Many Zimbabweans fleeing to South Africa since 2005 – possibly numbering tens of thousands – have escaped persecution. They are refugees, although South Africa’s dysfunctional asylum system has yet to recognize them as such.

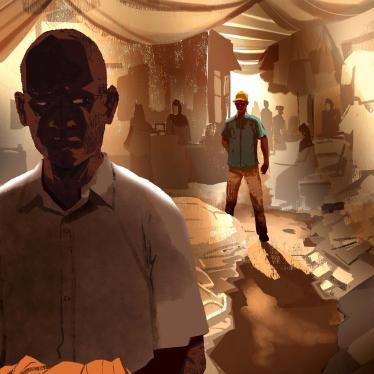

Three years ago, Mugabe’s government ordered Grace’s cottage in Harare to be bulldozed, together with the homes of 700,000 other people, and banned all informal street and market trading. Grace, her daughter and her mother lost everything: home, work, income, education and healthcare.

Grace has barely survived. “After they destroyed my cottage we slept in the open. I tried to feed us by trading in the street but the police always stole my goods and then arrested, fined and beat me with a rubber whip and then with an iron bar,” she told me in February. “It was impossible to get a trading license because I did not have a ZANU-PF card. After they beat me with the iron bar I knew could not continue and had to leave to survive. So I came to South Africa.”

Grace and 700,000 others were victims of “Operation Murambatsvina” or “Operation Clear the Filth,” a name that reflects the ruling ZANU-PF party’s low regard for the humanity of these Zimbabwean citizens. Carried out shortly after the March 2005 elections in which the opposition party made significant gains in Zimbabwe’s cities, ZANU-PF viewed Grace and others living in high-density suburbs as a political threat that had to be removed. Like those abused by Mugabe’s thugs in 2008, Grace, and hundreds of thousands like her, were all targeted for the same political reason: they apparently threatened ZANU-PF’s hold on power.

Many Zimbabweans fleeing to South Africa since 2005 – possibly numbering tens of thousands – have escaped the same persecution, and the same destructive economic effects, described by Grace. They are refugees, although South Africa’s dysfunctional asylum system has yet to recognize them as such.

They join an estimated 1.5 million Zimbabweans who have fled the appalling conditions caused by Mugabe’s destructive economic policies. Zimbabwe has the world’s highest rate of inflation (100,000 per cent); 83 per cent of its people live in poverty, 80 per cent are unemployed, and 4.1 million depend on food assistance, which government operatives withhold or manipulate for political gain. Life expectancy for women, 56 years in 1978, has fallen to 34 today; over 70 per cent of the 350,000 Zimbabweans in need of life-saving HIV/AIDS drugs cannot access them.

These Zimbabweans – refugees and people fleeing generalised economic ruin – have turned to their South African neighbors in search of safety and work to help send home food and money. But almost all enter and remain in South Africa without documents, have no right to work and only limited access to help such as health care. Even if registered as asylum seekers – which should guarantee them protection from forcible return to Zimbabwe – they are liable to be arrested and summarily deported. Exploited by employers and at risk of xenophobic violence, they live in permanent insecurity. Destitute and vulnerable when they arrive, they remain so in South Africa.

Zimbabweans’ presence underlines a failure of foreign policy: the failure to use South Africa’s leverage to effectively address the brutal human rights violations and failed economic policies causing their flight. Their undocumented status and vulnerability in South Africa also represents a failure of domestic policy: the failure to develop a comprehensive policy to address the reality of their presence.

To begin the long-term process of securing a future for Zimbabweans in Zimbabwe, South African must end its failed and discredited “quiet diplomacy” approach towards Mugabe. But trying to address the cause of forced displacement in Zimbabwe is not a substitute for attending to the needs of Zimbabweans in South Africa. Pretoria needs to tackle both failures now.

South Africa should provide temporary residence status and work authorization for all Zimbabweans in South Africa. By doing this, South Africa would stop violating international refugee law by deporting asylum seekers, help protect Zimbabweans against exploitation and violence inside South Africa, facilitate their self sufficiency, and enable them to help their desperate families at home.

Granting temporary status to Zimbabweans would also unburden South Africa’s asylum system, currently clogged with thousands of Zimbabwean claims, and ensure that Zimbabweans earn the minimum wage, which would help South Africans to compete fairly with them for jobs. By doing the right thing to help its desperate neighbors, South Africa could also lessen the resentment behind the recent rise in xenophobic violence that has caused so much damage – not least to South Africa’s reputation.