the trial which was marred by serious irregularities, with several defendants claiming to have been tortured.

Several factors have impeded the search for justice for political killings in Burundi. Some of the alleged perpetrators have been protected for political and other reasons; this has been exacerbated by a weak and under-resourced justice system which, additionally, suffers from lack of independence. Furthermore, witnesses and relatives of victims have often been afraid to testify for fear of reprisals. Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which individuals who reported incidents to the police or judicial authorities were repeatedly threatened by people linked to the killings. Some victims’ relatives who, despite such threats, pressed for justice, have done so in vain. Most of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing for their safety. The state has been unable or unwilling to provide security for witnesses.

These killings have taken place in a post-election context in which none of the main protagonists have been prepared to engage in meaningful political dialogue or reconciliation without resorting to violence, or the threat of violence. The CNDD-FDD consolidated its hold on power in 2010, following the victory of President Pierre Nkurunziza in an election he contested as the sole presidential candidate: most of the opposition parties boycotted the polls, alleging widespread fraud in the first set of local elections. Despite significant internal divisions, the ruling party remains in a strong position, while the opposition − also facing internal divisions − is fragmented and weak.

Many opposition leaders have been living in exile since the 2010 elections; the coalition of opposition parties, the ADC-Ikibiri, is not officially recognized. Opposition leaders living in exile have refused to return to Burundi, despite public reassurances and invitations by the president, partly out of fear for their safety and partly because some do not believe that the government’s overtures are in good faith. In this political impasse, both sides have resorted to violence to settle scores, and occasional international pressure and quiet diplomacy to find a peaceful solution have not been successful. FNL elements and other opposition groups have retreated to the bush and to bases in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and taken up arms once again, while elements of the security forces and other individuals close to the CNDD-FDD have carried out targeted assassinations against their opponents.

Burundi has only recently emerged from more than a decade of civil war and brutal conflict. After the 2005 and the 2010 elections, there were hopes that the country would return to normality and that Burundians could begin enjoying peace and security once again. Unfortunately, for many, those hopes have been dashed. The recent violence in the country has not been on the scale of the violence that took place in the 1990s, with the exception of the September 2011 Gatumba attack. Most of the recent killings have taken the form of individual, targeted assassinations, rather than large-scale massacres. They have also tended to be concentrated in certain provinces, notably in areas of the capital Bujumbura and the surrounding province of Bujumbura Rural. With the exception of a few cases in other provinces, such as Gitega and Kayanza, the rest of the country has remained relatively calm. Nevertheless, the number of victims quickly adds up: during the worst periods in 2011, barely a week went by without a fresh report of an apparently politically motivated murder. The population in the affected areas continues to live in fear, and many people have abandoned their homes in search of safety.

Pushed into a defensive position by the increase in attacks by armed groups − including on police posts and other government targets − the government has lashed out not only at its political or armed opponents, but also at civil society activists and journalists who have documented and denounced the violence. In 2011, leading human rights activists and journalists were repeatedly harassed, intimidated, and called in for questioning by judicial authorities after publishing or broadcasting reports on political killings and other human rights abuses. In public speeches, senior government officials, including President Nkurunziza, have issued strongly-worded warnings to civil society organizations and the media in response to their denunciations of political killings, accusing them of inciting civil disobedience and of being tools of the political opposition.

Alongside these negative trends, some positive human rights developments have taken place in Burundi. In 2011, the newly-established National Independent Human Rights Commission (CNIDH) finally began its work; it was able to launch investigations and publish statements on its findings, including on sensitive issues such as extrajudicial killings. Despite harassment and intimidation, Burundian civil society organizations remain active, denouncing abuses and campaigning for justice. Human Rights Watch, whose Burundi-based researcher had been expelled in 2010, was allowed back into the country, and its staff visited Burundi a number of times in 2011 and 2012. Senior government and justice officials made explicit commitments to bring to justice individuals responsible for political killings and other human rights abuses, including in several meetings with Human Rights Watch.

Burundi also made progress towards establishing a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on serious crimes committed during Burundi’s successive conflicts since 1962. A government-appointed technical committee tasked with preparing the creation of the TRC submitted its report in October 2011. The report was made available to a number of organizations and individuals, including members of civil society, in late December 2011. The president has given assurances that the TRC will be established in 2012. If the process is handled impartially and sensitively, it could go some way towards addressing the unresolved political and ethnic tensions which are the legacy of decades of violence in Burundi. Human rights organizations have welcomed moves to establish a TRC but have raised several concerns, including about the composition of the TRC and the government’s lack of firm commitment to establishing a tribunal to try these crimes.

Human Rights Watch welcomes these developments, as well as the verbal commitment by senior government and judicial officials − expressed publicly as well privately − to improve the human rights situation in the country. However, Human Rights Watch is concerned that despite these promises, attacks and other types of political killings have continued; many of the victims are yet to obtain justice; and perpetrators of these crimes remain at large.

Human Rights Watch urges the Burundian government to take prompt measures to end the impunity protecting those responsible for political killings and to prevent further killings, including by its own security forces, supporters and sympathizers. Leaders of opposition parties and groups also have a responsibility to take immediate action to dissuade their members from attacking their opponents and to make clear that they do not sanction such crimes.

At the international level, foreign governments, UN bodies and others concerned about the situation in Burundi should maintain pressure on all sides to prevent further killings and call on them to hold their members and supporters to account. International donors should also advocate strongly for the protection of journalists and civil society activists in Burundi.

Methodology

This report focuses on politically motivated attacks and targeted assassinations between late 2010 and December 2011. The cases presented in this report represent just a small sample of the overall number of killings. They have been chosen to illustrate the main patterns and to draw attention to some of the most serious incidents. This report does not document the equally serious problems of political arrests and detention, ill-treatment, and other abuses that have continued in Burundi alongside these acts of violence. Human Rights Watch has also gathered evidence of these human rights abuses, but prioritized research on political killings in 2011 in view of the escalation of such violence during this period.

Several organizations, including the United Nations Office in Burundi (BNUB) and Burundian human rights organizations, have advanced figures of political killings ranging from 40 to 300. On the basis of its own research, Human Rights Watch estimates that at least scores of people have been killed since the end of 2010. It has proved difficult to advance a more precise figure, as there are few, if any, comprehensive or reliable records of these incidents, and Human Rights Watch was able to document only a proportion of reported cases.

Some of the killings documented by Human Rights Watch were carried out by members of the security forces, intelligence services or individuals linked to the ruling party, others by suspected members of armed opposition groups, and others by perpetrators whose identity Human Rights Watch has not been able to confirm. Human Rights Watch’s research focused on cases where there seemed to be a clear political dimension. Cases that appeared to be common crimes or where there were no indications of political motive are not included in this report.

Principal research for this report was carried out between February 2011 and January 2012. Human Rights Watch researchers and consultants conducted interviews in the provinces of Bujumbura Mairie (Bujumbura town), Bujumbura Rural, Muramvya, Gitega, Cibitoke and Bubanza, and also interviewed witnesses from other provinces.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed numerous victims and eye-witnesses of incidents of political violence, relatives and friends of victims, journalists, members of civil society organizations and international nongovernmental organizations, members and former members of political parties, national and local government officials, judicial personnel, police officials, foreign diplomats, and United Nations officials.

