The Greek sunshine has never shone brighter than in the picture interior minister Prokopis Pavlopoulos paints of how Greece "secures the right of each foreign immigrant, at any point of entry, to apply for asylum" and "sets rules for the protection of human trafficking victims and of unaccompanied minors". The shameful reality, however, takes place in the dark of night, not at official points of entry but in Greece's border areas with Turkey, the port of Patras and the Aegean Sea where Greek border officials abuse unaccompanied child migrants and asylum seekers.

Pavlopoulos is right about one thing: Greece is on the European Union frontline, and needs closer co-operation with the EU to protect the union's external borders. But rather than co-operation based on high standards and mutual respect, it appears that other EU member states are all too willing to look the other way as Greece performs their dirty work of keeping migrants out.

"Daoud", a 14-year-old Afghan boy, told me how the Greek coastguard intercepted his inflatable boat in May 2007, beat him and the other migrants, took them within sight of the Turkish coast, removed the engine and oars, punctured the boat and set them adrift. "The police beat all of us," the boy told me. "They told us not to come back."

When they sighted the Turkish shore, Daoud said, "The police put us back on our rubber boat. We had a small engine, but the police took the engine and the two oars. The police made a hole in the boat. When we were at sea before we were caught the boat was okay, but when we were put back in the water it was punctured. We tried to paddle with our hands ... The wind was head on and nobody had life vests."

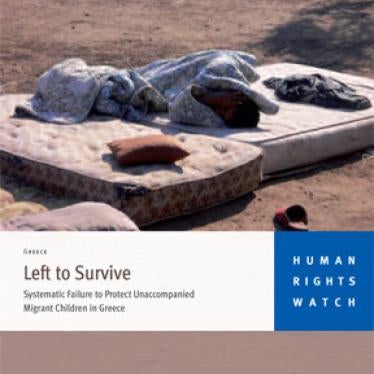

Unaccompanied children on land don't fare much better. Migrants in the border region with Turkey, including children, are held in overcrowded conditions in police stations until a group of 60 to 100 are gathered. At nightfall, armed guards take them to the Evros river, wait until Turkish border patrols are gone and then push them across. Human Rights Watch interviewed 41 migrants in various locations in Greece and Turkey who told a consistent story of summary expulsion.

Children who reach Athens remain at great risk. I found "Fatime", a young unaccompanied Somali girl, in the Petrou Ralli jail there. It was her fourth time in detention. "I am 10 years old," she said. "I told the police how old I am, but they haven't had another place for me ... I am alone. I have nobody here. If they release me, I'll just go to Omonia square. I have no one. I have been in Greece for six months."

The area around Omonia square in downtown Athens is crawling at night with pimps and drug dealers, hardly a safe place for a 10-year-old girl. Fatime had not been seen by any specialised services since she was detained.

Children often go to the port city of Patras, the departure point for Italy. Ghulam, an Afghan boy, was caught hiding in a truck in Patras. He told me: "The police forced me to lie flat on the ground with my arms stretched out. One guy pressed my head down with his boot ... then he called the others to kick me and they all kicked me. They kicked me one after the other for about five minutes ... One pulled out his gun. He held it to my head and said 'I will kill you'. He pulled the trigger but the gun was empty ... Afterward they asked me how old I was. I said I was 14. They all started laughing. Then they told me to leave and run fast. They came running after me and shouted to scare me."

The asylum approval rate in Greece in the first nine months of 2008 was 0.03%, according to the interior ministry. Children are intimidated during their asylum interviews, asked leading questions and given no meaningful opportunity to tell their stories.

"Hamed", an Afghan boy, said: "I told the [interpreter] that I wanted to explain my problems. At that point the police officer shouted at me ... I thought if I said something more the police would kick me out without documents. I was scared. [The interpreter] said two or three times that I should say I came for a better life. The interview took five minutes."

Hamed told me that he had fled Afghanistan because he was threatened by a local commander. "This person wanted to keep underage boys for dancing and more ... The commander threatened me and said if I complained to anybody he would kill me."

Children fleeing horrors at home should not have to face new horrors in Europe. As Pavlopoulos says, Greece is a party to all the relevant human rights conventions, including conventions specifically for children and for refugees. But the ugly reality at the Greek margins of the EU is very different. The union and every one of its members share the responsibility to see that children at its frontier are not mistreated, that those found responsible for committing crimes against them are held accountable and that the Greek government brings its detention and asylum systems up to the standards required of Europe, or any civilised society.

Simone Troller is the Europe researcher for Human Rights Watch's children's rights division