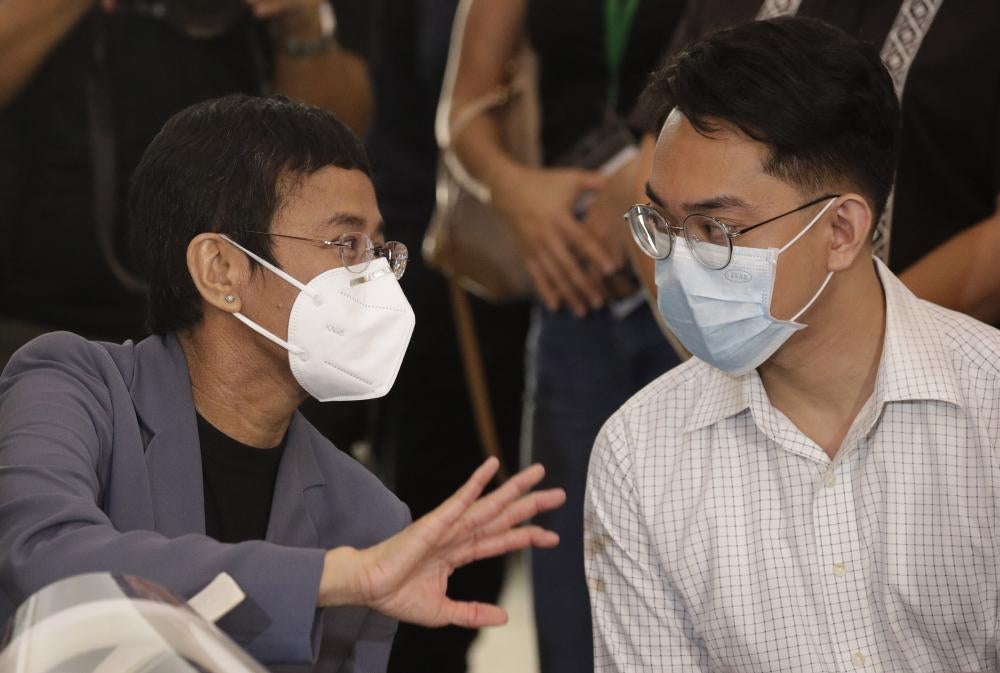

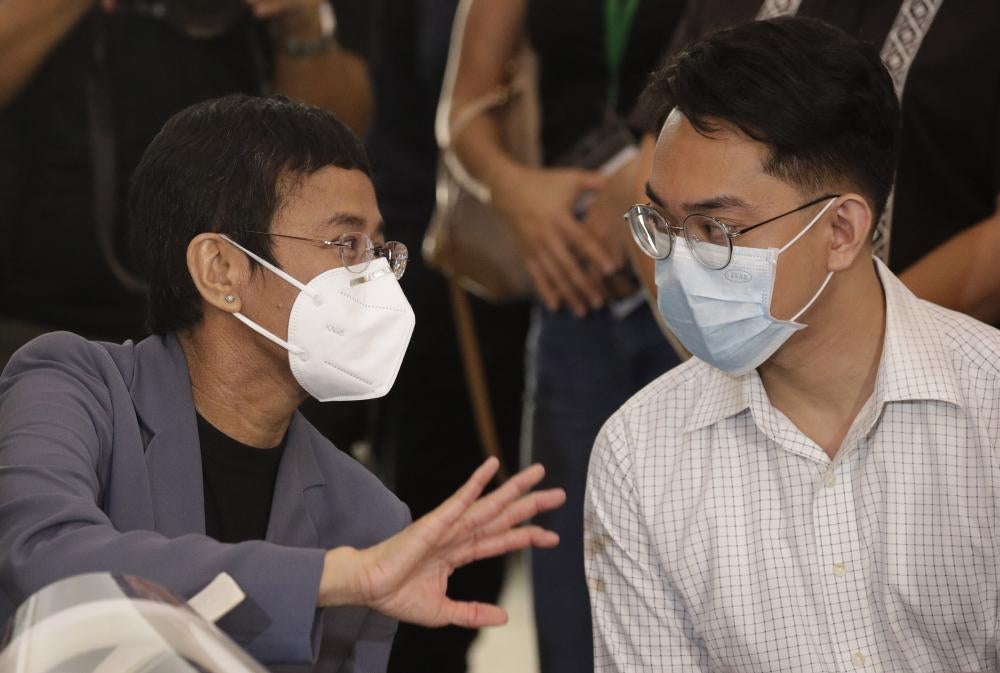

In a devastating blow to freedom of the media in the Philippines, Maria Ressa, the founder and executive editor of Rappler, and Rappler researcher Reynaldo Santos, Jr., were convicted in June 2020 of criminal libel under the Cybercrime Prevention Act. The conviction came after Ressa and Santos published a piece accusing then-Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona of impropriety for using a vehicle owned by a businessman. The prosecution was one of several instigated by President Rodrigo Duterte’s government to stifle Rappler’s critical reporting, particularly on the government’s murderous “war on drugs,” which has killed tens of thousands of people since July 2016.

© 2020 AP Photo/Aaron Favila

In a devastating blow to freedom of the media in the Philippines, Maria Ressa, the founder and executive editor of Rappler, and Rappler researcher Reynaldo Santos, Jr., were convicted in June 2020 of criminal libel under the Cybercrime Prevention Act. The conviction came after Ressa and Santos published a piece accusing then-Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona of impropriety for using a vehicle owned by a businessman. The prosecution was one of several instigated by President Rodrigo Duterte’s government to stifle Rappler’s critical reporting, particularly on the government’s murderous “war on drugs,” which has killed tens of thousands of people since July 2016.

© 2020 AP Photo/Aaron Favila

Saudi Arabian blogger and editor Ra’if Badawi was sentenced to 1,000 lashes and 10 years in prison in 2014 after he was prosecuted on various vague charges, including under the country’s anti-cybercrime law. The court convicted Badawi of undermining general security and ridiculing Islamic religious figures. It followed allegations that his blog was “infring[ing] on religious values” by providing a platform for open debate of views on religion and religious figures. Badawi remains in prison despite international calls for his release.

© 2016 Dinendra Haria/Alamy Stock Photo