Additionally, Human Rights Watch representatives met senior government officials including President Pierre Nkurunziza, the first vice-president, the minister of interior, the minister of foreign affairs, the minister of justice, the minister of public security, the minister of defense, the prosecutor general, and the ombudsman. Human Rights Watch researchers also held several meetings with the National Independent Human Rights Commission. Government officials’ responses to cases and concerns raised by Human Rights Watch are referenced in this report. Correspondence between Human Rights Watch and the prosecutor general on specific cases of political killings is also referenced in the relevant sections.

Because of fear of reprisals, the names of witnesses, family members and friends of victims who spoke to Human Rights Watch have been withheld from this report except in cases in which individuals gave their consent to be cited.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed multiple sources for each case in order to confirm and validate the reliability of testimony.

Most interviews were conducted in French or in Kirundi with the assistance of interpreters. Some interviews were conducted in English or in Kiswahili, again with the assistance of interpreters.

Recommendations

To the Government of Burundi

- Give clear and public instructions to the security forces and intelligence services that extrajudicial killings will not be tolerated, and that any individual suspected of carrying out or ordering assassinations or other grave human rights abuses will be brought to justice.

- Immediately investigate the role of individuals in the security forces and intelligence services alleged to have participated in or ordered political killings, and suspend them from active duty until investigations have been completed. This includes high-level members of the security forces where there is evidence that they may have been involved in ordering or condoning killings or related human rights abuses.

- Remind the security forces that individuals suspected of involvement in armed activities or other criminal offences should be arrested. If there is sufficient and credible evidence, these individuals should be charged with a recognizable criminal offense and brought before a court, according to due process and in conformity with Burundian law.

- Remind the security forces that violence should not be used as a substitute for arrest and prosecution, that law enforcement officials should only use force as a last resort, and that they should respect the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials at all times.

- Issue clear instructions to the security forces and intelligence services that under no circumstances should persons be targeted for attack, intimidation or threat on account of their past or present political affiliations, and issue similar directives to the hierarchy of the ruling party, the CNDD-FDD.

- Call on leaders of the ruling party and the intelligence services to respect the right of former or demobilized combatants to resume a normal civilian life and to participate in or abstain from political activities. Put an immediate end to the pattern of pressure and threats on former FNL members to join the ruling party or the intelligence services.

- Ensure that investigators, prosecutors and other judicial personnel prioritize and accelerate investigations and prosecutions of political killings, including, but not limited to, the cases mentioned in this report. Ensure that thorough investigations are carried out into all reported cases, in an impartial manner, regardless of the political affiliation of the victims or perpetrators. Ensure that police investigators are trained in fact-finding and information gathering.

- Strengthen measures to protect witnesses’ safety and proactively encourage witnesses of political killings to report such cases and to testify with a view to bringing the perpetrators to justice. Encourage witnesses to report any threats they may receive as a result of testifying, and bring to justice those responsible for these threats.

- Remind the police that it is their duty to ensure, in an impartial manner, the safety and protection of all Burundians, regardless of their political sympathies.

- Respect and promote the independence of judicial institutions and refrain from interfering in the course of justice.

- Provide adequate support to judicial authorities, including prosecutors and police, to allow them to carry out their work effectively.

- Stop intimidating and harassing journalists, human rights activists and other members of civil society and allow them to carry out their work, including investigating and reporting on human rights abuses, without hindrance.

To Leaders of Political Parties and Opposition Groups

- Make clear public statements that the party or group does not support and will not tolerate political killings, attacks, threats or acts of intimidation by its members, and that involvement in such activities is incompatible with membership of the party or group. Ensure that their governing documents, such as party constitutions, principles and rules, do not contain wording that could be interpreted as supporting violence in any form.

- Fully cooperate with judicial authorities investigating political killings and related abuses, including by providing relevant information on such incidents.

- Remind their members that political killings and other human rights abuses by their opponents can never justify retaliation.

- Take immediate measures to assist the authorities to disarm and control party youth groups and ensure that they stop attacking and threatening perceived opponents.

To Foreign Governments and Inter-Governmental Organizations

- Continue to express concern about political killings by all sides in Burundi, raising specific cases where appropriate, and urge the authorities to take effective action to bring the perpetrators to justice and prevent further killings (as recommended above).

- Call on the Burundian government to publish the reports of the commissions of inquiry it has set up to investigate killings since 2010, including the inquiry on the September 2011 Gatumba attack.

- Provide support to the Burundian justice system (for example in the form of financial or technical assistance, investigative expertise or training) to strengthen its capacity and to enable it to process the large number of cases of killings within a reasonable timeframe.

- Ensure that support provided to the Burundian military or police, whether in the form of technical assistance or training, includes a strong human rights training component with practical as well as theoretical application.

- Urge leaders of political parties and opposition groups to implement the relevant recommendations in this report.

- Advocate for greater freedom of expression, including press freedom, and protection for journalists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists in Burundi.

- Continue supporting and strengthening the National Independent Human Rights Commission.

I. The Context: The 2010 Elections and their Aftermath

The political violence of 2011 did not occur in a vacuum. In order to understand its causes, it should be analyzed in the context of the 2010 elections, the near total control of the political scene by the CNDD-FDD, the marginalization of the political opposition, and the way politicians on all sides − many of whom rose to prominent positions after serving as fighters in armed groups − used violence as a tool for resolving their differences. The 2011 violence should also be placed in the broader context of Burundi's prolonged civil war which ended in 2009, as some of the current political tensions originate from that conflict.

Burundi's recent history, including the past two years, has been tarnished by political violence, notwithstanding reforms and improvements in other areas.[1] Despite moves toward multi-party democracy since 2005, many politicians, aspiring politicians, and former combatants continue to speak and act as if violence was the only avenue for gaining political power.

The assassination of democratically elected President Melchior Ndadaye − a Hutu − in 1993 sparked a civil war that followed mainly ethnic lines between the Tutsi-dominated army and the majority Hutu rebels. The conflict claimed tens of thousands of civilian lives. The largest rebel movement, the CNDD-FDD, entered into a formal ceasefire in 2003 and won the 2005 elections. The other principal rebel group, the FNL, remained outside this political process.[2]

The civil war ended in 2009 with the transformation of the FNL from an armed group to a political party. Elections were set for 2010, and the two groups began a contest for the country’s majority Hutu vote that often led to violence.[3] While other parties also contested the elections, the CNDD-FDD and the FNL were the main players. The four-month long elections cycle started at the level of communes[4] on May 24, 2010. The National Independent Electoral Commission announced provisional results on May 25, giving the CNDD-FDD a large lead over the FNL. Electoral code violations were reported in isolated areas, and the opposition quickly denounced the results.[5] In June, 12 opposition parties formed a coalition, the Alliance of Democrats for Change (Alliance des démocrates pour le changement, ADC-Ikibiri), and called for new communal elections. The ADC-Ikibiri subsequently boycotted the remainder of the electoral calendar. Foreign governments and diplomats, prioritizing stability over voting irregularities, maintained that the elections were free and fair and criticized the opposition boycott. Burundian civil society organizations which observed the elections, as well as international election monitors, noted some electoral irregularities but maintained that these would not have affected the election results in a significant way.

