Human Rights Watch has serious concerns that certain provisions of proposed Bill C-31, Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act, are harmful to refugees and asylum seekers and incompatible with international refugee and human rights law. Although the detention provisions of Bill C-31 are ostensibly proposed to deter human smugglers, Human Rights Watch believes that these provisions in fact, target refugee claimants fleeing persecution, who will suffer their consequences.

Human Rights Watch is an independent nongovernmental organization that monitors human rights worldwide. Our most recent World Report, our 22nd annual report, covered human rights conditions in more than 90 countries and territories worldwide in 2011. Human Rights Watch’s Refugee Program defends the rights of refugees, particularly against refoulement, the forcible return of refugees, and advocates for the right to seek asylum and for humane treatment for all forcibly displaced persons worldwide.

Without taking a position on other provisions in Bill C-31, Human Rights Watch would like to raise the following specific concerns with this legislation:

1. Year-long mandatory detention without review

Bill C-31 would provide the Minister the authority to designate certain groups of people arriving in Canada irregularly for a year of mandatory detention without review. The government would have discretion to detain children among the designated groups.

Using detention to penalize refugees for irregular entry into a country contravenes Canada’s obligations under Article 31 (2) of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (the “Convention”). Article 31 prohibits imposing penalties on refugees on account of their illegal entry or presence.

The extraordinary detention provisions proposed by Bill C-31 are explicitly linked to the migrant’s “irregular arrival” without regard to whether the person may, in fact, be a refugee. As such, the rationale for mandatory detention as well as other provisions, such as precluding applying for permanent residence, appears to be punitive and inconsistent with the obligation not to punish refugees on account of their illegal entry.

Refugees fleeing for their lives often do not have the luxury to use “legal” channels to escape. Canada should not forget that in 1939, 907 Jewish refugees arrived on Canada’s shores without proper documentation. Canada denied their entry, and the men, women and children had no choice but to return to Europe. Many died in concentration camps.

Detention of refugee claimants should always be a measure of last resort and should be for reasons clearly recognized in international law, such as concerns about danger to the public, or an inability to confirm an individual’s identity. Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act already provides a system for detention of foreign nationals on these grounds. Current law allows the government to detain any foreign nationals who have not established their identity, are a flight risk, or might be a danger to the public. An independent decision maker reviews whether detention is reasonable within the first 48 hours. Officials must review detention decisions after a week and then monthly until release or deportation. C-31 would remove this scrutiny while a designated person languishes in detention.

The “exceptions” to mandatory detention are unlikely to result in practical relief. The Bill does provide that refugee claimants may be released before a year if a final determination is made on their claim. It is probable, however, that the final determination would not take place within one year given current timelines for refugee processing in Canada, and the fact that a determination would not be considered “final” until all appeals had been exhausted.

Bill C-31’s provisions for one-year’s detention without review similarly contravene the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which provides in Article 9 (4) that:

Anyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings before a court, in order that that court may decide without delay on the lawfulness of his detention and order his release if the detention is not lawful.

Human Rights Watch’s research on immigration detention practices in other countries has shown that the practice can be harmful and inconsistent with human rights obligations unless detainees are afforded the right to promptly challenge the legality of their detention. Our December 2010 report on the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers in Ukraine, for example, documented that the lack of access of judges or other authorities to challenge the legality of detention resulted in arbitrary detention, which contributed to Ukraine’s failure to process asylum claims, corruption, and other problems (see: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2010/12/16/buffeted-borderland-0).

2. Five-year bar on adjustment to permanent resident status

Bill C-31 would preclude designated individuals from applying for permanent resident status for five years after arrival, even if the individual had been recognized as a refugee. This provision, we believe, is incompatible with Article 34 of the Refugee Convention, which provides that:

The Contracting States shall as far as possible facilitate the assimilation and naturalization of refugees. They shall in particular make every effort to expedite naturalization proceedings and to reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings.

Far from the Convention’s entreaty to “make every effort to expedite naturalization,” C-31 would preclude a refugee from applying for permanent residence for five years.

This provision would also have a negative impact on the right of separated refugee families to reunite. The right to family unity is considered by UNHCR to be a fundamental aspect of effective protection of refugee children (see:http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3bd3f0fa4.html). Children, especially unaccompanied children, are some of the most vulnerable migrants imaginable. The delay in family reunification in Bill C-31 could damage both the welfare of the children and their families, as well as the integration prospects for the migrants concerned.

Before obtaining permanent resident status, which would likely take six to seven years after arrival, the individual would have no ability to sponsor and be reunited with family members. Six to eight-year separations could lead to irreparable damage to minor or dependent, unmarried children and to families.

