Torture in Egypt is a widespread and persistent phenomenon. Security forces and the police routinely torture or ill-treat detainees, particularly during interrogation. In most cases, officials torture detainees to obtain information and coerce confessions, occasionally leading to death in custody. In some cases, officials use torture detainees to punish, intimidate, or humiliate. Police also detain and torture family members to obtain information or confessions from a relative, or to force a wanted relative to surrender.1

While torture in Egypt has typically been used against political dissidents, in recent years it has become epidemic, affecting large numbers of ordinary citizens who find themselves in police custody as suspects or in connection with criminal investigations. The Egyptian authorities do not investigate the great majority of allegations of torture despite their obligation to do so under Egyptian and international law. In the few cases where officers have been prosecuted for torture or ill-treatment, charges were often inappropriately lenient and penalties inadequate. This lack of effective public accountability and transparency has led to a culture of impunity.

Police and state security agencies continue to use torture in order to suppress political dissent. In the past decade, suspected Islamist militants have borne the brunt of these acts. Recently, increasing numbers of secular and leftist dissidents have also been tortured by police and security officials. In March and April 2003, for instance, the authorities tortured and ill-treated in detention some demonstrators and alleged organizers of public protests against the U.S. led war in Iraq.2

Egyptian police regularly detain street children they consider “vulnerable to delinquency” or “vulnerable to danger.”3 During arrest these children are routinely beaten with fists and batons. Children also told Human Rights Watch that police subjected them to sexual violence or tolerated sexual violence by adult detainees while in custody. They face brutal and humiliating treatment and, in some cases, this ill-treatment was so severe as to constitute torture.4

In addition, groups made vulnerable by stigma or social marginalization continue to be subject to police torture and ill-treatment. Many men arrested solely for consensual homosexual conduct, or suspicion thereof, have been beaten and tortured in police custody.5

Methods of torture include beatings with fists, feet, and leather straps, sticks, and electric cables; suspension in contorted and painful positions accompanied by beatings; the application of electric shocks; and sexual intimidation and violence.

Deaths in custody as a result of torture and ill-treatment have shown a disturbing rise in the past two years. Egyptian human rights organizations report at least ten cases in 2002 and seven in 2003 [see Appendix]. The Prosecutor General’s office opened criminal investigations in some of these cases following formal complaints filed by human rights lawyers and family members. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, none of these investigations have led to criminal prosecution or disciplinary actions against the perpetrators.

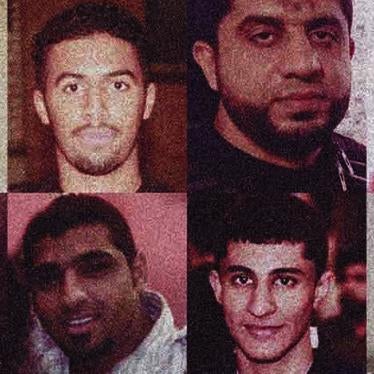

In the September-November 2003 period alone, Egyptian human rights organizations reported four cases of deaths in custody.

- The Cairo-based Human Rights Centre for the Assistance of Prisoners (HRCAP), reported thatMuhammad `Abd al-Sattar al-Roubi, a 26-year old engineer, died on September 19 while in State Security Investigations (SSI) custody in Ebshiway detention center in Tibhar (al-Fayyum), after being tortured in an attempt to extract from him a confession regarding his political affiliations. The HRCAP reported that SSI officers told al-Roubi’s father that his son had committed suicide. No autopsy report was made public stating the cause of death.6

- The Association for Human Rights Legal Aid (AHRLA), an Egyptian human rights organization, reported that Muhammad `Abd al-Qadir, thirty-one, died on September 21, 2003, after being tortured in SSI custody in Cairo. Family members who saw Muhammad while he was still in custody said he told them that he had been beaten and tortured with electricity, and that marks of this torture were visible on his face and body. On September 21, police reportedly told his family that Muhammad had been moved to al-Sahil hospital; hospital officials then told the family his body had been moved to the Zainhum morgue for forensic examination. No forensic report was made public. AHRLA reported that medical personnel at the hospital told the family that Mohammad died as a result of being harshly beaten, and family members who saw the body said it bore evident signs of torture and ill treatment.7