Following the 2010 elections, the CNDD-FDD maintained a near total monopoly of power. Not content with this, the party then engaged in political maneuvering to infiltrate and weaken its political rivals, notably the FNL. In July 2010 the CNDD-FDD offered some FNL leaders government positions if they agreed to choose a different leadership for their party and re-joined the political process. A few supported this option but most opposed it. In August 2010 a handful of FNL leaders held an “extraordinary congress” and voted out the FNL leadership, in violation of party rules. The government, through the minister of the interior, officially recognized this new leadership a few days later.[6] “Ousted” FNL president Agathon Rwasa suggested the possibility of a return to violence in the absence of a resolution to this stalemate.[7]

On June 15, 2010, the police surrounded Rwasa’s house. Although they did not attempt to arrest him, a week later, he chose to go into hiding and later fled the country. A number of other opposition party leaders also went into exile. As Rwasa left the country, there were reports of FNL elements returning to their strongholds along the Congolese border and taking up arms again. By the second half of 2010 the security situation in Burundi was deteriorating, particularly in the provinces along the border with the DRC and those regarded as FNL fiefdoms.[8] State security forces started to target former FNL combatants. In September and October 2010, mutilated bodies were found in the Rukoko forest and in the Rusizi river; some of the victims were identified as former FNL members who had integrated into the national security forces and had subsequently deserted.

It is against this backdrop that political killings escalated sharply from the end of 2010.

II. Patterns of Political Violence in 2011

Incidents of political violence in late 2010 and throughout 2011 have followed several distinct patterns. Three main categories of killings have emerged: killings in which members of opposition groups have been targeted (notably the FNL); killings in which members of the ruling CNDD-FDD have been targeted; and larger-scale attacks by armed gunmen in which the majority of victims had no known political affiliation. Attacks in the first two categories were often reciprocal: killings of members of one party have been swiftly followed by killings of members of the opposing party in a cycle of reprisal and revenge.

The majority of incidents documented by Human Rights Watch occurred in Bujumbura Mairie and Bujumbura Rural provinces. Both are considered political strongholds of the FNL, making them especially prone to attacks. There was also heightened tension in these areas between the population and the youth wing of the CNDD-FDD, the Imbonerakure (see below). Human Rights Watch documented several killings in the second half of 2011 in other areas, including in the provinces of Gitega and Kayanza. In some cases, it was difficult to confirm the location where the victims had been killed, as their bodies were found far away from where they were last seen or where they were abducted.

While the violence in Burundi was unrelenting from late 2010 to late 2011, Human Rights Watch found that attacks on members of the opposition intensified between July and October 2011. The increase in the number of murders of FNL members or former members during this period was striking, with killings sometimes reported on a weekly or even daily basis. Moreover, many of the individuals associated with the FNL who were killed during this period were higher-ranking FNL members, including former political representatives and commanders. One of the most notorious cases was that of Edouard Ruvayanga, a former FNL commander who had joined the national police, then deserted. Once close to Agathon Rwasa, he reportedly continued to play a leading role in the armed opposition and was widely believed by those interviewed by Human Rights Watch to be behind many killings in Bujumbura Rural in 2011.[9] Ruvayanga was killed in September 2011. In contrast, most of those killed in previous months had been lower-ranking FNL members or former members. Similarly, most of the CNDD-FDD members who were killed were low-level local officials.

The manner in which political killings, especially those committed by state agents, were carried out in 2011 − for example multiple shots or stabbings, mutilation and disfigurement − became increasingly brutal, demonstrating a desire for vengeance. Indeed, Burundians often used the term “hatred” to describe these acts.[10] The gratuitously violent nature of these killings appeared to be a deliberate tactic designed to spread fear. Several cases covered in more detail in other sections of this report offer a graphic illustration. For example Dédith Niyirera, an FNL representative in Kayanza province, was shot between 30 and 50 times at close range. Oscar Nibitanga, a former FNL combatant who had refused to collaborate with the intelligence services, was shot multiple times in the head; a witness who saw his dead body described it as one whose “face had been destroyed.”[11] Léandre Bukuru, a member of the MSD, was decapitated and his head found in a separate location from his body.

Finally, throughout 2011 Human Rights Watch noted a troubling pattern in which former FNL combatants who had demobilized, either through official channels or acting on their own will, were subjected to intense pressure to join the Imbonerakure or the intelligence services (Service national de renseignement, SNR). Those who refused were threatened with death; several who tried to resist the pressure paid with their lives. Many more were forced to go into hiding.

Reprisal Killings“It’s an eye for an eye [...] If one FNL is killed, one CNDD-FDD is killed. If two FNL are killed, two CNDD-FDD are killed. It’s the balance of terror.”[12] The tit-for-tat nature of killings sometimes led to people affiliated with different political parties being killed on the same day in the same locality. For instance, on April 16, 2011, Jeanine Ndayishimiye, a woman in her 20s who was the sister of a CNDD-FDD member, was shot dead in her home in zone Kiyenzi, Kanyosha, Bujumbura Rural, by armed men who some witnesses claimed were local FNL members. The perpetrators said they were looking for her brother and demanded money.[13] One of her relatives, an active member of the CNDD-FDD, received a call from one of her killers on the night of her death. He told Human Rights Watch: After [she] was killed, they called me on the phone to say that if they catch me, they will kill me. They called me the same evening, at about 9 p.m. They said “even if you've escaped, we will catch you. Come and bury [her]. I've just killed her” and hung up. I didn't know she had died. They told me themselves they had killed her.[14] He recognized the caller’s voice as that of an FNL member from the same area. When he told him on the phone that he recognized his voice, the man replied, “We'll start by eliminating you. Then there will be no one left to take revenge.”[15] Later that evening, Arthémon Manirakiza,[16] a neighbor of Jeanine Ndayishimiye and a former member of the FNL youth wing, was also murdered. Armed men in military uniform went to his house and assembled the family outside. They asked Manirakiza’s family “what do you know about the killing which just occurred?” His relatives said they did not know anything as they had been at home. The men said “you are hiding those who killed that person.” They accused Manirakiza of being a combatant and demanded to see him, claiming that they were going to make him show them “where the killers went” (alluding to the killing of Ndayishimiye). They forced Manirakiza out of the house and led him away with his arms behind his back. Neighbors told family members that they heard him screaming that he had nothing to do with the earlier killing and that he had been at home all night. Shortly afterwards, many shots were fired. Manirakiza’s body was found the next day.[17] These reciprocal attacks have instilled fear among the local population. Each killing is expected to trigger another. As one Bujumbura resident told Human Rights Watch in early 2011, “We are powerless. There are reprisal attacks. One night, a CNDD-FDD is killed, the next night an FNL is killed.”[18] |