Refugee families become separated for a variety of reasons. For example, some families may become separated in the course of conflict and escape; others may not be able to flee war and persecution at the same time or be able to send all family members overseas at once to seek safety. If one parent of a young family used the family savings to seek safety in Canada and was designated, his or her small children would become grown in the six to seven years that would elapse before their family members could be sponsored to arrive in Canada, during which time those very children would presumably be exposed to many of the same risks that caused the parent to seek refuge in the first place.

The delay in family reunification violates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states in Article 10 that:

….. applications by a child or his or her parents to enter or leave a State Party for the purpose of family reunification shall be dealt with by States Parties in a positive, humane and expeditious manner. States Parties shall further ensure that the submission of such a request shall entail no adverse consequences for the applicants and for the members of their family.

3. Age of majority; Detention of children

Throughout the detention provisions of C-31, the bill refers to designated people as those who are “16 years or older on the day of arrival.” Children under age 16 in the group would either be detained with their parents or separated from them and sent to a child welfare agency. Under international law, 16 and 17 year olds are also children, yet Canada would run afoul of its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child which provides in Article 37 that:

|

(b) No child shall be deprived of his or her liberty unlawfully or arbitrarily. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time; … (d) Every child deprived of his or her liberty shall have the right to prompt access to legal and other appropriate assistance, as well as the right to challenge the legality of the deprivation of his or her liberty before a court or other competent, independent and impartial authority, and to a prompt decision on any such action.

|

The international law standards on detention of children are well-grounded in the findings of child psychology, which show that the impact of long-term detention can be particularly devastating on children. A study published in the journal of the Canadian Pediatric Society documents effects of immigration detention on the mental health of children, which include post-traumatic stress disorder, major depression, suicidal ideation, behavioural difficulties, developmental delay weight loss, difficulty with breast-feeding in infants, food refusal and regressive behaviours, and loss of previously obtained developmental milestones.[1]

4. Power vested in the Minister to designate countries of origin as safe

Bill C-31 would give the minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism exclusive authority to designate certain countries as “safe.” Human Rights Watch has serious reservations about the concept of a “safe-country of origin,” and we would be extremely cautious about putting the decision-making power for adding countries to the list of Designated Countries of Origin (DCO) into the hands of a single, non-independent authority. Refugee claimants from the DCO list would have expedited hearings, would not have access to the new Refugee Appeal Division, and, their applications for leave before the Federal Court would not suspend their removal, so that by the time the court might reverse a denial of asylum, the refugee would already have been subjected to persecution back home.

In introducing Bill C-31 the minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism specifically cited refugee claimants from the European Union as people who should presumptively be regarded as coming from safe countries. Human Rights Watch has documented racist and xenophobic violence directed particularly against Roma and migrants -- and inadequate police protection -- in a number of EU member states, including Italy, Greece, and Hungary. Vigilante groups in Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia and recently in Bulgaria have attacked and held demonstrations against Roma, with inadequate government condemnation of such actions. Although it speaks less to their roles as countries of origin, a number of EU countries also fall short in their treatment of third-country nationals. We have documented inhuman and degrading conditions of migrant detention in Greece and the lack of access to the asylum procedure in Greece and on summary pushbacks of migrants from Greece to Turkey. We have also reported on the treatment of asylum seekers and other migrants in Hungary and Slovakia, including those who have been pushed back to Ukraine from the Hungarian border without adequate consideration of their protection needs.

While we believe that it is impossible to make a blanket determination that any country is safe for everyone and would never produce a refugee, those countries, such as Canada, that have safe-country-of-origin provisions in their law should exercise the utmost caution in making such designations. We do not think that resting the power to make such a decision in the person of the minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism provides adequate consultation for such a consequential decision.

5. Australia’s Experience with Mandatory Detention of Irregular Boat Arrivals

Human Rights Watch has reported on Australia’s unfortunate experience with mandatory detention of irregularly arriving boat migrants, and its failure to account for the needs of vulnerable groups for whom detention can be particularly harmful (see https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/2011_Australia_JointletterUPR.pdf). To the extent that proponents of Bill C-31 see Australia’s experience as a model for this legislation, we urge them to take a closer look at the downsides of the Australia’s use of mandatory detention:

First, based on the Australian experience, Bill C-31 is unlikely to operate as a deterrent to people smuggling. Since the early 1990s, Australia has had a policy of mandatory detention of asylum seekers who arrive ‘informally’ in Australia. As of February 29, 2012, there were 4,944 persons being held in immigration detention in Australia.[2]Prolonged detention has not worked as an effective deterrent to stopping these boats. The Secretary to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Andrew Metcalfe, recently admitted as much, when he said, “Detaining people for years has not deterred anyone from coming.”[3]

Secondly, detention has proved costly in Australia. Andrew Metcalfe, Australia’s most senior and experienced administrator of government immigration policy, confirmed that placing asylum seekers in the community on bridging visas is much less costly, both financially and in human terms, and that the risks of asylum seekers in the community absconding are low.”[4]

