(Abidjan) - Pro-government and rebel forces in Côte d'Ivoire have subjected thousands of women and girls to rape and other brutal sexual assaults with impunity, Human Rights Watch said in a new report issued today. Despite recent progress in the peace process, the latest accord fails to address this widespread sexual violence or the need for accountability.

While the worst sexual violence took place during the height of the armed conflict from 2002 to 2004, women and girls continue to be subjected to acts of sexual violence.

"Sexual violence has been the silent crime of Côte d'Ivoire's military and political crisis," said Peter Takirambudde, Africa director of Human Rights Watch. "Combatants responsible for rape and other acts of sexual violence have enjoyed almost complete impunity, while the survivors have been denied both justice and medical attention."

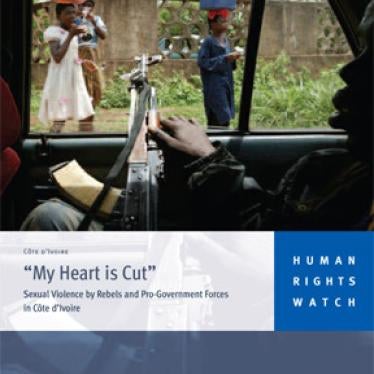

The 135-page report, "My Heart is Cut: Sexual Violence by Rebels and Pro-Government Forces in Côte d'Ivoire," details the widespread nature of sexual violence throughout the five-year military-political crisis. The report, which is based on interviews with more than 180 victims and witnesses, documents how women and girls have been subjected to individual and gang rape, sexual slavery, forced incest and other egregious sexual assaults.

Fighters on both sides have raped women old enough to be their grandmothers, girls as young as 6, pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers. They have also inserted guns, sticks, pens, and other objects into their victims' vaginas. Combatants have abducted women and girls to serve as sex slaves, and have forcibly conscripted them into the fighting forces. Sexual violence has been often accompanied by other gross human rights violations against the victims, their families and their communities, including torture, killing, mutilation and even cannibalism.

Côte d'Ivoire - once considered a pillar of stability and progress in West Africa - has for at least seven years been consumed by a political and military crisis rooted in ethnic, religious, political and economic issues. Efforts to resolve the armed conflict between the government and northern-based rebels have produced a string of unfulfilled peace agreements, the deployment of more than 11,000 foreign peacekeeping troops, and the imposition of a UN arms embargo and travel and economic sanctions. In March, the government and rebels signed the Ouagadougou Agreement, envisioned to bring about an end to the crisis and lead to elections later this year. To date, both sides have taken encouraging steps toward its implementation, but the peace process has not resolved key issues that have contributed to the breakdown of previous accords in the past, particularly the criteria for establishing Ivorian citizenship, disarmament, and accountability for abuses by all sides.

Victims of sexual violence told Human Rights Watch about the acute physical and psychological distress they suffered as a result of rape. The report details how some rape victims died because of the sexual violence they endured. Others were raped so violently that they suffered serious bleeding, tearing in the genital area, long-term incontinence, and severe infections. Others suffered from botched abortions following the sexual assault. Many complained of bleeding, deep abdominal aches, and burning pains. Countless victims suffered from sexually transmitted infections and were put at high risk for the transmission of HIV/AIDS. Deterred by shame and poverty, few survivors of sexual violence ever receive the medical help they need.

The Ivorian government and the rebel New Forces (Forces Nouvelles) have made scant efforts to investigate or prosecute perpetrators of even the most heinous crimes involving sexual violence. This failure has contributed to an environment of increasingly entrenched lawlessness where impunity prevails. For its part, the international community has consistently sidelined initiatives to combat impunity in Côte d'Ivoire, presumably due to a fear of upsetting negotiation efforts.

"The government and the rebels alike have turned a blind eye to rape and other abuses committed by their forces," said Takirambudde. "This has only emboldened perpetrators on both sides of the military divide."

Sexual violence took place throughout Côte d'Ivoire, especially in the hotly contested western regions, which experienced the most fighting. Mixed groups of Liberian and Sierra Leonean fighters - operating as mercenaries in support of both the Ivorian government and rebel forces - were guilty of especially egregious and widespread sexual abuse. However, even after the end of active hostilities, from 2004 onwards, sexual violence has remained a significant problem throughout both rebel- and government-held areas.