The Imbonerakure [19]The use of youth groups has long been a feature of the operation of political parties in Burundi. In late 2008 the CNDD-FDD mobilized youth throughout the country into quasi-military groups in order to demonstrate their strength. These groups came to be known as the Imbonerakure (translated from Kirundi as “those who see far into the distance”). The CNDD-FDD used the Imbonerakure from 2009 into the electoral period of 2010 to intimidate and harass the political opposition, often engaging in open street fights with other parties’ youth wings, notably the FNL’s Ivyumavyindenge (roughtly translated from Kirundi as “those built as strong as airplanes”, formerly the Hutu Patriotic Youth (Jeunesse Patriotique Hutu, JPH). The reliance on youth to intimidate and attack perceived opponents at local levels is still visible in the political violence in Burundi today. The Imbonerakure often operate at the local level. It is not always clear whether senior government or party officials have planned or ordered the actions of individual members. However, their overall patterns of behavior, illustrated in this report, demonstrate a striking confidence in targeting perceived opponents of the ruling party, and they have consistently been shielded from justice. At the local levels, members of the Imbonerakure and the intelligence services appeared to cooperate in intimidation and attacks, which may indicate state involvement and interest in backing their actions. In 2011, members of the Imbonerakure frequently harassed and threatened former FNL members, sometimes jointly with members of the state intelligence services, and carried out attacks. Some of the Imbonerakure carried firearms. Many former or current FNL members told Human Rights Watch researchers that the majority of threats they received came from members of the Imbonerakure, sometimes from individuals they knew personally. In certain areas, especially where the FNL has strong public support, residents have reported seeing Imbonerakure patrolling at night and chanting CNDD-FDD songs. Some reported seeing them carrying weapons. A resident of Ruziba, Kanyosha Urbain (an area of Bujumbura where there were several political killings in 2011) stated: The Imbonerakure had been given arms and were looking for “people who create insecurity” [which really means] people who are not from their party. In reality, they were just harassing ex-FNL members, taking money from them or even killing them. They do nocturnal patrols from about 6 p.m. We have seen them with arms. We know them as they live around here. There are more than ten of them here [...] The Imbonerakure say “all those who fought for the FNL will have problems.” They say this to people face to face.[20] In one instance, local residents claimed that members of the Imbonerakure were allegedly involved in the murder of a child whose parents had been FNL members, and they denounced the Imbonerakure on the radio (see case of Wilson Ndayishimiye in Section III). These local residents were then harassed and threatened by members of the Imbonerakure. One of the Imbonerakure warned the relative of an individual who had denounced them on the radio: “Tell him he has dug his own grave and he will go into it.”[21] |

III. Killings of FNL and Former FNL Members

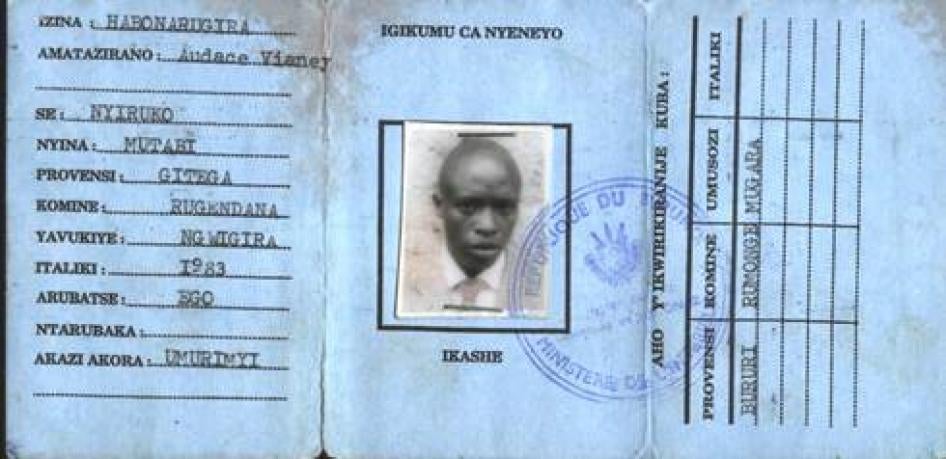

The Killing of Audace Vianney Habonarugira

Identity card of Audace Vianney Habonarugira. ©2011 Private

Audace Vianney Habonarugira, a demobilized FNL commander, was killed in July 2011. A near-fatal shooting in March 2011 and a series of threats against him by members of the intelligence services and security forces indicate that state agents may have been responsible for his death.

While many FNL and former FNL members had been killed in the preceding months, Habonarugira was the first of several higher-ranking former FNL commanders killed between July and October 2011, signaling a renewed determination by security forces to further weaken the movement and frighten any remaining sympathizers into joining the ruling party.[22]

Habonarugira was 28 years old, married and had a two-year-old child. He had joined the FNL in the 1990s, when he was still a boy. He eventually reached the rank of colonel, before deciding to leave the movement in June 2009. He then went through the official demobilization process, retrained as a driver and mechanic, found work and resumed civilian life. However, like so many other demobilized FNL members, he was never able to shed his affiliation with his former movement. From January 2011 until his death six months later, he was repeatedly threatened and hunted down by the police and intelligence services.

One week before his death, Habonarugira, in an interview with Human Rights Watch, described the sequence of events in the weeks preceding his near-fatal shooting in March 2011, and the subsequent threats which would ultimately lead to his death.[23]

Habonarugira told Human Rights Watch that Cyrille Nahimana − variously described as a policeman and an intelligence agent[24]− began threatening him in January 2011, and that he first met Nahimana − whom he simply called “Cyrille”[25] − on January 22, following the arrest of another demobilized FNL commander in Kamenge, the neighborhood of Bujumbura where Habonarugira lived. Three days later, according to Habonarugira, Nahimana sent an intermediary to see him at home. The intermediary told him that as a former FNL colonel, Habonarugira should immediately report to the intelligence services. Habonarugira did not do so. In mid-February, Habonarugira saw Nahimana again. This time, Nahimana introduced himself as a friend of three senior police and intelligence officers (whom he named) and tried to entice Habonarugira to join them by promising him work. He offered to pay Habonarugira if he gave him the names of other FNL leaders. Habonarugira refused.[26]

On February 27, according to Habonarugira’s account, Nahimana called him and asked where he was at that moment. Suspecting a trap, Habonarugira gave a false address and sent a friend to meet him instead. When the friend arrived at the appointed place, he found a truck belonging to the intelligence services with five policemen, together with a former FNL member who had joined the intelligence services. They started beating and kicking the friend, until he told them that he was not Habonarugira. They then let him go. Habonarugira said his friend’s arm was swollen from the beatings. Nahimana himself was not in the vehicle, but was nearby, and intervened to tell the policemen they had the wrong person. The friend told Habonarugira that he believed they would have killed Habonarugira had he gone there himself.[27]

On March 7, Nahimana and three other men came to Habonarugira’s house. Habonarugira told Human Rights Watch:

In the early morning, when I went to wash outside, I saw some people coming. They grabbed me by both arms. It was Cyrille [Nahimana] and three others I didn’t recognize. Cyrille brought out a gun which he loaded in front of me. He said: “We offered you work, but you refused. Now we have been given the task of taking your corpse to our bosses. We will not take you there alive. We will take you there dead.” They took me away, on foot. When we were about 100 metres from my house, Cyrille said: “I am going to kill you and they will even forget your name in this country.” He gave orders to a policeman who shot me in the leg. Then the same policeman shot three bullets at me, on each side, here [at the level of the hip] and in the stomach. One bullet went right through. I fell and lost consciousness.[28]

Habonarugira was gravely injured. He was initially in a coma and was hospitalized in Bujumbura for three and a half months. For the first month, until April 19, he was under police guard at the hospital. He said that individuals whom he believed were intelligence agents came to the hospital and gave instructions to his police guard and to the hospital staff to let them know if he left. One witness stated that Nahimana himself was seen outside the hospital several times, but did not enter the hospital.[29]

On the day Habonarugira was shot, the police arrested his wife and several neighbors and accused them of collaborating with Habonarugira, whom they described as a criminal. They were released four days later, without charge.[30]

Habonarugira was discharged from hospital on June 27. From then on, he was hunted from province to province, first in Rumonge (about 80 kilometers from Bujumbura), then in Gitega (about 110 kilometers from Bujumbura); in both locations, he had gone to stay with family members. Habonarugira recounted how in Rumonge, a local government official came to his relatives’ house to check if he was there, asking for him by name. Habonarugira pretended that it was not him, and the official, who did not recognize him, left. Neighbors told Habonarugira that they had seen vehicles belonging to the intelligence services at the local official’s house. Habonarugira fled to Gitega province. He arrived there at around 10 a.m. By 8 p.m. the same day, the police and military had already come looking for him. Not recognizing him, a soldier asked Habonarugira whether he knew “Habonarugira Audace Vianney, an FNL colonel” because they wanted to know what he was doing there and how he got out of hospital. Habonarugira left immediately and returned to Bujumbura, where he went into hiding.

