The South African health minister, Aaron Motsoaledi, took the stage recently in Vienna to address the nearly 20,000 attendees at the 2010 International AIDS Conference. His presence was a testament to the progress South Africa has recently made in controlling the HIV epidemic after years of deadly denial, and his speech was received with hearty, generous applause.

Just four years ago, at the same conference in Toronto, Stephen Lewis, then United Nations special envoy for AIDS in Africa, criticized the South African government for representing a "lunatic fringe" in the global fight against AIDS.

The conference's theme this year was "Rights Here, Right Now," highlighting the importance of human rights in the fight against HIV. And Dr. Motsoaledi acknowledged not simply the progress South Africa has made, but the fact that his country still has far to go in honoring its commitments to protect dignity, life, and access to health services.

But one thing he didn't mention was the right to be free from discrimination. Over the past 30 years, discrimination has driven the AIDS epidemic - making marginalized groups more vulnerable to infection and making those living with HIV unable to access care. South Africa has a heroic history of overcoming apartheid, but xenophobic violence and discrimination continues to be a scourge on the country, undermining the health of migrant populations and impeding AIDS efforts.

In South Africa, migrants - internal and international - are an important group to reach in the fight against HIV, with high rates of HIV and difficult, and often interrupted, access to treatment. Yet, since the emergence of the epidemic in the 1980s, migrant populations have been mostly ignored in the response to AIDS. Mobile populations have less social support and fewer social networks. Isolated from their families, they may seek new sexual partners, with less access to continued prevention or treatment than non-mobile populations. That reality makes HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for migrants a major public health concern.

But South Africa has progressive laws and policies toward migrants' rights, including guaranteeing free antiretroviral therapy for HIV treatment. And South Africa's laws entitle asylum seekers, refugees, and regional migrants to health care, whether they are documented or not. However, these guarantees are not applied uniformly.

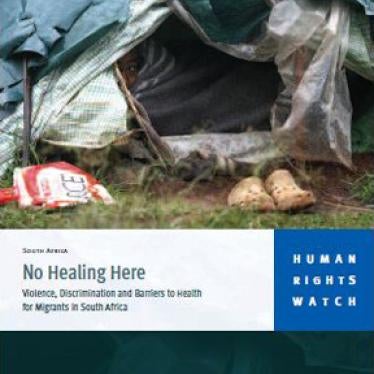

This past December, Human Rights Watch documented serious abuses against migrants in South Africa seeking health care, including HIV/AIDS services. We found that migrants are subject to xenophobic violence, internal displacement, and discrimination. We found that migrants face serious discrimination in health care facilities, including verbal abuse, unlawful user fees, and denial of even basic and emergency health care.

These problems are not unique to South Africa. Human Rights Watch has also documented barriers to HIV treatment for migrants in the United States and Thailand, as well as the vulnerability internal migrants face in getting health care in China, Russia, and India. Japan's policy of excluding undocumented migrants from the public health insurance system is not only bad public health, it can violate fundamental rights to access essential health care services, including antiretroviral therapy.

In 2006, at the United Nations General Assembly, governments around the world committed to a goal of universal access to comprehensive HIV treatment programs by 2010. But 2010 is here, and universal access remains a distant goal, particularly for migrants.

Last year, the Global Fund - to which Japan is a major donor - approved a grant to the Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional political and economic community consisting of 15 southern African countries to improve cross-border HIV responses and target mobile populations. This is an important step toward recognizing that we must fight AIDS at a regional, as well as national, level. In South Africa, leadership is needed to end xenophobic discrimination and ensure migrants' rights to HIV services are protected. While the AIDS conference celebrated "rights here, right now," migrants still too often are told "not here, not now."

Joseph Amon is Director of Health and Human Rights Program of Human Rights Watch. Kanae Doi is Japan Director of Human Rights Watch.