In rebel-held territory, and particularly in the west, some women were targeted for abuse because of their ethnicity or perceived pro-government affiliation, often because their husband, father or another male relative worked for the state. Many others appeared to have been targeted randomly for sexual assault. Women and girls were subjected to sexual violence in their homes, as they sought refuge after being found hiding in forests, when stopped at military checkpoints, while working on farms, and at places of worship. Numerous women and girls were abducted and subjected to sexual slavery in rebel camps where they endured sexual abuse over extended periods of time. Resistance was frequently met with horrific punishment or even death. Some sex slaves, intimidated by their captors and the other circumstances, felt powerless to escape their life of sexual slavery. An unknown number of such women and girls remain with their captors.

Pro-government forces - including members of the gendarmerie, police, army, and militias - were widely responsible for rape and other forms of sexual abuse against women and girls, especially in the heavily contested western region and along frontlines. In addition to sexual violence associated with open hostilities, pro-government forces targeted women and girls whom they suspected of supporting the rebels, particularly women who were Muslim, came from the north or from neighboring Burkina Faso and Mali, or were thought to support opposition political parties. Law enforcement officers, militia men, and other pro-government forces abused women at checkpoints, during raids, in makeshift prisons, and in marketplaces. The scale of violations by pro-government forces appeared to increase during periods of heightened political tension.

Human Rights Watch called on the Ivorian government and rebels to investigate and punish perpetrators in accordance with international standards. The United Nations Security Council should expedite the publication of the report of the 2004 UN Commission of Inquiry into human rights violations committed since 2002, and should discuss its findings and recommendations. The Ivorian government and its development partners must act promptly to provide much-needed medical, psychological and social services to the countless survivors of sexual assault. Lastly, given the fact that rights abuses have very often escalated during periods of heightened political tension, Human Rights Watch emphasized that drawdown or withdrawal of United Nations peacekeepers must wait until after presidential and legislative elections.

"Ivorian and rebel authorities must demonstrate their commitment to the rule of law now and in the future by committing to prosecute key individuals responsible for atrocities, including those atrocities documented in this report," said Takirambudde. "The organizations and governments working to consolidate peace, namely the United Nations, the French government and the African Union, must assist them in developing a concrete strategy for doing this."

Selected testimony from victims interviewed for the report:

One young woman who was in her late teens when she was detained in 2003 as a sex slave in a rebel camp recounted:

"They took me and for a week they raped me all the time, they locked me in a home. They used to tie me up with my legs spread apart and arms tied behind me to rape me. They'd rape me three or four in the night, they would put their guns next to you and if you refuse they kill you. They killed one of my friends and made us bury her. We were about 10 or 15 girls there, being raped."

A mother who was raped and whose two adolescent daughters had firewood shoved into their vaginas by rebels in 2002 described her agony:

"Frankly I don't know how I will cope. They took sticks to put in the vaginas of my two daughters ... When they took out the wood they put their hands in. Really, they ruined my children. The blood was running ... they told me to wipe it up. Wood, hands ... when they were done ... they beat my girls again and said they will kill us. I had to clean up the blood from my daughters."

A woman of Malian origin, living in a predominantly Muslim neighborhood of Abidjan, described how she was raped by soldiers in front of her husband on March 25, 2004:

"During the crisis which followed the opposition march, I was raped by the military. They came into our house. My husband was in the living room and my three children were in their rooms. The soldiers locked the kids up. I was just coming out from the shower. They forced my husband to sit and watch them raping me under the threat of their guns. This shame prevents me from looking at my husband today."

A Muslim woman of Malian origin described the gang-rape of her sister by seven uniformed pro-government soldiers who wanted to ascertain the whereabouts of their brother, an opposition activist:

"My big brother was in the RDR ... They came looking for him. We [my sisters and I] said "he is out." They said, "we will kill the three of you if you don't get him to come." They found a notebook with his number and called him. He said "I am coming, just take some money, please don't hurt them." They hit me with a gun and broke my arm. Then they took my beautiful tallest older sister, tied her up and raped her over and over."

A woman who had been raped for over a year during the war by rebels in Bouake explained her appalling physical condition after managing to escape:

"I could hardly walk, was bleeding all the time. I had no money for cloths to stop the bleeding or even for food ... I was so sick, they chased me away from the hospital, my living conditions were awful, I smelled bad, I couldn't sleep, I crawled like a baby because I couldn't walk, I felt so bad, I didn't have anyone to help me."