(Lagos) - Despite Nigeria’s progress on democratic reforms, Nigerian police routinely commit brutal acts of torture that have endured since the country’s era of military rule, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

Across Nigeria, both senior and lower-level police officers routinely commit or order the torture and mistreatment of criminal suspects. Human Rights Watch urged foreign governments funding police reform in Nigeria to be more critical about police abuses, such as torture.

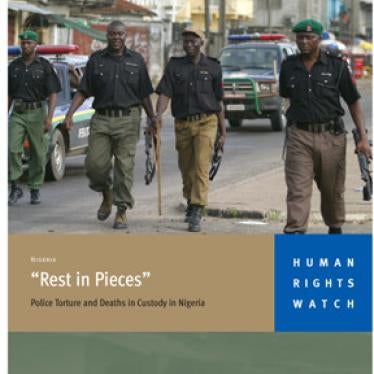

The 76-page report, “‘Rest in Pieces’: Police Torture and Deaths in Custody in Nigeria,” is based on over 50 interviews with victims and witnesses of torture and is the first comprehensive study on the subject. The report documents brutal acts of torture and ill-treatment in police custody, dozens of which resulted in death.

“For too long, the police in Nigeria have gotten away with murder and brutality,” said Peter Takirambudde, executive director of the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch. “If President Olusegun Obasanjo wants to show the world that he is serious about pursuing justice, he should ensure that police torturers are held accountable for their crimes.”

Most victims were arrested within the context of an aggressive government campaign against common crime and were tortured to obtain confessions. They were tortured in local and state police stations across Nigeria, often in interrogation rooms especially equipped for the purpose.

Forms of torture documented by Human Rights Watch include the tying of arms and legs behind the body, suspension by hands and legs from the ceiling, severe beatings with metal or wooden objects, spraying of tear gas in the eyes, shooting in the foot or leg, raping female detainees, and using pliers or electric shocks on the penis.

In addition, witnesses reported that dozens of suspects died as a result of their injuries; others were summarily executed in police custody.

“They handcuffed me and tied me with my hands behind my knees, a wooden rod behind my knees, and hung me from hooks on the wall, like goal posts,” said a 23-year-old man who was arrested in Enugu in June 2004.

“Then they started beating me. They got a broomstick hair [bristle] and inserted it into my penis until there was blood coming out,” he said. “Then they put tear gas powder in a cloth and tied it round my eyes. They said they were going to shoot me unless I admitted I was the robber. This went on for four hours.”

The majority of the torture victims interviewed were ordinary criminal suspects whose cases were characterized by an absence of due process of law. Typically, suspects were not informed by the police of the reasons for arrest, received no legal representation, and were subjected to excessive periods of pretrial detention. Once the suspects were brought before a court, judges and magistrates often accepted confessions extracted under torture.

“The Inspector slapped me with a belt and then a wooden stick. She beat all over my body and also my face. I can't count the number of times she did this. Two other male officers were present and watching,” said a 31-year-old woman arrested in Lagos in January.

“Next the policemen tied a rope around my arms and body and hung me up from a hook in the ceiling,” she said. “Again, the Inspector beat me with a belt and wooden sticks and sprayed tear gas in my private parts. She said I will never have peace in my life as I am a liar. She wanted me to agree to the crime, that I duped my boss and stole the money.”

Police torture in Nigeria is often socially accepted because it has been common for so long. A culture of impunity has protected the perpetrators. When victims and others have tried to attain accountability they have faced harassment, intimidation and obstruction by the police.

The absence of independent mechanisms to investigate police abuses and make referrals to the prosecutor has created a serious accountability vacuum. This has allowed the perpetrators to evade justice. In recent years, not a single police officer has been successfully prosecuted for committing torture in Nigeria.

“The United States and Britain have invested millions in police reform initiatives in Nigeria, but police practices have changed little since the end of military rule,” said Takirambudde. “Diplomatic relations have taken precedence over concern for human rights for too long. It’s time the British and the U.S. governments conditioned further aid to the police to measurable improvements in police conduct.”