- The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights (EOHR) reported that Mahmud Gabr Muhammad–a worker and resident of the al-Sayyida Zainab neighborhood– died on October 4, 2003, while being detained without charge in the al- Sayyida Zainab police station. Mahmud was arrested that day while he was in a café. A relative of the victim told EOHR that there were visible injuries on the corpse, including bruises under the knee, bleeding from the mouth, and other injuries all over the body. EOHR called for an investigation and a forensic examination in order to determine the cause of death.8

- On November 6, 2003, the EOHR reported the death in custody of Mas`ad Muhammad Qutb, an accountant at the Engineers’ Syndicate. He was reportedly arrested on November 1, 2003, by the SSI for being a member of the banned Muslim Brotherhood. He died on November 4, 2003, while being transferred from the SSI office in Gabir Ibn Hayan to Umm al-Masryyin Hospital. EOHR, citing al-Duqi police station report (No. 9214/2003), said that the Prosecutor General’s investigation confirmed signs of inflicted injuries on the corpse and ordered a forensic examination to determine the cause of death. 9

Egypt is party to the major human rights treaties dealing with torture, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture). Hence, Egypt is strictly obliged to prohibit any form of torture and ill-treatment and to take positive measures in order to protect victims of torture by carrying out thorough, impartial, and prompt investigations into allegations of torture and ill-treatment and filing criminal charges where appropriate. However, Egypt did not sign the Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, which establishes a mechanism for receiving individual complaints. Egypt also entered reservations with regard to Articles 21 and 22 of the Convention against Torture. Those articles affirm the right of State parties to the Convention to file torture-related complaints against another state as well as the right of victims of torture to file grievances directly with the committee that oversees compliance with the Convention.

Article 42 of Egypt’s Constitution provides that any person in detention “shall be treated in a manner concomitant with the preservation of his dignity” and that “no physical or moral (m`anawi) harm is to be inflicted upon him.” Egypt’s Penal Code recognizes torture as a criminal offence, but the definition of the crime of torture falls short of the definition in Article 1 of the Convention against Torture. For example, under article 126 of the Penal Code, torture is limited to physical abuse, occurs only when the victim is “an accused,” and only when torture is being used in order to coerce a confession. While confessions are frequently the object of torture, this narrow definition improperly excludes cases of mental or psychological abuse, and cases where the torture is committed against someone other than “an accused” or for purposes other than securing a confession.

Article 126 of the Egyptian Penal Code only penalizes acts of civil servants or public employees who commit or order acts of torture. The definition of torture in Article 1 of the Convention against Torture, by contrast, also covers situations when “pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity,”

Egypt’s Penal Code also fails to provide for effective punishment of law enforcement officials responsible for torture and ill-treatment. Article 129 of the Penal Code states that any official who subjects persons to “cruelty,” including physical harm or offences to their dignity, “shall be sentenced to an arrest period of no longer than one year, or with a fine not to exceed L.E. 200 [$30].” Article 280 of the Penal Code provides for similarly inadequate penalties regarding illegal detention.

Articles 63 and 232 (2) of Egypt’s Code of Criminal Procedure give the Office of the Prosecutor General exclusive authority to investigate allegations of torture and ill-treatment, even in the absence of a formal complaint, to bring charges against police and SSI officers, and to appeal court verdicts. However, under articles 210(1) and 232(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure persons filing complaints against police for torture or ill-treatment do not have the right to challenge any decision, be it administrative or judicial, by the prosecutor’s office. These articles prevent victims of torture from challenging arbitrary or capricious decisions by the Prosecutor General, thus granting the authorities effective immunity from judicial review, and thus unfettered discretion in determining how to respond to complaints of torture.

In practice, the government undertakes very few investigations and dismisses the seriousness of the problem of torture and ill-treatment in the country. Egyptian authorities admit only to “the occasional case of human rights abuses.”10 One factor underlying Egypt’s failure to investigate and punish acts of torture by law enforcement officers may be the apparent conflict of interest in placing the responsibility to monitor places of detention, order forensic exams, and investigate and prosecute abuses by officials within the same office that is responsible for ordering arrests, obtaining confessions, and successfully prosecuting criminal suspects.

Medical evidence is crucial to determining whether torture has been committed. In the absence of medical evidence or a forensic report the Prosecutor General need not undertake an investigation, much less a criminal prosecution, but access to specialists in the Justice Ministry’s department of forensic medicine requires referral by the Prosecutor General or a court. The Prosecutor General is under no obligation to provide a referral in prompt and timely manner.

