"We fled home in 2004 and we haven't been back," a 33-year-old woman I will call Solange told me. "We lived in Kiwanja: there was no assistance so we lived for two years in a church; then we lived for two years in a camp." After soldiers destroyed the camp, they fled to the outskirts of a UN peacekeepers' base. "Now the locals want us to leave. So where should we go?"

Solange is not alone in being constantly on the run in eastern Congo, a region ravaged by more than 15 years of war. Millions of men, women and children like her have repeatedly fled the rapidly shifting alliances among myriad armies and armed groups who, when not targeting each other, prey on civilians.

All sides - Congolese and foreign armies and an alphabet soup of armed groups - have committed appalling abuses. Their killings, rape, burning, pillaging and forced labour have forced at least 1.2 million people from their homes in 2009 and early 2010 alone, bringing the number of displaced civilians in eastern Congo to almost 2 million.

They are often among the most vulnerable of the region's war-weary civilians. They have been attacked and abused at every stage of their ordeal. Some live in forests close to their abandoned homes; they sneak like thieves into their own fields by night to find food to keep their families alive.

An estimated 80% of the region's displaced seek shelter in the homes of equally poor families - friends, relatives and strangers - who heroically try to look after them. Only a small minority find refuge in unofficial camps or in camps run by the United Nations.

Many are beyond the reach of humanitarian agencies because the danger or logistical constraints are simply too great. Consequently, with little or no access to food, education or healthcare, many of the displaced take huge risks by temporarily returning to their fields in search of food. That puts them back into the clutches of roaming armed men with no qualms about killing, raping and robbing civilians.

Though many displaced people - one million in 2009 - have returned or tried to return home in recent months, millions more in eastern Congo face huge obstacles: continuing danger in villages far from main roads, accusations from all sides of being collaborators with enemy groups simply because they lived in territory controlled by rivals, looting of their harvests, extortion by ill-disciplined soldiers, disputes over land title, land occupation and property destruction.

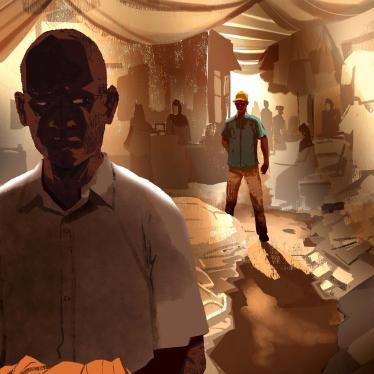

Government officials are anxious to stress that peace has come and that the displaced should go home. To advance their agenda, officials spent months pressuring 60,000 residents of five camps near the town of Goma to go home and then closed the camps overnight in September 2009. Police and bandits raided and looted the camps as they were closing, attacking those who were slow to pack up and leave.

A number of the displaced told Human Rights Watch they didn't even try to go home, because they knew it was still unsafe, while others tried but were forced to leave again by armed groups. Neither the government nor UN agencies monitored what happened to those 60,000 people.

With Congolese army units often abusing the population they are supposed to protect, the government's track record for protecting the displaced is poor. The authorities rely on almost 20,000 UN peacekeepers to do the job. Although the UN has developed some innovative ways to enhance civilian protection, the peacekeepers are overstretched and under-resourced, and the challenge remains immense.

Protecting civilians - including the displaced - should be central to the government's new "stabilisation and reconstruction" policies. First, the government should make sure its "zero-tolerance" policy, prohibiting troops from attacking civilians, is enforced. At the same time, UN peacekeepers should help those still in danger to reach safe locations, secure areas with large numbers of displaced people, and increase the monitoring of areas to which the displaced are returning.

Finally, UN agencies and donors should ensure sufficient resources and priority are given to emergency humanitarian assistance. But such assistance should in no way be used to press the displaced to go home until they are confident it is safe. The crisis in eastern Congo will not be solved until the many thousands of people like Solange can safely return to their homes and their lives without living in constant fear.

Gerry Simpson is senior refugee program researcher at Human Rights Watch