Human Rights Watch researchers met him six days later. He was still recovering from the injuries he had sustained in March, which had left him with extensive scars on his stomach. Although he was in hiding, he said he wanted his case to be known: “You can talk about it,” he told Human Rights Watch, “I am not afraid.”[31]

Audace Vianney Habonarugira’s injuries in July 2011, four months after he was shot in March 2011. ©2011 Human Rights Watch

Six days later, on July 15, his dead body was found, alongside that of another man, at Gasamanzuki, in Isare commune, Bujumbura Rural province. The second victim was Claude Kwizera, believed to be a demobilized FNL combatant and a close friend of Habonarugira. Both men had gunshot wounds. The previous evening, local residents in the area where the bodies were found had seen a truck arrive from the direction of Bujumbura, from which several men got out and climbed a hill nearby. They reported that several of these men were armed, and that some were wearing police or military uniforms. The residents later heard a commotion and gun shots.[32] Local people found the two bodies the next morning.

The circumstances in which the two men were killed are not clear. According to sources close to Habonarugira, on July 14, at around 3 p.m. he received a phone-call from a friend asking him to go to Bujumbura to collect some money he was owed. He was afraid, but went anyway. At about 6 p.m. he called his family to inform them that the person who called earlier was an imposter, not his creditor. Sources told Human Rights Watch that in the course of that telephone conversation with Habonarugira, they heard a voice in the background saying “take the phone!” and the call was cut off. That was the last his family heard of him. His relatives tried to call him back throughout the night but his phone had been switched off.[33]

Habonarugira’s case illustrates the intense pressure exerted on former FNL members to cooperate with the intelligence services. They have been asked to identify and denounce their former comrades, and they risk being killed if they refuse. It also demonstrates the failure of the demobilization process: former FNL members are forever tainted by their past associations and are not allowed to resume a normal civilian life, even after they have resolved to give up armed activities. The day before he was shot in March 2011, Habonarugira had confided to people close to him that he was afraid of what would happen to him because he had refused to identify former FNL combatants for the intelligence services. He said he was not interested in cooperating with the intelligence services because he was tired of war, and that even if he had accepted, the FNL would probably have killed him for betraying them.[34]

On July 20, the prosecutor of Bujumbura Mairie told Human Rights Watch that he had set up a commission of inquiry to investigate Habonarugira’s case and four others. The commission, which was set up before Habonarugira was killed, initially focused on the incident in which Nahimana had shot Habonarugira in March. Habonarugira testified to the commission a few days before his death.[35] According to official investigations, Nahimana admitted shooting Habonarugira in March, but claimed it was in legitimate self-defense, as Habonarugira had allegedly resisted a police search of his house. The police claimed that they found grenades, cartridges, and military clothing in his house.[36] The prosecutor general confirmed that a casefile on the shooting in March had been opened and that Nahimana was accused of the attempted murder of Habonarugira, but that he had not been arrested; he claimed that the murder suspects had not yet been identified.[37] At the time of writing the investigations into Habonarugira’s death had not progressed and Nahimana had still not been arrested.[38]

The Killing of Dédith Niyirera

Dédith Niyirera, a former FNL representative, was killed in Kayanza on August 27, 2011. In the period leading up to his death, SNR agents had repeatedly warned him that if he did not join the CNDD-FDD, he would be killed.

Niyirera was a former member of the CNDD-FDD and had fought for them as a teenager, when they were still a rebel group. After joining their political wing, he held an administrative post in his home village of Butaganzwa. Niyirera left the CNDD-FDD in 2007 to join the FNL. While his reasons for switching allegiance were unclear, he explained to a family member that he was happy he had left the CNDD-FDD because they “killed many people”.[39] After joining the FNL he was promoted to the position of executive secretary for Kayanza province. Niyirera was well educated and worked as a secondary school teacher.

After leaving the CNDD-FDD, he was harassed and threatened. He was upset by the CNDD-FDD victory in the 2010 elections and informed sources told Human Rights Watch that he used to say he felt that the elections had been stolen from the FNL.[40]

In October 2010 Niyirera was arrested by the SNR in Kayanza. The arresting officer told him that it was “because of the insecurity. You work for armed groups and you are training with rebels”.[41] He was transferred to Bujumbura and spent at least two weeks in SNR custody. He was never brought before a court. Instead, SNR agents accused him of being part of a rebellion and tried to convince him to re-join the CNDD-FDD and to renounce the FNL. They told him, “We are not going to hurt you because we are going to free you. You will join the CNDD-FDD. You are smart. You went to university. You will return to Kayanza and convince others to quit the FNL.”[42] Niyirera refused to collaborate with the SNR but was released. He returned to Kayanza and the threats against him increased.

By 2011 the FNL’s regional headquarters in Kayanza had closed and the party’s political activities had all but ceased. In July 2011 Niyirera told other FNL members, “We should leave politics so we can be left in peace.”[43]

In mid-2011 there were rumors in Kayanza of a list circulating with the names of FNL members who were to be killed. Shortly before Niyirera’s death, the governor of Kayanza, a former friend and member of the CNDD-FDD, told him, “You go back to the CNDD-FDD. You are smart. We will give you money and things. You need to join us.”[44] Niyirera replied: “I know there is a list of 10 people to be killed and I am at the top.” In the weeks before his death Niyirera received threatening phone calls. The night before he was killed, an anonymous caller told him on the phone, “if you do not leave, you will see what will happen.”[45] The same night, he told a friend how the head of the SNR in Kayanza had told him “you will not have peace while you are living.”[46] By August 2011 he barely left his house and told his family that he was sure he would be killed soon.[47]

On the afternoon of August 27, Niyirera left his home to go to town. At around 7 p.m. he returned home alone. Approximately 300 meters from his house, he was ambushed by gunmen who were waiting for him. His wife and two children were at home and heard the shots. His neighbors who were aware of the threats Niyirera had faced said they guessed the shots were intended to kill him. As someone close to the family said: “When I heard the shooting at 7 p.m. I instantly knew it was him”.[48] A family friend who saw the corpse the next day told Human Rights Watch that Niyirera had been shot more than 30 times.[49]

The prosecutor of Kayanza told Human Rights Watch that judicial officials had tried to investigate Niyirera’s death but had been unable to open a casefile by January 2012 because of lack of witness testimony. He claimed that there were no witnesses because the incident had occurred at night. He said judicial officials had met FNL members, as well as local residents, about the case but they had not provided any information.[50]