The government’s failure to investigate promptly and impartially credible allegations of torture and ill-treatment of political detainees and ordinary citizens, even in many cases of death in custody, has fostered a culture of impunity and contributed to the institutionalization of torture. In the rare instances where the courts have convicted officials of torture, penalties have been lenient. The authorities do not provide information on the number of complaints received, and have seldom divulged criminal, administrative or civil actions taken in relation to incidents of death in custody or torture and ill-treatment.

Under Egyptian law, victims of torture and the dependent heirs of those who have died in custody may file a claim at the administrative court for compensation and for violations of personal freedoms protected by the Constitution. Victims of torture are usually reluctant to bring civil lawsuits for fear of retribution by the perpetrators and a desire to put the experience behind them.11 In addition, when plaintiffs are successful the courts rarely award compensation that is “fair and adequate,” as mandated by Article 14(1) of the Convention against Torture.12 This, coupled with the absence of an effective system of criminal prosecution of torturers, makes torture very “affordable” for the Egyptian government.

The U.N. Committee against Torture, the U.N. Human Rights Committee and the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture have consistently expressed concern at the persistence of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment at the hands of law-enforcement personnel, in particular the security services. These bodies also criticized the lack of investigations into such practices, punishment of those responsible, and reparation for the victims.13

Despite Egypt’s lamentable record on torture and ill-treatment, in recent years several countries, including the United States and Sweden, have extradited or rendered into Egyptian custody persons wanted by the government for alleged security-related offenses.14

Recommendations to the Government of Egypt

I) Policy Initiatives and Administrative Reforms:

- Acknowledge the scale of torture in Egypt and its serious implications for Egyptian society. Initiate broad public and internal debate involving the Ministry of Interior, the Prosecutor General, the People’s Assembly, the presidency, and relevant nongovernmental organizations about causes of and solutions for the problem of torture.

- Issue and publicize widely a directive from the President of the Republic stating clearly that acts of torture and ill-treatment by law-enforcement officials will not be tolerated and that reports of torture and ill-treatment will be promptly and thoroughly investigated and perpetrators will be criminally prosecuted.

- Direct the Office of the Prosecutor General to fulfil its responsibility under Egyptian law to investigate all torture allegations against law enforcement officials, including allegations filed by a third party (for instance, a human rights organization).

- Establish an independent body, under the authority of the judiciary and comprising judicial, legal, and medical experts known for their independence and integrity, to oversee investigations of allegations of torture and ill-treatment by law enforcement officials and to evaluate the performance of the Office of the Prosecutor General with respect to due diligence in this regard.

- Insure the independence of the Office of the Prosecutor General from political interference and activate prosecutorial oversight of all places of detention. Mandate prosecutors to conduct unannounced inspections of all places of detention, speaking to all inmates in conditions of privacy, and taking complaints.

- End the practice of arresting children considered to be “vulnerable to delinquency” or “vulnerable to danger” and ensure that no child is subject to arrest, detention, or imprisonment except as a measure of last resort, and then only for the shortest possible time. In all such cases, children should be held separately from adults unless it is in their best interest to do otherwise.

- Ensure that victims of torture have prompt access to medical care and forensic medical examinations and remove obstacles to the use of independent forensic examinations in criminal proceedings,

- Maintain and make available to the public at least on an annual basis information and statistics regarding allegations and complaints of torture filed, and the legal and administrative responses to those allegations and complaints.

II) Legal Reforms:

- Amend Article 126 of the Penal Code to make the definition of torture consistent with Article 1 of the Convention against Torture.

- Amend provisions prohibiting torture and ill-treatment by officials, in particular Penal Code Article 129 on the use of cruelty by officials, and Article 280 on illegal detention, to make the penalties commensurate with the seriousness of the offenses and reclassify these offences as felonies rather than misdemeanours.

- Amend Articles 210 and 232 of the Penal Code to allow persons filing complaints of police abuse to challenge any prosecutorial decision not to investigate credible allegations of torture or not to prosecute those suspected of committing acts of torture and ill-treatment.

III) Transparency and international obligations:

- Ratify the first Optional Protocol to the ICCPR to allow the Human Rights Committee to receive and consider individual complaints regarding violations of the ICCPR.

- Make the necessary declaration under Article 22 of the Convention against Torture allowing the U.N. Committee against Torture to receive and consider individual complaints submitted by victims of torture and ill-treatment.

