With about 3,000 Kenyan women and girls developing obstetric fistula each year, you might think the government would have a plan to prevent and treat it. Think again.

Obstetric fistula is a childbirth injury which results in constant leaking of urine and faeces. Interviews I conducted with 53 women and girls living with fistula, as well as officials, health professionals, donors and others, revealed major shortcomings in the health system's response to preventing and treating fistula, as well as reintegrating women in their communities if they are among the few lucky enough to get surgical repair.

A woman who develops fistula has already gone through the trauma of a long, painful, obstructed labour. In many cases, the labour ends in a stillbirth. As the woman begins to recover from the grief and agony of the failed delivery, she discovers that her body is painfully damaged. She loses control of urine or stool, or both.

She might think that she is suffering from temporary, somewhat abnormal incontinence. But then she begins to smell, her clothing and bedding are constantly wet, her thighs sting, and she might develop ulcers on her reproductive organ.

She might not afford creams to ease the pain, or sanitary pads, and instead will use rugs to control the constant trickle of urine and faeces. At first, the woman might try to hide her condition, but that is usually impossible. Sex is painful, and her marriage might start to fray, or even turn violent.

She might be thrown out by her husband. Her relatives and friends may think she is bewitched and refuse the food she touches or bar her from their homes. In all likelihood, she will stop working, going to the market, and taking part in social or religious life.

She might live in pain and isolation for years, even decades, before learning that surgery could repair her condition. This news will not be enough if she lacks the resources to pursue surgery. Exactly how many fistula sufferers there are in Kenya, and globally, is impossible to say with certainty because of poor data collection. Some experts say there may be far more cases than the current estimate by the government and the UN of about 3,000 new cases per year and 300,000 existing cases.

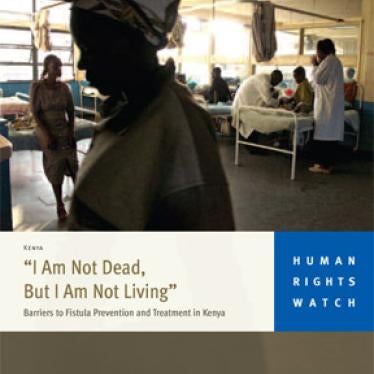

It is also not clear how many cases are repaired each year, but experts estimate about 1,000, largely through free repair camps sponsored by international agencies and non-governmental organisations. Most of the women and girls with fistula whom I met during surgical repair camps in Kisumu, Kisii, Machakos and Nairobi, as well as in Dadaab town, were primary school dropouts from rural areas.

They had poor knowledge of family planning and contraception; they married early, some as early as 14, and became pregnant young. Decisions on where they would deliver were often made by their husbands or mothers-in-law. Kenya has some very good policies on reproductive and maternal health. However, it has no national strategy for addressing fistula.

If Kenya's plans to reduce preventable maternal deaths and childbirth injuries such as obstetric fistula are to work, the government needs to ensure that public health facilities are properly staffed and equipped and access to them is equitable throughout the country.