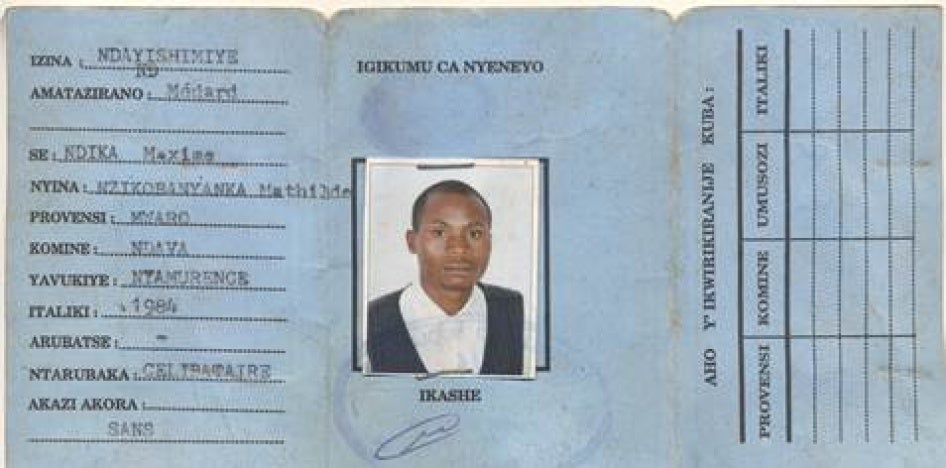

The Killing of Médard Ndayishimiye

Identity card of Médard Ndayishimiye. ©2011 Private

Like the killing of Audace Vianney Habonarugira, the assassination of Médard Ndayishimiye demonstrates a pattern of state agents hunting FNL members across the country. It also highlights the targeting of leaders and “intellectuals” within the party.[51]

Ndayishimiye was 27 when he was killed. He became an active member of the FNL when he was still a student. In 2009 he became the head of the FNL in his home commune of Ndava in Mwaro province. During the 2010 elections he was very active in the party and caught the attention of local CNDD-FDD officials.[52]

In February 2011 he was involved in a public fight with an army colonel, reportedly over a political matter. A crowd gathered and many people witnessed the fight. The colonel was reported to have said “we will see the consequences of this fight.”[53]

Ndayishimiye had also had arguments with a demobilized CNDD-FDD member from Ndava, Bernard Bigingo. Since his demobilization, Bigingo was reported to work at the CNDD-FDD headquarters in Bujumbura and was believed to collaborate with the SNR.[54] A former local government official told Human Rights Watch that he had been informed that Bigingo was openly preparing to go into the countryside to hunt down FNL members and would say “we are going to finish with these people from the FNL.”[55] Bigingo is reported to have used members of the Imbonerakure to track former FNL members and to keep him abreast of their movements.[56]

In June 2011 the police commissioner of Mwaro, accompanied by around 20 armed policemen, arrived at Ndayishimiye’s home. They surrounded the house in order to prevent anyone from leaving. The next day the police searched the house. They accused his family of sheltering criminals and Ndayishimiye of possessing arms in order to help FNL rebels. The police did not find any weapons or other incriminating items in the house; they just found two FNL flags. Nevertheless, the commissioner again accused Ndayishimiye of transporting arms and supporting rebels. The police had a document which they claimed was an arrest warrant but the family was not allowed to read it. The commissioner left saying, “Even though we haven't found what we're looking for, be careful and don't shelter anyone who is not from here. The arrest warrant comes from the highest authority in Bujumbura.”[57]

On July 6, 2011, the same commissioner again sent the local police officers from Kibimba and Nyamulenge to Ndayishimiye’s home with a group of policemen in order to search the house for guns. They came to arrest Ndayishimiye, but he was away in Gitega at the time.[58]

On the night of August 3, 2011, soldiers from Mwaro based near the Mpanuka parish came to Ndayishimiye’s home at around 2 a.m. They knocked on the door shouting “open and come out! If not, you may die.” A family member opened the door. They asked him “where is Médard?” Despite being told that he was away visiting a friend, the soldiers went into the house looking for him.[59]

After this latest attempt to find him, Ndayishimiye decided to flee Mwaro.[60] He moved to Gitega and found work as an electrician at a local hotel.

On October 6, 2011, Ndayishimiye was returning home from work on a bicycle taxi, as he did every day. On the outskirts of the town of Gitega, near the airstrip, a jeep with tinted windows pulled up quickly in front of the bicycle. Unidentified men exited the vehicle and beat both Ndayishimiye and the bicycle driver, then forced Ndayishimiye into the back of the jeep.[61] His friends and family tried to find out where he had been taken but were afraid to go to the police as they felt the police may have been involved in his abduction.[62]

The next day Ndayishimiye’s body was found in Rutana province, about 120 kilometers from Gitega. Marks on his body indicated that he may have been tortured. He had several knife cuts on his chest and throat, and he had been stabbed repeatedly in or near his heart. People who saw the corpse noted rope marks around his neck.[63]

Ndayishimiye’s friends and family told Human Rights Watch they were afraid of demanding justice for his murder and felt they had no real avenue for recourse, especially as some of them were also associated with the FNL. As one friend of the family told Human Rights Watch, “We don't dare ask questions because we're FNL and we're scared of being arrested. Witnesses are afraid. There is no investigation. No one has interviewed the family. Nothing.”[64]

Because of Ndayishimiye’s affiliation with the FNL and the circumstances surrounding his death, neighbors were reluctant to participate in the mourning ceremony, an important ritual in Burundian culture, because they thought they might be perceived as criminals.[65] A family friend who had spoken out about the killing of Ndayishimiye’s murder was warned by a police investigator to be careful. He was asked to “go slowly, it's a delicate case, don't talk too much about it.”[66]

The Killing of Oscar Nibitanga

Oscar Nibitanga was found dead on August 16, 2011 in Mutimbuzi commune in Bujumbura Rural. He was a teenager when he joined the FNL, shortly before the FNL was due to sign the 2009 peace accords. Some of his close friends believed that like many others, he joined in order to obtain a position in the national army.[67] Nibitanga was indeed integrated into the army after the ceasefire, but he was not satisfied with his rank. As someone with a secondary school diploma, he believed the position offered to him was not sufficient.[68] He decided to leave the army and returned to study at a local university in Bujumbura.

As part of the admission process, Nibitanga was required to produce documentation from the state that he was in good standing with the government. He received this attestation in August 2010.[69]

In June 2011 Nibitanga was arrested in Bubanza and detained for one month. He was released without trial. According to local press accounts, he was initially detained by SNR agents on the basis that he had been distributing arms to criminals. This charge was later changed to participation in the assassination of a police officer.[70] He returned to Bujumbura to continue his studies.