Thirdly, prolonged detention of asylum seekers has had serious effects on the physical and mental health and welfare of detainees. Levels of self-harm in Australian immigration detention are extremely high and there were five suicides in Australian immigration detention in 2010/2011.[5] The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has expressed concern that the detention of asylum seekers for prolonged periods of time contributes to psychological and physical health problems for the detainees.[6] The Australian Human Rights Commission has repeatedly found that mandatory and prolonged detention causes distress to people who are often already in vulnerable states, reflected in the high rates of self-harm in detention. The Commission expressed concern that the impact of detention could require significant levels of mental health treatment long after detainees have been released.[7]The Commission’s report on its detention visits make clear the harmful impact of prolonged detention:

During recent visits, the Commission heard from people in detention about the psychological harm that prolonged detention was causing them. People at Villawood spoke of experiencing high levels of sleeplessness, feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness, thoughts of self-harm or suicide, and feeling too depressed, anxious or distracted to take part in recreational or educational activities. The Commission was troubled by the palpable sense of frustration and incomprehension expressed by many people. This appeared to have contributed to marked levels of anxiety, despair and depression, leading to high use of sedative, hypnotic, antidepressant and antipsychotic medications and serious self-harm incidents.[8]

Conclusion

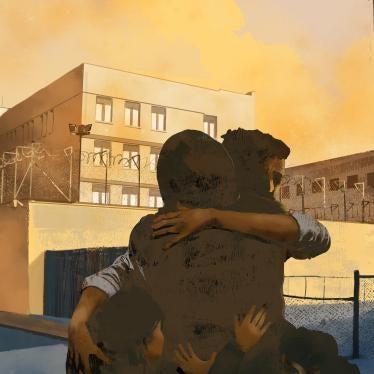

HRW believes that the detention provisions of Bill C-31 unduly and inappropriately impose penalties on vulnerable migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. Instead of identifying and punishing human smugglers, these provisions of the bill would punish irregular migrants, including refugee men, women and children fleeing indiscriminate violence and/or persecution. These people should not be punished on the sole basis of their “irregular” entry.

Canada is not facing an influx of irregular arrivers who pose a real threat or meaningfully strain its resources. Despite the troubled state of the world, there has not been a surge of asylum seekers entering Canada. In fact, Canada had a 30 per cent decrease in asylum claims in 2010 from 2009 and 10 per cent fewer claims in 2009 than in 2008. While there was a 4 per cent increase in the first half of 2011, this was at a time when there was a 17 per cent increase in asylum claims among all industrial states, including a 34 per cent increase in the United States.

In fact 80 per cent of the world’s refugees are in the developing world, straining resources of governments that can barely afford to provide for their own people. Canada received 23,200 asylum seekers in 2010; but an average of 10,000 new Somali refugees arrived irregularly in Kenya every month last year, including nearly 30,000 in August alone. Does a country with Canada’s resources and geographic isolation from war and civil strife really need to punish the relatively few refugees who arrive irregularly?

If the government wishes to target human smugglers, it should allocate greater resources toward investigation and enforcement of the smuggling offences. But detaining the victims is not the answer.

Human Rights Watch strongly urges Members of Parliament to consider the concerns detailed in this submission when studying Bill C-31 and not to enact any provisions that would harm refugees and other vulnerable migrants.

Sincerely,

Human Rights Watch

[1]see Mandatory detention of refugee children: A public health issue?” by Rachel Kronick MD, Cécile Rousseau MD, Janet Cleveland PhD, Paediatrics and Child Health, October 2011, Volume 16 Issue 8, accessible at: http://www.pulsus.com/journals/toc.jsp?HCtype=Consumer&sCurrPg=journal&j...

[2]http://www.immi.gov.au/managing-australias-borders/detention/_pdf/immigration-detention-statistics-20120131.pdf

[4]Testimony of Secretary Andrew Metcalfe to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Subcommittee of the Australian Senate, 17 October 2011, available at: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Festimate%2Fc41d33f3-455d-4f98-ba56-42dc68511fc3%2F0002;orderBy=priority,doc_date-rev;page=19;query=Dataset%3Aestimate;rec=6;resCount=Default

[5]AHRC submission at paras 89 and 92: http://www.hreoc.gov.au/legal/submissions/2011/201108_immigration.html#s7

[6]Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, ‘Health Care For Refugees And Asylum Seekers’, 17 July 2002, available at: http://www.racgp.org.au/refugeehealth

[7]AHRC submission, para 86: http://www.hreoc.gov.au/legal/submissions/2011/201108_immigration.html#s7)

[8]AHRC submission at 86: http://www.hreoc.gov.au/legal/submissions/2011/201108_immigration.html#s7