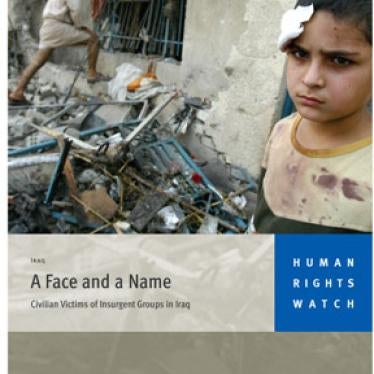

Adil abd al Karim al Kawwaz was driving home from his in-laws' house in Baghdad one night in August with his wife and four kids. It was dark, and he couldn't see the American soldiers from the 1st Armored Division operating a checkpoint with armored vehicles and heavy-caliber guns. No signs or lights were visible, and he did not understand that he was supposed to stop. So he drove a bit too close and the soldiers opened fire, killing him along with three of his children, the youngest of whom was 8 years old.

Such accidents are no longer rare in Iraq. They occur at checkpoints, during raids or after roadside attacks as edgy U.S. soldiers resort with distressing speed to lethal force. Even when they have good reason to shoot, soldiers sometimes respond in an excessive and indiscriminate way that puts civilians unnecessarily at risk.

The U.S. military does not keep statistics on the civilian deaths it has caused, saying it is "impossible for us to maintain an accurate account." But in two weeks of research last month, Human Rights Watch confirmed the deaths of 20 Iraqi civilians in Baghdad at the hands of American troops since the end of major combat operations in May. In total, we collected reports of 94 civilian deaths in Baghdad involving questionable legal circumstances that warrant investigation.

U.S. soldiers are hot, tired and homesick. They face attacks every day from an increasingly organized resistance that melds into the local population and does not care about civilians.

But that doesn't mean that coalition forces should be allowed to operate with near total impunity, as they currently are. They are exempt from Iraqi law, and the military is not adequately investigating allegations of abuse. Thus far, the military has publicly announced only five completed investigations into civilian deaths in Iraq. In each case, the soldiers who fired were found to have operated within the rules of engagement.

I re-investigated two of the five incidents and found evidence to suggest the contrary -- that, in fact, excessive force had been used. In one, which occurred Aug. 9, soldiers from the 1st Armored Division mistakenly shot at an unmarked Iraqi police car as it chased criminals in a van. The Americans killed two Iraqi police officers. A witness said one of the officers was killed after he had stepped out of his car with his hands raised, shouting "No -- police!" A third police officer in the car was beaten by the Americans.

The second case was the shooting of the Kawwaz family on Aug. 7, which the military called "a regrettable incident" but ultimately determined had been within the rules of engagement.

Our research, however, revealed that the troops used overwhelming firepower on a family without first firing warning shots. The U.S. military gave the Kawwaz family $11,000 "as an expression of sympathy."

There are numerous other complaints against U.S. troops these days, including many that do not involve civilian deaths. When I waited in Baghdad three weeks ago to see a legal officer from the 82nd Airborne Division at his base, two Iraqi lawyers were with me at the gate, both with armloads of complaints against U.S. soldiers. The legal officer told me that his brigade alone had received more than 700 complaints against U.S. troops, ranging from property damage to car accidents to beatings to killings.

The military's public affairs office later told me it had paid out $901,545 in compensation for a variety of offenses committed by American troops.

But this is not about money. The excessive behavior of American soldiers is creating animosity at least, and possibly even new recruits for the resistance. Not only individuals but whole tribes are swearing revenge, according to the interviews we conducted.

Part of the problem is the reliance on combat troops to perform post-conflict policing tasks for which they are not prepared. Soldiers from the 82nd Airborne or the 1st Armored Division are trained to fight wars -- not to control crowds, pursue thieves or root out insurgents.

Some military officials recognize the problem and have ordered extra training for combat troops. But as of now, the danger still exists.

I met many Iraqis during my visit who were hopeful the U.S. would help build a democratic Iraq. But many were dismayed by the cultural insensitivity and aggression of some U.S. troops that were alienating Iraqis day by day.

"I wish Saddam would return and kill all Americans," Adil abd al Karim al Kawwaz's distraught wife, Anwar, told a journalist a few days after the U.S. soldiers had killed her husband and three of their children.

Her view is not shared by many, but the number is growing with each civilian killed.