As the G8 leaders meet in Gleneagles, Scotland, all eyes are on Prime Minister Tony Blair as he canvasses support for increased aid and debt relief. The prime minister has called this a ‘real moment of opportunity’ to promote democracy and growth throughout Africa.

In Nigeria, one of Britain’s key allies on the continent, the Secretary of State for International Development, Hilary Benn said in May, ‘What happens in Nigeria is crucial for the future of Africa as a whole.’ He went on to announce backing for President Olusegun Obasanjo’s quest for debt relief. Nigeria owes almost $36 billion to the Paris Club of creditor nations and Britain’s support will be crucial in persuading others to agree to end payments. Benn cites the strides Obasanjo has made in tackling corruption, improving transparency and accountability, and implementing ‘impressive and much needed economic reforms.’ He pledged to triple the aid programme from $64 million in 2003 to $182 million in 2007.

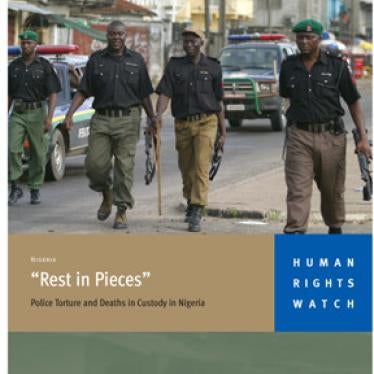

In some respects, the progress is real. And yet, the British government makes no mention of serious human rights abuses that persist in Nigeria, six years after the end of military rule. Thousands have died in communal conflict, the 2003 elections were characterised by fraud, ballot-rigging and violence, and law enforcement agents, most notably the Nigerian police, regularly torture and kill.

Britain is spending $55 million on a five year, Security, Justice and Growth Programme, a major component of which is collaboration with the police. A flagship community policing programme in the southeastern state of Enugu is scheduled to expand to five other states later this year. Through intensive skills development and leadership training of local officers, it aims to bring major attitudinal change and improvements to police community relations.

It sounds impressive. However, on a recent visit to Enugu State there was little evidence of improvement in police behaviour. Earlier this year, I interviewed fifty victims of alleged police torture from eight states, including Enugu. The forms of brutality they described were shocking and reminiscent of abuse in the military era.

A twenty-three-year old man told me how police in Enugu tied his hands and legs and suspended him from a ceiling fan hook. For four hours he was beaten, had broom bristles inserted into his penis and tear gas powder rubbed in his eyes.

Other victims have described beatings with cable wire, iron bars, wooden planks, pressure from concrete blocks on the arms and back while suspended, the rape of female detainees, the use of pliers or electric shocks on the penis, shooting in the foot or leg, stoning, death threats, and the denial of food and water.

Many have died as a result of their injuries. Others are summarily executed. In the northern city of Kano, four men, held for periods of up to 23 months, told me they witnessed the death of at least twenty people during their detention. A police officer acknowledged to me, ‘There are many cases at the police headquarters where the police intentionally shoot people. They are shooting roughly one person per week.’

The majority of the victims I spoke to were ordinary criminal suspects, arrested for alleged crimes, ranging from petty theft to armed robbery. Many were detained either because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, or on the basis of unverified tip-offs. Again and again, the police failed to inform suspects of the reasons for their arrest, or produce evidence against them.

The primary function of torture was to extract a confession. Victims described how they were forced to write or sign a statement, often without knowing what it said because they could not read, or because officers withheld the document from them.

Torture is perpetrated by and with the knowledge of senior officers, some of whom are known by the nickname OC (Officer in Charge) Torture. It is carried out in local and state police stations, often in interrogation rooms which appear to be especially equipped for the purpose.

In February last year, a 22 year old student from Enugu was arrested by officers who told him he looked like an armed robber who had just stolen a motorbike. Despite protesting his innocence, he was taken to the Enugu State police command and brutally beaten with a metal rod while suspended by his hands from the ceiling. When he refused to admit to stealing the motorbike – no evidence was produced, nor was a complainant named – he was taken to a senior officer. Holding a gun to his head, the officer said that unless he admitted the crime he would be shot. He then ordered his juniors to beat him then and there. The student was forced to sign a statement admitting the crime.

I met the man in prison where he was awaiting trial on charges of armed robbery, a capital offence in Nigeria. He said, ‘When I think about what happens it pains me so much. Why did this happen? How did I end up here? Now I just don’t know what to do.’

The use of torture has become an acceptable method of interrogation and perpetrators are protected by a culture of impunity. Decades of military rule has entrenched violent and brutal policing practices. Many victims do not even think to question their treatment. When asked if they would complain to the police the typical response was, ‘I don’t have power so I can’t do anything to challenge the police,’ or ‘who am I to complain, I have no power.’

Those who do try to complain face intimidation or harassment. Two school girls from Enugu told me how they were gang-raped by three police officers in September 2004. They were aged 17 and 18 at the time. With the support of a local human rights organisation, they complained to police authorities. Shortly afterwards they received repeated phone calls from the Enugu State police spokesman and the principal accused who said, ‘If you don’t drop the case, I will deal with you and show you I am a man.’

In the rare instances that cases are brought before a court, obstruction from the police and connivance with members of the judiciary ensure the perpetrators are seldom held accountable. As far as Human Rights Watch has been able to establish, no police officer alleged to have committed torture has been successfully prosecuted.

Senior officers deny the undeniable. The head of the police in Kano State boasts that he has never received a complaint of torture or ill-treatment. He told me: ‘I’ve never found that torture has been used to extract confessions. It never happens here.’

Since 1999 national efforts to reform the police have failed to introduce accountability or bring about a reduction in abuse. In January, Sunday Ehindero, the new head of the force, announced an ambitious programme of reform, promising to improve intelligence and investigative capacity, expand community policing, and change the philosophy and attitudes.

Theoretically, the reform programme could bear fruit. But success will depend on political backing from Obasanjo. There is little sign of that. Since coming to power in 1999, the president has shown little interest in justice. No one has yet been charged or tried for the massacre of hundreds of people by the Nigerian military in Odi, Bayelsa State, in 1999 and in Benue State, in 2001. Nigeria continues to provide a home for former Liberian president Charles Taylor, despite indictments against him for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity by the Special Court for Sierra Leone.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly asked the British government to raise concerns about police abuses with the Nigerian authorities. So far there has been a notable reluctance to do so. Nigeria’s importance as a major oil-producing country and its regional influence in Africa have apparently proved more valuable than the need to protect the fundamental rights and freedom of Nigerians.

British assistance in community policing can help bring change, but it must be accompanied by an end to the silence on human rights issues, especially police abuses. There has been no reduction in police torture or killings since the end of military rule.

As London prepares to increase development assistance to Nigeria, it is high time that, at the very least, continued funding of police reform should be made conditional on improvement in conduct. If what happens in Nigeria is crucial for the whole of Africa, ministers should publicly denounce torture and call for an end to impunity for abuses. They should listen to the two girls who were gang-raped by policemen in the very state where the community policing programme runs, ‘We want the policemen to be punished. We need justice.’