Saudi Arabian blogger and editor Ra’if Badawi was sentenced to 1,000 lashes and 10 years in prison in 2014 after he was prosecuted on various vague charges, including under the country’s anti-cybercrime law. The court convicted Badawi of undermining general security and ridiculing Islamic religious figures. It followed allegations that his blog was “infring[ing] on religious values” by providing a platform for open debate of views on religion and religious figures. Badawi remains in prison despite international calls for his release.

© 2016 Dinendra Haria/Alamy Stock Photo

On June 3, 2020 Mauritanian authorities arrested Eby Ould Zeidane, a journalist and member of the Advertising Regulatory Authority, over a Facebook post calling for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan to be observed on fixed dates according to the Gregorian calendar, contrary to Muslim tradition. He was charged with blasphemy under penal code article 306, which carries the death sentence, and for “publishing leaflets that undermine the values of Islam” under article 21 of the Cybercrime Law. Zeidane was released shortly after his arrest and publicly repented his remarks after meetings with religious scholars and the minister of Islamic affairs.

© Private

On June 3, 2020 Mauritanian authorities arrested Eby Ould Zeidane, a journalist and member of the Advertising Regulatory Authority, over a Facebook post calling for the Muslim holy month of Ramadan to be observed on fixed dates according to the Gregorian calendar, contrary to Muslim tradition. He was charged with blasphemy under penal code article 306, which carries the death sentence, and for “publishing leaflets that undermine the values of Islam” under article 21 of the Cybercrime Law. Zeidane was released shortly after his arrest and publicly repented his remarks after meetings with religious scholars and the minister of Islamic affairs.

© Private

Jordanian journalist Tayseer al-Najjar was sentenced to three years in prison in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in March 2017 under article 29 of the UAE cybercrime law for “insulting the state’s symbols on Facebook.” The conviction violated al-Najjar’s rights to free expression and to a fair trial. He was released on December 13, 2018 and returned to Jordan, but in early 2021 he passed away from health complications exacerbated by his experience in prison in the UAE.