- Invite the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture and the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit and report on conditions in Egypt.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (2002) under which state parties agree to allow independent international experts to conduct regular visits to places of detention within the country; to establish national mechanism to conduct visits to places of detention; and to cooperate with the international experts.

Recommendations to the Arab League

- Call upon the Egyptian government to respect and comply fully with the principles and obligations laid down in the Arab Charter on Human Rights (1994), and specifically to meet its obligations under Article 13 of the Charter, which reads:

"(a) The States parties shall protect every person in their territory

from being subjected to physical or mental torture or cruel, inhuman or

degrading treatment. They shall take effective measures to prevent such

acts and shall regard the practice thereof, or participation therein, as

a punishable offence."

Recommendations to the African Union

- Call upon the government of Egypt to respect its commitments under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981), and to take effective steps in accordance with the Guidelines and Measures for the Prohibition and Prevention of Torture, Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in Africa, adopted in 2002 by the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, to end the practice of torture in Egypt.

- Request that Egypt invite a committee of experts from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to investigate and report on the problem of torture and ill-treatment of detainees.

Recommendations to the International Community

- Raise with the government of Egypt in all official meetings concerns over widespread torture and ill-treatment of detainees in police stations and security interrogation facilities.

- Insist that Egypt take concrete and effective legal and policy steps to end the practice of torture and ill-treatment to hold accountable those responsible, and to provide fair and adequate redress for victims of torture.

- Assist the Egyptian government with training programs for police, prosecutors, judges, and forensic doctors, with special emphasis on combating torture and treating the victims of torture and ill-treatment.

- · Decline to extradite or render to the Egyptian authorities any person until the government has taken concrete and effective steps to stop the practice of torture and hold criminally responsible those law enforcement officials who order, condone, or commit such acts. Do not accept diplomatic assurances as sufficient for purposes of extradition or rendition.

Egypt: Reported Deaths in Custody owing to Torture and Ill-Treatment, 2003

|

Name & Age |

Date of Detention |

Date of Death in Custody |

Place of Detention |

Actions Taken |

Source |

|

`Abdullah Rizq `Abd al-Latif |

|

May 2003 |

October 6th police station |

|

EOHR communication |

|

Ahmad Muhammad `Umar |

June 1, 2003 |

July 6, 2003 |

al-Mahalla al-Kubra police station |

|

AHRLA communication |

|

Ragab Muhammad `Afifi Zidan |

July 16, 2003 |

July 16, 2003 |

al-Minia police station |

Family filed case with Public Prosecution office. Forensic doctor confirmed that body did not show signs of suicide, contrary to claims made by the authorities. |

EOHR communication |

|

Muhammad `Abd al-Sattar al-Rubi, 26 |

September 12, 2003 |

September 12, 2003 |

Ebshiwai detention center, Tibhar, al-Fayyum |

Family filed case with Public Prosecution office. Forensic Doctor assigned to the case. |

HRCAP communication |

|

Muhammad `Abd al-Qadir, 31 |

September 14, 2003 |

September 21, 2003 |

Hadayyiq al-Qubba police station |

|

AHRLA communication |

|

Mahmud Gabr Muhammad |

|

October 4, 2003 |

al-Sayyida Zainab police station |

|

EOHR communication |

|

Mus`ad Muhammad Qutb, 43 |

November 1, 2003 |

November 6, 2003 |

al-Duqi police station |

|

EOHR communication |

Egypt: Reported Deaths in Custody owing to Torture and Ill-Treatment, 2002

|

Name & Age |

Date of Detention |

Date of Death in Custody |

Place of Detention |

Actions Taken |

Source |

|

Sayyid Khalifa `Issa, 24 |

January 26, 2002 |

Unknown |

Nasr City police station |

2 officers sentenced to 3 years in prison on August 8, 2002; 2 others acquitted; 4 officers received one year suspended sentences and 1000 L.E fines |

