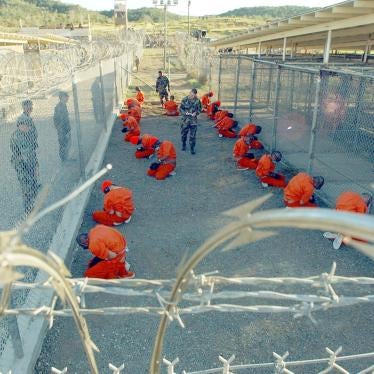

August and September will be big months for the U.S. prosecutors at Guantanamo Bay. Three cases will be moving forward, the first to trial on Aug. 10, a second to pretrial hearings in early September, and a third likely to hearings sometime this fall. Three doesn't sound like many cases, but in context, the number is huge. In the eight previous years that the commissions have been open, they have prosecuted just four terrorism suspects -- none of them high-level al Qaeda operatives. Prosecutors are framing these coming months as proof that the military-tribunal model is working. Common sense, however, says it's not: Federal courts have tried 100 times as many accused terrorists during the same time frame, with far better results.

The summer's first "victory" for prosecutors came early this month, when a one-time cook and driver for Osama bin Laden pleaded guilty before a military commission. The defendant, a slight, 50-year-old Sudanese man named Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi, was charged with conspiracy to commit terrorism and providing material support to a terrorist organization. Before he even left the courtroom, escorted by two military guards, the chief prosecutor approached his team with a congratulatory pat on the back. "The conviction validates the commission process and advances the hearings," the prosecutor, Navy Capt. John F. Murphy, said at a news conference immediately afterward.

Coming after months of bickering and uncertainty about whether and where to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other alleged 9/11 planners in U.S. federal courts, and controversy swirling over a decision to try an ill-treated child soldier by military commission in August, this was just the kind of clean win prosecutors sorely needed to make their case for the beleaguered military commissions.

Unfortunately, one guilty plea hardly validates their argument. If anything, the fact that "victories" like the Qosi trial are so few and far between is proof that the military commissions aren't working. The disparity between how many cases Guantanamo Bay has taken to trial and the record of U.S. federal courts -- already at a stark four vs. 400, respectively -- might soon become even worse. Two of those four are being appealed. The defendants argue they were convicted on charges other than war crimes and so shouldn't have been tried by the commissions. The appeals could drag on for years.

When it comes to the three Guantanamo cases likely to make headlines in the coming months -- Omar Khadr, Noor Uthman Muhammed, and Mohammed Kamin -- the military commissions' trials are likely to prove similarly muddy and prolonged. There is no question that the cases on the docket would pose a challenge to even a well-established system of justice. But in a system created from scratch, in a remote locale that requires all participants to be flown in and out for short visits, problems that would be minor irritants in a U.S. court become major obstacles. The result can be months or years of delay.

Even beyond the human rights questions about due process guarantees and the military commissions' unfair rules, the Guantanamo tribunals have not shown themselves up to the task of prosecuting even low-level terrorism suspects. Does it really make sense to leave the prosecution of the alleged 9/11 planners -- the men accused of the worst terrorist act on U.S. soil ever -- in the hands of an untested system with an abysmal track record? Anyone who has seen the military commissions in action would say no -- and a review of the upcoming cases suggest why this is true.

- Omar Khadr

The most controversial prisoner is Canadian citizen Omar Khadr, who was just 15 when he allegedly committed his crime -- throwing the grenade that killed U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Speer and wounded two others in 2002. His case became big news when the video of his interrogation in 2003, showing what appears to be torture, was leaked. Now 23, Khadr's trial is set to begin on Aug. 10 (unless Canada intervenes, which a Canadian federal judge has ordered it to do).

Pretrial hearings have gotten off to a rocky start. On July 12, Khadr, now 23, told the commission that he turned down a plea bargain that would have resulted in just five more years in prison because he would not plead guilty to a crime he didn't commit. He fired his lawyers on July 7 and said he intends to "boycott" the proceedings. The judge then ordered Khadr's military counsel to represent him anyway.

