On a sunny morning, we sit in a yurt - a traditional tent used by nomads in Central-Asia - on the central square here in Osh, the epicenter of the violence, as about two dozen women tell us harrowing stories about how their relatives were killed by Uzbek mobs, showing us dozens of photographs of savagely mutilated bodies.

They say the Uzbeks planned and organized the violence to drive the Kyrgyz out so that southern Kyrgyzstan could be united with Uzbekistan. Their fear of new attacks is palpable, as is their desire for revenge.

Later that day, in Osh's Uzbek neighborhoods we hear a completely different story. Ethnic Uzbeks describe how large crowds of enraged ethnic Kyrgyz from surrounding villages looted and burned entire Uzbek neighborhoods and brutally killed those who had not yet fled.

They say that government used military vehicles to remove barricades at the entrances to Uzbek neighborhoods, clearing the way for the Kyrgyz mobs. They accuse the Kyrgyz of genocide, and contend the attacks were organized to clear ethnic Uzbeks- a significant minority in the south-- out of Osh.

We came to Kyrgyzstan with Human Rights Watch researchers to present our report to the Kyrgyz government on these events. More than two months after the violence ended, the Kyrgyz and Uzbek communities, which had frequently inter-married and lived in mixed neighborhoods, continue to live in mutual fear, and many have retreated to the relative safety of their largely mono-ethnic areas.

While some government officials are trying to reconcile the Uzbek and Kyrgyz communities, human rights violations during the investigation into the June events are fueling tensions and distrust.

Just a few hours after we arrived to Osh, an Uzbek family called, insisting that we come immediately. The police had brought 63-year-old "Ruslan" in for questioning the day before. He had returned home barely able to stand, with bruises on his face and neck. As we talked to his relatives, he suddenly cried out in pain, and the family rushed him to the hospital.

With tears streaming down her face, his daughter told us that their shop had been burned down during the violence, that her husband had fled to Russia, fearing arrest, and that they were terrified of the police, who had called again that morning demanding that Ruslan come in for more questioning. It was not difficult to understand her fear and anger at the injustice her family had suffered.

Ruslan's case is not unique. The Human Rights Watch report documented dozens of arbitrary arrests and widespread use of ill-treatment and torture in the aftermath of the June violence, all against ethnic Uzbeks.

We met with several high-ranking government officials, including President Roza Otunbayeva, who were interested in discussing our findings.

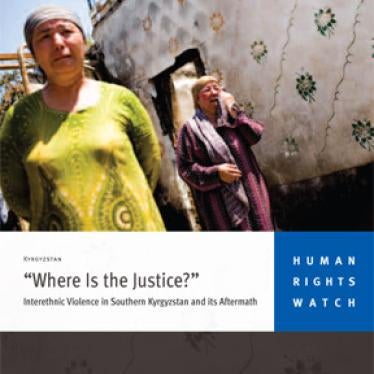

Unfortunately, other officials reacted differently. The prosecutor in charge of investigating the June violence blatantly avoided discussing substantive issues, and instead criticized the report's cover-photo, title, and details in its historical background section. When we brought the conversation back to the well-documented abuses happening right now, he became visibly upset and accused us of being pro-Uzbek. The ombudsman for human rights made similar accusations.

This attitude bodes poorly for the painful but essential process of reconciling the two communities. The government established a national commission to investigate the events, which could help bridge the gap, but before the commission even presented its report, its director already accused an Uzbek leader of masterminding the violence,.

In order for these two communities to reconcile and live together in the future, it is essential that the Uzbek minority regain trust in the authorities, who are almost all ethnic Kyrgyz. Unfortunately, the local authorities have demonstrated that they are not able or willing to protect the Uzbek minority nor to conduct an impartial investigation into the events in accordance with Kyrgyz and international law. International support is desperately needed.

Some support is in the works. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) has agreed to send a small police force to monitor the situation and provide advice. It is absolutely crucial, however, to assign the international police officers to local police stations and allow them to accompany the local police on patrols. Some local officials in Kyrygyzstan have said the officers should be stationed in Bishkek (600 km, 10 hours drive away), but that would be useless. The police force is to arrive in mid-September, more than three months after the violence erupted.

Preparations for an international investigation into the June events are also under way, coordinated by a member of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly. For the investigation to be effective and credible, it will need investigators with substantial relevant expertise and should incorporate a reliable program to protect victims and witnesses. Kyrgyz authorities should cooperate fully, ensuring access to all sites, documentation and witnesses.

The challenges to both an international police force and international investigation are considerable and growing as the country moves toward October 10 parliamentary elections. But we hope that the various institutions and actors involved will remain firmly committed to both and make every effort to start as soon as possible. Tensions in Osh are still high and the sooner the international community sends the international police and opens an international investigation, the less likely that violence will again tear people's lives apart in Osh.

------

Gilles and Marie Concordel, members of Human Rights Watch's Geneva Committee, travelled to Kyrgyzstan following the June violence and its aftermath.