They had been beaten, whipped, shocked with electric batons and even raped. Food was scarce and forced labor common. Cambodians who have spent time in the country's drug detention centers described these outrageous abuses and horrible conditions, and more.

People in these detention centres - including adults, children and individuals with mental illness - were detained without ever seeing a lawyer, a judge or a courtroom. Some had been picked up in "street sweeps", others yanked out of bed at night. Their families had paid the police to come and "arrest" them and put them in, what they hoped were, treatment facilities.

But "treatment" in these facilities consists of military drills, hard labor and forced exercise. Detainees are forced to work and exercise to the point of collapse, even when they are sick and malnourished. These centres offer no medically appropriate treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy, psycho-social support (counseling, for example) or opiate substitution therapy. As one former detainee explained, his centeR was "not a rehab center but a torture center."

In September 2009, Human Rights Watch wrote a six-page letter to the chairman of the National Authority for Combating Drugs, asking for background and statistical information about the centers, the legal and policy framework under which they operate, and the government's approach to drug treatment. In January 2010, we requested official meetings to discuss the findings of our nearly year-long investigation.

We got no response.

The government has responded to the press though.

The government has sometimes declined comment, sometimes evaded direct response, or attacked the organization instead of addressing the facts. But the government also acknowledged certain abuses and revealed a perspective on drug dependence deeply out of touch with scientific evidence.

Khieu Sopheak, a spokesman in the Ministry of the Interior, said the government was looking into the report, but emphasized that Human Rights Watch was often critical of the Cambodian authorities. They are "seeing only one tree - they do not see the jungle," he said.

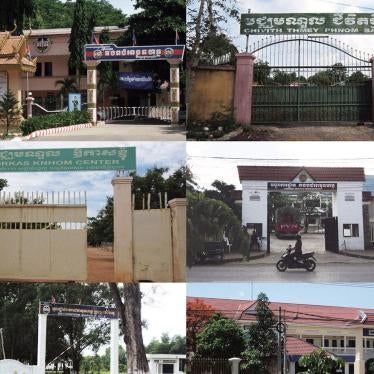

Huot Sokhom, the deputy chief of the police-run rehab center in Siem Reap, denied allegations that people are forced into drug treatment, explaining, "Those vagrant people we collect from the streets volunteer to come with us". Meanwhile, in the neighboring province of Banteay Meanchay, the commander of the military police detention center described to the press how detainees at his center were forced to stand in the sun or "walk like monkeys" as punishment for attempting to escape.

Not one government official contacted by the press suggested that our reports of the lack of counseling, peer support, or opiate substitution therapy - international norms of drug treatment - were untrue. In fact, the Interior Ministry spokesperson, Khieu Sopheak, insisted that those in detention "need to do labor and hard work and sweating - that is one of the main ways to make drug-addicted people become normal people".

Drug dependency can be a chronic condition, with abusers prone to relapses. I'm not sure whether that is a tree or jungle, but sweating is no treatment for drug addiction.

The World Health Organization concurs: Its officials have said that close to 100 percent of those in Cambodian detention centers relapse, and that it does not support the centers. UNAIDS and its country representative say that the centers are clearly illegal and should be shut down.

Abusive conditions in drug detention centers have also raised international concerns. Manfred Nowak, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture, has said that withholding adequate health or medical treatment may constitute or contribute to "inhuman or degrading treatment." The UN high commissioner for human rights, Navi Pillay, has said that drug users are "all too often ... forced to accept treatment, marginalized and often harmed by approaches that over-emphasize criminalization and punishment while under-emphasizing harm reduction and respect for human rights".

With the Cambodian government denying most of the abuses, and the international community increasingly speaking out against them, where do we go from here?

Under international law, the Cambodian government must investigate credible allegations of torture and ill treatment. The government should begin these investigations immediately. Surya Subedi, the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Cambodia, should clearly communicate to the government that these centers violate international human rights law, and press for their permanent closure. United Nations agencies in Cambodia should do likewise.

Voluntary, community-based drug treatment urgently needs to be expanded within Cambodia, but the release of individuals from abusive, ineffective and illegal detention centres should not be delayed. Individuals who use drugs do not forfeit their human rights, and the Cambodian government should not create detention centers that are exempt from the protections afforded to all.