Courtroom drama aside, Khadr's alleged grenade-throwing is hard to justify as a war crime. A grenade is a lawful weapon and a soldier is a lawful target, even if Khadr's actions violated local criminal law. The military commissions have gotten around this by considering any act by an "unprivileged belligerent" to be a war crime.

Even trickier is the fact that Khadr was a juvenile when he was taken into U.S. custody. Although it is not technically illegal to prosecute a minor for war crimes, doing so is unprecedented in U.S. -- and indeed in modern world -- history. Moreover, international and U.S. law require certain procedural protections when prosecuting child offenders, none of which have been followed at Guantanamo. The government's own witnesses say that Khadr was interrogated while strapped down on a stretcher just 12 hours after sustaining life-threatening injuries and was threatened with rape if he did not cooperate.

If that were not enough, there are also real questions about the facts in the case. During pretrial hearings, considerable doubt was cast over whether Khadr actually threw the grenade that killed Speer. The prosecution had claimed that Khadr was the only insurgent alive at the time that the grenade was thrown. But a document inadvertently released to the media in February 2008 revealed that a U.S. operative killed another insurgent before shooting Khadr twice in the back. For his part, Khadr initially told interrogators that he threw the grenade, but the defendant now denies that, saying that his confession was coerced.

- Noor Uthman Muhammed

The next case to come to pretrial hearings -- this September -- will likely be that of Noor Uthman Muhammed, a Sudanese national accused of working at and recruiting for an al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan during the late 1990s. Among other allegations, the United States claims he delivered a fax machine to Osama bin Laden. Noor's lawyers argue that he was ill-treated in U.S. custody and hence statements made to interrogators should not be admitted into evidence.

From the beginning, Noor's case has been a slow, awkward dance between the defense, the prosecution, and the judge, each of whom has access to a different set of classified documents regarding the case. The prosecution claims that the volumes of information it intends to use are too secret for the defense to see. This is not terribly uncommon in federal courts, and clear procedures are put forth in the Classified Information Procedures Act. But ironically, the military commission judges and prosecutors have no experience with this process. So there have been countless delays in processing the scrubbed summaries that pass from the U.S. government to Noor's counsel, after being approved by the judge.

Noor's case has also been marred by counsel issues. In October 2008, one of the prosecutors in Noor's case, Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld, resigned, saying that he did not think detainees could receive fair trials at the military commissions. The government subsequently withdrew the charges and then refiled them in December 2008.

Meanwhile, Noor's own assigned military counsel, Army Maj. Amy Fitzgibbons, with whom he had established a good working relationship, temporarily left active duty in November 2009. She continued to represent Noor and hoped to continue doing so after starting a new job with the Army's Trial Defense Service in March. However, the Army said she was "unavailable" to serve as his counsel given her new responsibilities representing troops in courts-martial. In taking the new position, she cut the attorney-client relationship, the Army explained. A final solution has yet to be worked out, but Noor boycotted his subsequent hearing on June 30. This issue, of course, would never have arisen in federal court.

- Mohammed Kamin

Unlike the other detainees charged before the military commissions, Mohammed Kamin, an Afghan in his 30s, is charged with only one offense: providing material support for terrorism. The government alleges that he performed "at least one of the following": attending an al Qaeda training camp; offering the use of his residence to al Qaeda; delivering weapons, supplies, or equipment to al Qaeda; conducting surveillance of U.S. forces; or placing land mines and missiles in specified locations.

Regardless of which act or acts Kamin did allegedly commit, material support is not a war crime, as even the Defense Department's own counsel, Jeh Johnson, admitted while testifying to the Senate on July 7, 2009. Countless legal experts have disputed the inclusion of this offense as one triable by military commission, despite its inclusion in the Military Commissions Act of 2009 signed into law by President Barack Obama. Any convictions could hence be overturned on appeal.

Kamin joins Khadr and Noor in boycotting the proceedings at Guantanamo. The one time he appeared, for his arraignment in May 2008, he was forcibly extracted from his cell. Since that time, when told of hearings in his case, he has reportedly placed earplugs in his ears, pulled a blanket over his head, and waved away the officials.