Chile should limit the scope of its military justice system and reform the country's anti-terrorism law so that it can no longer be used to prosecute actions that do not constitute grave crimes of political violence, Human Rights Watch said today.

The legislative branch is currently debating two proposals, one to modify the anti-terrorism law and the other to limit military jurisdiction, presented by President Sebastian Piñera to Congress earlier in September 2010. On September 21, the Chamber of Deputies approved some modifications to the anti-terrorism legislation, which are now being debated in the Senate. The proposals come at a time when at least 32 incarcerated members of the indigenous Mapuche population in Southern Chile are on a hunger strike to protest the application of the anti-terrorism law to their cases, as well as their prosecution by military courts. They began their hunger strike on July 12.

"The debate on long overdue changes to the anti-terrorism legislation and the military justice system is a step in the right direction," said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. "But Chile's lawmakers should make sure that this opportunity to meet its human rights obligations doesn't go to waste."

Anti-terrorism Legislation

Successive Chilean governments have used the anti-terrorism law for years to prosecute Mapuche members accused of common crimes, such as arson and destruction of machinery and equipment. Another problematic practice has been the use of military jurisdiction to try civilians who assault Carabineros, or uniformed police, as well as to try Carabineros accused of human rights abuses against civilians.

The anti-terrorism law is one of Chile's harshest laws. It includes harsher penalties for some offenses, makes pretrial release more difficult, enables the prosecution to withhold evidence from the defense for up to six months, and allows convictions on testimony by anonymous witnesses. Some provisions violate essential fair trial guarantees in international treaties, such as the right of defendants to cross-examine witnesses under the same conditions as the prosecution.

Several United Nations bodies, including the Human Rights Committee, the Committee Against Torture, and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, have expressed concern about using the anti-terrorism law to prosecute Mapuche members for common crimes.

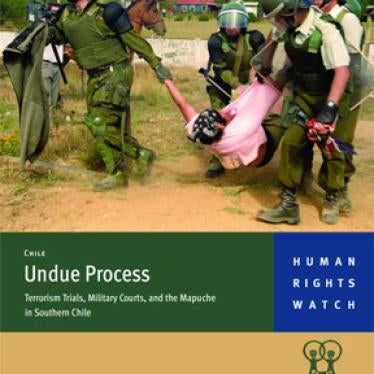

In a report issued in 2004, "Undue Process: Terrorism Trials, Military Courts and the Mapuche in Southern Chile," Human Rights Watch recommended that the anti-terrorism law be modified to ensure that only the gravest crimes of violence involving attacks on life, liberty, or physical integrity are considered terrorist crimes, and then only when the other conditions specified in the law are met. Specifically, Human Rights Watch recommended that the reforms should:

- Prevent unwarranted use of the anti-terrorism law by reforming the Code of Criminal Procedure, which allows any person to lodge an accusation of terrorism. Given the special severity of the anti-terrorism law, the government and the attorney general's office should have exclusive powers to open prosecutions for terrorism.

- Allow the names of prosecution witnesses to be kept confidential only in exceptional circumstances. To ensure respect for due process and the right to defense, the political and judicial authorities should always make the names available in confidence to the defendants and their counsel, except in the most extreme circumstances, when a clear and specific danger to the witness has been proven. The prosecution, however, must first exhaust other means of protecting the witness that do not undermine defendants' rights. In addition, all decisions concerning the protection of prosecution witnesses that affect the conduct of the trial must be subject to appeal. And in instances where the court orders confidentiality, the accused, the prosecutor, and state parties should be strictly prohibited from violating the order by releasing confidential information to the press or public.

- Ensure that criminal acts are never confused with legitimate protest activities or the expression of views on a conflict, however controversial. The government should abide by the 2003 recommendation of the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, who recommended that "[t]he necessary measures should be taken to avoid criminalizing legitimate protest activities or social demands."

Military Jurisdiction

Several Mapuche members are currently being prosecuted in military courts for allegedly injuring law enforcement officials in altercations during protests. Complaints of excessive force or physical abuse by Carabineros against civilians are routinely investigated by military prosecutors and prosecuted under largely secret, written procedures before military courts. These courts do not guarantee the abuse victims a fair and impartial investigation. Most complaints are rejected or left unresolved, and those responsible for the abuses are ultimately not held accountable.

International human rights bodies have consistently rejected the use of military prosecutors and courts in these types of cases, stating that the jurisdiction of military courts should be limited to members of the military and to offenses that are strictly military in nature. Specifically, in the 2005 Palamara-Iribarne case, involving a government effort to prohibit publication of a book about military intelligence matters, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ordered Chile to ensure that military courts no longer exercise jurisdiction over civilians. Despite several attempts by successive administrations for comprehensive reform of the military justice system, Chile has yet to comply with the ruling.

In 2004, Human Rights Watch also recommended that Chile limit the wide jurisdiction of military courts to ensure due process and fair trials for those accused of offenses against the police, and to provide access to impartial justice for victims of abusive conduct by police or military officials. We recommended that:

- All offenses that allow the trial of civilians as defendants be removed from the Code of Military Justice. Civilians should be judged solely and exclusively by ordinary criminal courts under the provisions of the Criminal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure.

- Human rights abuses by Carabineros, such as homicides, excessive or unjustified use of force, illegal arrest, and torture or ill-treatment of detainees, be investigated by ordinary prosecutors and judged in ordinary courts.

- Investigations of alleged human rights abuses by military courts that are still in progress be transferred to ordinary courts.