When Gordon Brown met Nigerian President Umaru Yar'Adua in London this week, improving the security of energy supplies from the Niger Delta was high on the agenda.

Sabotage and oil theft have cut production in the world's eighth-largest oil exporter to its lowest level in 20 years, contributing to spiralling world oil prices.

For obvious domestic political reasons Brown wants to be seen to be doing something about those high prices, and he has already indicated that the UK is ready to offer increased assistance to the Nigerian military in order to restore oil production and return law and order in the Niger Delta region. But if Brown wants to get tough on energy insecurity he needs to get tough on the causes of energy insecurity.

In the Niger Delta the rampant violence is just a symptom of a deeper problem: rampant corruption. Since at least 2003, politicians from the ruling People's Democratic party, determined to maintain their control of oil revenues, have directly fuelled escalating violence in the Niger Delta and elsewhere in Nigeria.

Political kingmakers have used the government funds at their disposal to sponsor criminal gangs and secure election victories through violence and vote-rigging. Many of the armed criminal gangs operating in the Delta gained their power through the patronage and impunity accorded them by influential ruling party politicians.

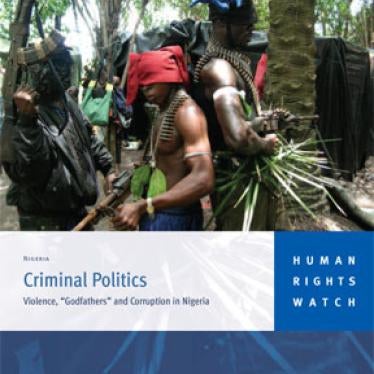

Human Rights Watch has conducted extensive research into this disturbing phenomenon. Its findings were published in a report last October: Criminal Politics: Violence, "Godfathers" and Corruption in Nigeria.

The impact of all this political corruption is not just attacks on oil facilities and higher oil prices. There are important human rights dimensions at play here too. In July and August 2007, gangs in Port Harcourt - the capital of Rivers State - unleashed an unprecedented wave of attacks against the city and its people. Gangs fought each other in the streets with automatic weapons, explosives, machetes, and broken bottles. They opened fire on crowds at random, gunning down scores of terrified civilians in the streets. People who had been walking home from work on ordinary afternoons suddenly lay dying on the operating tables of nearby clinics.

With world oil prices closing in on $150 a barrel, Nigeria's government coffers are filling at record pace. Nowhere is the oil bonanza more evident than in the state governments of the region. In Rivers State, the volatile heart of the oil industry, the state government's $3bn annual budget far exceeds the entire central government budgets of most West African nations.

However, while government coffers collect windfall oil revenues, ordinary Nigerians derive precious little benefit from this tremendous wealth. Abject poverty in Rivers State ranks among the worst in the world. Oil revenues that could have been spent on improving health and education for Nigeria's citizens are instead squandered and embezzled by the political elite. According to British investigators, some of this oil wealth has made its way to the UK. In 2007, a British court froze some $35m in assets belonging to former Delta State governor James Ibori. His official salary while in office was around $25,000.

President Yar'Adua came to power in May 2007 following deeply flawed elections that the head of the EU monitoring team described as one of the worst EU monitors had ever observed. Yar'Adua promised to champion the rule of law and tackle endemic corruption. But these pledges have rung hollow in the face of continued impunity enjoyed by the political elite.

Hope for anything but business as usual was dashed in December 2007 when the dynamic head of Nigeria's Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) was forced to resign. Two weeks earlier, the EFCC had taken the bold step of arresting Ibori, widely believed to have been one of the key financiers in Yar'Adua's election campaign, and had indicated its willingness to follow suit with Rivers State former governor Peter Odili, who is accused of presiding over the theft and mismanagement of several billion dollars during his eight years in office.

Here's what Brown should do this week at his talks with President Yar'Adua if he wants to help Nigeria address the spiralling violence in the Delta and ensure better governance country-wide.

He should push the Nigerian leader to ensure that Nigeria's police and anti-corruption officials conduct criminal investigations into government officials credibly linked to sponsorship of armed gangs, including powerful former governors. He should urge Nigeria to launch a transparent and impartial public inquiry into links between politics, corruption, and violence in Rivers State. He should press Yar'Adua to re-empower the EFCC, follow through quickly on these two indictments and then start on the rest. And closer to home Brown should announce a dedicated UK police team to investigate money laundering in the UK by the Nigerian political elite.

Unless there is a determined effort to address the root problem of political and financial corruption, the violence in the Niger Delta will continue to have a disastrous impact on energy security - and on the lives of ordinary Nigerians.

Eric Guttschuss is Human Rights Watch's Nigeria researcher.