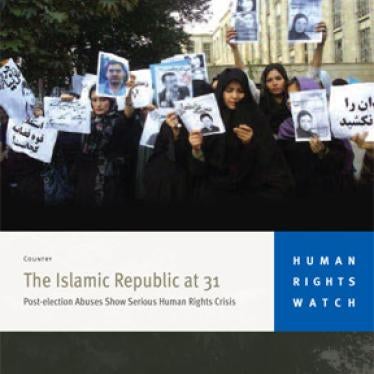

One year after the disputed Iranian presidential election, the atmosphere in Iran is markedly different than the images of mass protests beamed across the airwaves and through cyberspace a year ago. Public demonstrations of dissent have all but disappeared and protesters have been forced underground -- Iran is more of a closed society than ever.

The Iranian government repeatedly harasses civil society activists. Hundreds of protesters arrested during or in the months following the demonstrations languish in jail. Of those,, 250 have been tried and convicted, according to the Iranian judiciary. But many of those still in jail have never been charged, tried or convicted, and many of them have been denied access to lawyers or family members for weeks or months on end.

At least six have been sentenced to death for their participation in the "green revolution." And at least nine other dissidents have been hanged in the past year.

The government has specifically targeted journalists, bloggers and human rights defenders for arrest, presumably because of their effectiveness in gathering information and communicating it to people both inside and outside of Iran.

The government, at first overwhelmed by ordinary Iranians spreading information about the protests through cell phones, e-mail, and social media sites, has stepped up its censorship. It increasingly relies on sophisticated surveillance, filtering, and jamming technology to disrupt the flow of information to and from Iran's mobile-phone, Internet, and satellite users.

Over the past six months, an increasing number of civil society activists and journalists have reported that their phone calls are being tracked, their Internet connections slowed down, and their email accounts monitored.

Both during and after last year's demonstrations, Iranian security forces arrested thousands of protesters and killed scores more in one of the Islamic Republic's most brutal episodes of state-sponsored violence since its founding in 1979.

The political dissidents executed in the last year were charged with the vague crime of moharebeh, or "enmity against God." Six of them belonged to Iran's Kurdish minority. More than a dozen Kurdish activists remain on death row and may be executed at any time.

Despite this, Iran nearly won a spot on the UN Human Rights Council, the UN body responsible for addressing abuses such as those perpetrated by the Iranian government. Iranian and international human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, spoke out against Iran's candidacy, and Iran ultimately withdrew from the election.

Yet Iran still received a spot on the UN's Commission on the Status of Women.

Iran's nuclear issue has distracted the international community from the country's abysmal human rights problems. On Wednesday, the UN Security Council voted to impose new sanctions on Iran because of its nuclear program. While the nuclear issue is extremely serious, that is no reason to ignore the extreme human rights abuses endured by Iranian citizens who don't share in their government's views.

On June 10 -- two days before the anniversary of the protests -- Iran rejected a number of important human rights recommendations made by the Human Rights Council in February as part of a periodic review process. The member states had said that Iran should stop executing political prisoners and children, implement policies to end violence against women, and allow the UN special rapporteur on torture to visit the country.

When it comes to addressing the aftermath of the protests, the international community should push for transparent, independent investigations. Outside observers still do not have reliable figures on how many people were killed, tortured, or detained, and no high-level government official has been brought to account for the abuses. Those found, after investigation and trials, to have had a role in the abuses should be brought to justice.