Shortly after his release, a former FNL combatant known as Jimmy started pressurizing him to join CNDD-FDD.[71] Jimmy had been in the FNL with Nibitanga and had since joined the SNR. He had passed by Nibitanga’s home in Bubanza and told one of Nibitanga's relatives: “Advise him, there are investigations that we are doing. There is information we have. If he comes himself, there will be no problem, but if he does not, there will be problems.”[72] Jimmy was more straightforward with Nibitanga himself. In the summer of 2011, he took Nibitanga and a friend out for drinks and told him directly, “If you do not join the SNR, we will kill you.” Nibitanga accepted to join them, but only to get out of the conversation.[73] He later told a confidant that he could not accept to identify former FNL members in Bubanza because they were his friends.[74] Just before Nibitanga's death, Jimmy was calling him up to four times a day.[75]

On August 15 at about 8 p.m. while Nibitanga was studying at home, two men entered his house without knocking. Local residents identified one of them as an SNR agent nicknamed Numéro who operates in Bujumbura.[76] Numéro and his partner introduced themselves as SNR, and claimed that Nibitanga knew where FNL leader Agathon Rwasa was hiding when he was in Bujumbura and where the FNL kept arms caches in town. Nibitanga denied this. After searching the house they took him away in a vehicle identified by neighbors as an SNR vehicle. Nibitanga’s last words were “pray for me.”[77]

The next day his body was found in Mutimbuzi commune, wearing the same clothes he had last been seen in the night before. Officials on the scene hurriedly buried the body and told family members “we could not leave the body, and given the manner in which he was killed, it is better you do not see it. It was scandalous, the hatred with which he was killed.”[78]

Local authorities initially refused to allow the family to exhume the remains. However, eventually, the family was allowed to exhume and rebury the body in a proper cemetery. Nibitanga’s father died soon afterwards, in September. Relatives told Human Rights Watch that he was so consumed with grief over his son’s death that he refused to eat.[79]

Shortly before his death Nibitanga told a close acquaintance that Jimmy had offered him 250,000 Burundian francs (around US$185) to reveal where arms were hidden and 50,000 Burundian francs (around US$37) to identify former FNL members, but Nibitanga maintained he would “rather die than denounce people.”[80]

At the time of writing, there has been no official inquiry into Nibitanga’s murder. Human Rights Watch spoke with judicial authorities on three occasions to inquire about progress on this case but the authorities could not find his casefile, despite the high-profile nature of this killing and coverage in the national media.[81]

Killings of Other FNL and Former FNL Members

Human Rights Watch has collected firsthand statements on scores of other cases of killings of current and former FNL members by forces aligned with the CNDD-FDD. The cases are too numerous to list in this report. Among them are those summarized below, all of which Human Rights Watch has researched in detail.

- Pasteur Mpaganje, nicknamed Giswi, was killed at his home in Ruziba, Bujumbura in late February 2011. Mpaganje, a 39-year-old father of five, was known as an FNL member in his local community. He had attended FNL meetings in Kanyosha around the time of the 2010 elections. People in his area believed to be sympathizers of the CNDD-FDD used to point at him and mock him for being an FNL member, but he did not take these threats seriously. On the evening of his death, neighbors saw members of the Imbonerakure following him home. Several shots were fired. It is not clear whether he was shot inside or outside the house. His body was found in the front room of his house, propped up against the wall.[82] According to prosecuting officials in September 2011, a casefile had been opened, but no arrests had been made.[83]

- Célestin Mwina, a businessman and member of the FNL in his fifties, was killed by gunmen on May 25, 2011, in Kajiji commune, Bujumbura Rural. He had been the president of the FNL at the local level of colline Musugi. Since the 2010 elections CNDD-FDD members had pressured him to join their party and warned him: “If you don’t quit the FNL we will eliminate you.” Mwina ran a small kiosk. When he left work on the afternoon of May 25, witnesses noticed four or five members of the Imbonerakure following him. Mwina was shot several times as he was approaching his house and died on the spot. Neighbors overheard part of the conversation between Mwina and his killers. The men reportedly asked him whether he was Mwina Célestin and said “you don't want to leave the FNL?” before shooting him. After his death, individuals close to Mwina who spoke about his killing on the radio were threatened. They received anonymous calls saying “the information you gave, we heard it, we will ensure that you follow Célestin” and “any time now we are going to come and eliminate you all.”[84]

- Wilson Ndayishimiye was the four-year-old son of two FNL members. He was shot dead while sleeping at his house in Ruziba, Bujumbura, on May 17, 2011. Wilson’s father, a demobilized FNL combatant, had previously been asked to join the Imbonerakure on their nightly patrols but had refused. In the days leading up to May 17, Imbonerakure, some of whom were armed, were seen patrolling the neighborhood. In the evening, after the family had gone to bed, gunmen shot through the air vents above the door and windows of the house, hitting the side of Wilson’s body. His two older brothers were sleeping next to him, but neither of them was injured. The family suspects that the boy’s father may have been the real target since he had refused to join the Imbonerakure. The house had been attacked at least once before, around January 2011; gunmen had shot at the house but no one had been injured on that occasion.[85]

A Clandestine Life: FNL and Former FNL Members in Hiding

With the increase in targeted attacks on FNL members and former combatants, many individuals associated with the group have been forced into hiding. Some of them have continued to receive threatening phone calls or messages in their hiding places, indicating that in some cases, the intelligence services were aware of their whereabouts. Furthermore, because the SNR has successfully co-opted former FNL members into its ranks to help identify other FNL members, many of these people no longer even trust their former colleagues. A demobilized FNL combatant told Human Rights Watch, “We don't talk among ourselves anymore. We don't trust each other as some could talk to the intelligence services. From the moment you are not with them [the CNDD-FDD], you are targeted.”[86]

The case of former FNL commander Audace Vianney Habonarugira (described above), who was killed just a few days after being coaxed out of hiding, was cited by other former FNL members as an example of why they could no longer trust anybody. When asked if he could go to the police for protection, one former FNL combatant in hiding told Human Rights Watch to “look at what they did to Audace Vianney [Habonarugira]. He went to the police first and then he was killed.”[87] Another former FNL member in hiding was approached by a man who pretended to be at risk and befriended him. The former FNL member realized he was being tricked when the man tried to lure him out of his hiding place and to persuade him to go and talk to the intelligence services.[88]

Some people have gone into hiding to evade specific individuals. A former FNL combatant who agreed to speak to Human Rights Watch was in hiding in Bujumbura in an attempt to avoid two individuals known as Numéro and Kazungu, believed to be working for the SNR. Both men have been linked to killings of people associated with the opposition.[89] This former combatant had been pressured by the Imbonerakure to join their group before the 2010 elections and threatened with death if he refused. Later in 2010 he was arrested and threatened with death again if he did not join the Imbonerakure. In late 2011 he told Human Rights Watch, “They are not looking for me to join the SNR or the Imbonerakure anymore. They want me to die.” When Human Rights Watch was last in contact with him, he had moved to a neighborhood where he was not known and had spent many nights sleeping in the hills outside of Bujumbura.[90] The police set up check points in his new neighborhood and were asking people if they knew him. As he was living under a false name, he managed to evade capture.