EOHR annual report |

|

Ahmad Taha Yusif, 42 |

February 23, 2002 |

February 23, 2002 |

al-Wayli police station |

Case referred to Cairo Criminal Court July 11, 2002 |

EOHR annual report |

|

Midhat Fahmy `Ali, 35 |

March 10, 2002 |

March 10, 2002 |

al-Gumruk police station |

Pending charges against one police officer for cruelty |

EOHR annual report |

|

Muhammad Mahmud `Uthman, 25 |

May 27, 2002 |

May 28, 2002 |

Masr al-Qadima police station |

Complaints filed by family & EOHR |

EOHR annual report |

|

Mustafa Labib Abu Zaid, 25 |

Was already in prison |

July 3, 2002 |

Shubra police station |

Complaints filed by family & EOHR |

EOHR annual report |

|

Muhammad Muhammad Shahin, 44 |

June 18, 2002 |

July 8, 2002 |

Wadi al-Natrun 430 prison |

|

EOHR annual report |

|

Nabih Muhammad `Ali Shahin, 33 |

June 18, 2002 |

July 8, 2002 |

Wadi al-Natrun 430 prison |

|

EOHR annual report |

|

Ibrahim `Umar Mustafa, 29 |

August 8, 2002 |

August 10, 2002 |

Giza police station |

Complaints filed by family & EOHR |

EOHR annual report |

|

Shibl Bayumi Ibrahim, 32 |

September 11, 2002 |

Unknown |

Tanta Security Directorate |

Family & EOHR complaints |

EOHR annual report |

|

Ahmad Khalil Ibrahim, 35 |

October 1, 2002 |

October 4, 2002 |

al-Gumruk police station |

Family & EOHR complaints |

EOHR annual report |

1 See, for example: Human Rights Watch World Report 2003,(New York, 2003), p. 434; World Report 2002 (New York, 2002), pp. 415-16; World Report 2001 (New York, 2000), pp. 373-74; World Report 2000 (New York, 1999), p. 346; World Report 1999 (New York, 1998), pp. 347-48.

2 Human Rights Watch, Security Forces Abuse of Anti-War Demonstrators, Vol. 15, No.10(E), November 2003.

3 These categories, set forth in Egypt’s Child Law 12 of 1996, have become a pretext for mass arrest campaigns to clear the streets of children, obtain information about possible criminal activity, and force children to move on to other neighborhoods.

4 Charged with being Children: Egyptian Police Abuse Children in Need of Protection, HRW Vol. 15, No. 1(E), February 2003.

5 Human Rights Watch, “Egypt: Crackdown on Homosexual Men Continues,” October 7, 2003.

6 Human Rights Center for the Assistance of Prisoners Press Release, “Citizen dies while in the State Security station in Ebsheway, Governorate of Al-Fayoum,” September 22, 2003.

7 The Association for Human Rights Legal Aid Press Release, “The series of torture continues,” September 30, 2003.

8 Egyptian Organization for Human Rights Press Release, “EOHR calls for investigating the death of a citizen in the office of the State Security Investigations in Gaber Ibn Hayaan,” November 6, 2003.

9 EOHR Press Release, November 6, 2003: http://www.eohr.org/press/2003/8-1103.htm

10 U.N. Committee against Torture, Summary Record of the 385th meeting, May 14, 1999, U.N. doc. CAT/C/SR.385, Para. 11.

11 According to the Egyptian Human Rights Center for the Assistance of Prisoners in the majority of cases of torture, torture victims “prefer not to file lawsuit either due to fear of the perpetrators or to their relief at being released from the hell they experienced.” Torture in Egypt: A Judicial Reality, HRCAP, March 18, 2001, page 27.

12 In 2000, only in four cases were victims of torture awarded compensation. The sum of awards ranged between 2,000 to 10,000 Egyptian pounds ($570 to 2,860 U.S.). The government told the Committee against Torture in 2001 that a total of seventeen compensation awards were made to victims in the period between 1997-2000.

13 United Nations, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Committee against Torture: Egypt, CAT/C/CR/29/4, December 23, 2002; United Nations, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Egypt, CCPR/CO/76/EGY, November 28, 2002; United Nations Economic and Social Council; Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture to the Commission on Human Rights, Question of the Human Rights of all persons subjected to any form of detention or imprisonment, in particular: Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, E/CN.4/1996/35, January 9, 1996.

14 See, for example: Anthony Shadid, “America Prepares the War on Terror: U.S., Egypt Raids Caught Militants,” Boston Globe, October 7,2001; Rajiv Chandrasekaran and Peter Finn, “U.S. Behind Secret Transfer of Terror Suspects,” Washington Post, March 11, 2002; Anthony Shadid, “In Shift, Sweden Extradites Militants to Egypt,” Boston Globe, December 31, 2001.