The CNIDH showed significant courage in sheltering five former FNL members and combatants in its office from the end of August 2011. While this helped give public exposure to the insecurity facing people associated with the FNL, it created a dilemma in that these men were effectively stuck at the CNIDH for several months.[91] State institutions, including the police and the SNR, sent senior representatives to try to coax them out of the office, to no avail: these five individuals rejected the authorities’ assurances of safety and refused to leave the CNIDH, believing that leaving would mean certain death.[92] Eventually, one of them left in late December 2011. By early February 2012, the other four had also left after the CNIDH told them they could not stay there indefinitely.[93]

Not all those in hiding are former combatants. In late November and early December 2011 seven supposed members of the FNL were arrested by the police in Karuzi. A local resident who spoke to Human Rights Watch was at home on the morning of December 2 when he received a phone call from friends informing him the police were looking for him. He had heard the news of the seven arrests on the radio, and as a former FNL member himself, he felt he was in danger. Rather than wait for the police to arrest him he fled to the bush and spent two days in hiding. His friends told him that the police were waiting for him at his home. The police told one of his relatives: “If you do not tell us where he is, we will put you in prison.” After two days in the bush, he walked to the next town, then travelled to Bujumbura where he remained until mid-February 2012; he then fled the country.[94]

Some former FNL members are caught between two worlds, one in which they are hiding from forces aligned with the CNDD-FDD and another in which they are trying to live a normal life as productive members of society. Human Rights Watch met a former FNL member who had served for 15 months as a senior provincial government official. Despite his former high-ranking position and the fact that he had quit politics, he continued to be hunted by SNR agents. From October 2011 he started to notice he was routinely followed by individuals in government cars on his way to and from work. Friends told him that high ranking members of the SNR would speak about his death openly. In October 2011 friends heard one high ranking SNR member say, “We are going to follow him and we will abduct him when he is alone”. This former FNL member eventually went into hiding.[95]

Going into hiding is an emergency measure for those who believe they are at risk, but it provides no guarantee of security and is not sustainable in the long term. Almost all the people in hiding who spoke to Human Rights Watch had one simple aim: to leave the country. For them, the extent of persecution by state agents has made it impossible to peacefully reintegrate into society. Police and SNR agents often stopped by the homes of their families and tried to persuade their relatives to coax them out of hiding. However, no amount of reassurance or persuasion by these agents would convince them to return home. They felt unable to turn to the police for protection in view of the involvement of the police in political killings and other human rights abuses, and the close relationship between the police and the SNR. A former FNL combatant described to Human Rights Watch how he was walking along the road when he was suddenly chased by Imbonerakure.[96] Another described how he was chased through a neighborhood and shot at by members of the SNR.[97]

IV. Killing of Members of Other Opposition Parties

While the majority of victims of political killings attributed to state agents or ruling party members were current or former FNL members, members of other political parties have also been targeted, sometimes along similar patterns.

The Killing of Jean-Bosco Bugingo

On December 2, 2010, Jean-Bosco Bugingo, a chef de zone (local official) and a member of the FRODEBU party in Kiyenzi, commune Kanyosha, Bujumbura Rural, was killed by armed men at his home in Ruziba, Bujumbura Mairie. He was 31 years old and had three young children.

Shortly after Bugingo became a local official for FRODEBU in 2005, he began receiving threats from CNDD-FDD members telling him to leave his party. According to a person close to Bugingo, a local CNDD-FDD member would insult and spit at Bugingo, saying “you're not one of us. You don't belong to us.”[98] In 2008 Bugingo moved house following anonymous telephone threats and when he noticed that unknown individuals would show up outside his house.[99]

But moving to another house offered him no protection from those who seemed determined to kill him. On the night of December 2, 2010, Bugingo stepped out of his house to investigate the presence of intruders in his compound. Witnesses reported hearing several shots and Bugingo screaming. He was injured on the neck and the side, and died before he could be taken to hospital.[100] Another individual, identified simply by his first name Egide, was also found dead in Bugingo’s compound. Local residents described Egide as a member of the Imbonerakure and the circumstances surrounding his death remain unclear.

After Bugingo's death, several anonymous written messages and letters were found at his local office warning that if he did not leave his party and join the CNDD-FDD, his family would suffer. Indeed, several members of his family were threatened in the weeks following his death.[101]The last letter that was found bore the following message, written by hand in Kirundi:[102]

To the chef de zone

We are writing to you to tell you one last time what we have told you several times before, that you have to change your political party FRODEBU of Léonce [Ngendakumana, the president of FRODEBU] to come and join the CNDD-FDD party. You refused, and we gave you five years, and now, these five years have ended without you changing your political party. We waited several times for you to change, but you refused. So what do you think?? This year will not end with you still being chef de zone of Kiyenzi. There are others who need to be chiefs of this zone, your home and your family will lose out, but there is no shortage of leaders in this country. A word to the wise is enough. This letter is the very last and this year will not end without something happening [to you], or else to your family.

Ok ok ok.

It is not good to tell you who we are.

Thank you.

The Killing of Cheikh Congera Hamza

Cheikh Congera Hamza was a respected member of the Muslim community in Bujumbura and member of the opposition party Union for Peace and Development (Union pour la paix et le développement, UPD). He was shot dead in the early hours of December 9, 2010 on his way to the mosque in the Buyenzi neighborhood of Bujumbura. Hamza had been pressured to join the CNDD-FDD since the 2005 elections.[103] Unlike many other religious leaders who opted to join the CNDD-FDD, he always refused, maintaining that religion was the paramount calling in his life. These political divisions had reportedly created tensions within the Muslim leadership.

Hamza was carrying cash, a watch, and a phone when he was killed. None of these items were taken. Local residents reportedly overheard Hamza talking with the gunman shortly before he was killed; they were apparently arguing about the political content of Hamza's religious sermons.[104]

Two people were arrested in connection with the shooting of Hamza. Two separate sources close to the case told Human Rights Watch confidentially that they did not believe that there was strong evidence linking those arrested to Hamza’s death, and that these arrests may have been intended to distract attention from a more likely political motive. One of them confided that police investigations into the murder had been blocked.[105]

The Killing of Léandre Bukuru

Léandre Bukuru, a businessman and member of the MSD, was taken from his home in the town of Gitega, on the morning of November 13, 2011 by men in police uniforms, driving what was believed to be a police vehicle.[106] The police entered the house without knocking and led him away without explanation. Bukuru’s family and friends made inquiries as to his whereabouts for the next 24 hours, in vain.

The next day his headless body was found in Giheta, a small town 15 kilometers from Gitega. His family tried to reclaim the body from the morgue. Although it had been identified, local authorities informed his relatives that the body had already been buried.[107] They sought redress with the governor of Gitega to obtain custody of the body, but were only allowed to submit a letter requesting the corpse.

Two days later Bukuru’s head was found in a latrine on Nyambeho colline in Gitega province. The following day, after a radio station broadcast information about the killing, provincial prosecuting authorities questioned his family about who had been providing information to the media.[108]

Provincial authorities led the family to believe that they would be allowed to bury the complete corpse according to their wishes. However, the provincial prosecutor later made clear that they would only be given Bukuru’s head and that they would not be allowed to exhume the body. Provincial authorities buried both the head and the body of Bukuru against the family’s wishes.[109]

The CNIDH released a statement deploring the case, raising concern that “similar cases of abductions… often end with execution and hasty burial,” and called on the government to ensure prompt and efficient investigations into such cases.[110]

In January 2012 the prosecutor of Gitega told Human Rights Watch that there was a casefile on Bukuru’s murder, but he was unable to provide up-to-date information on its progress: he said that as senior officers had been cited, the case had been referred to prosecuting authorities at a higher level.[111]

V. Killings of CNDD-FDD Members

While the majority of political killings in 2011 targeted members of the opposition, there have been several instances in which individuals aligned with the ruling CNDD-FDD have been killed or threatened. Information provided by family members and witnesses of these killings broadly points to the FNL, or FNL sympathizers, as the likely culprits in these murders. While judicial officials have tended to open files for these cases more readily than for cases of suspected FNL victims, serious inefficiencies and a lack of capacity in the judicial system mean that many months can pass before the suspected perpetrators are brought to justice, if at all. Suspects who are arrested frequently spend long periods in pretrial detention.