© Private

Jordanian journalist Tayseer al-Najjar was sentenced to three years in prison in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in March 2017 under article 29 of the UAE cybercrime law for “insulting the state’s symbols on Facebook.” The conviction violated al-Najjar’s rights to free expression and to a fair trial. He was released on December 13, 2018 and returned to Jordan, but in early 2021 he passed away from health complications exacerbated by his experience in prison in the UAE.

© Private

Mauritanian activist Abdallahi Salem Ould Yali was jailed in January 2018 on charges of incitement to violence and racial hatred for WhatsApp messages calling on Haratines, the ethnic group to which he belongs, to resist discrimination and demand their rights. Authorities accused Yali under the penal code, the 2015 cybercrimes law, and the 2010 counterterrorism law of incitement to racial hatred and violence. Authorities dropped charges and released Yali in February 2019.

© 2017 Private

Mauritanian activist Abdallahi Salem Ould Yali was jailed in January 2018 on charges of incitement to violence and racial hatred for WhatsApp messages calling on Haratines, the ethnic group to which he belongs, to resist discrimination and demand their rights. Authorities accused Yali under the penal code, the 2015 cybercrimes law, and the 2010 counterterrorism law of incitement to racial hatred and violence. Authorities dropped charges and released Yali in February 2019.

© 2017 Private

Prominent Saudi women's rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul was sentenced in December 2020 to nearly six years in prison for several offenses tied to her peaceful activism, including under the country’s cybercrime law, which prohibits “producing something that harms public order, religious values, public morals, the sanctity of private life, or authoring, sending, or storing it via an information network.” She was released in February 2021 but is banned from travel and has a suspended sentence, which allows the authorities to return her to prison at any time for any perceived criminal activity.

© Abaca Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Prominent Saudi women's rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul was sentenced in December 2020 to nearly six years in prison for several offenses tied to her peaceful activism, including under the country’s cybercrime law, which prohibits “producing something that harms public order, religious values, public morals, the sanctity of private life, or authoring, sending, or storing it via an information network.” She was released in February 2021 but is banned from travel and has a suspended sentence, which allows the authorities to return her to prison at any time for any perceived criminal activity.

© Abaca Press/Alamy Stock Photo

In August 2019, a Ugandan court convicted and sentenced academic and activist Stella Nyanzi to 18 months’ imprisonment for “cyber harassment” under the Computer Misuse Act for a poem she published on Facebook in 2018 criticizing President Yoweri Museveni. The court ruled that the poem violated prohibitions on “obscene, lewd, lascivious or indecent” content. In February 2020, a high court judge ruled that Nyanzi’s right to a fair trial was violated and revoked her sentence. Nyanzi fled to Kenya to seek asylum in February 2021 citing several abductions of people close to her as the reason for her decision to flee.

© 2019 AP Photo/Ronald Kabuubi

In August 2019, a Ugandan court convicted and sentenced academic and activist Stella Nyanzi to 18 months’ imprisonment for “cyber harassment” under the Computer Misuse Act for a poem she published on Facebook in 2018 criticizing President Yoweri Museveni. The court ruled that the poem violated prohibitions on “obscene, lewd, lascivious or indecent” content. In February 2020, a high court judge ruled that Nyanzi’s right to a fair trial was violated and revoked her sentence. Nyanzi fled to Kenya to seek asylum in February 2021 citing several abductions of people close to her as the reason for her decision to flee.

© 2019 AP Photo/Ronald Kabuubi

In August 2019 Nigerian Department of State Security operatives arrested Omoyele Sowore, a 2019 presidential candidate and publisher of the New York-based Nigerian news website Sahara Reporters, accusing him under Nigeria’s Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention) Act of planning an insurrection aimed at a forceful takeover of government through his calls for nationwide protests tagged “Revolution Now.”

© 2019 Reuters/Afolabi Sotunde

In August 2019 Nigerian Department of State Security operatives arrested Omoyele Sowore, a 2019 presidential candidate and publisher of the New York-based Nigerian news website Sahara Reporters, accusing him under Nigeria’s Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention) Act of planning an insurrection aimed at a forceful takeover of government through his calls for nationwide protests tagged “Revolution Now.”

© 2019 Reuters/Afolabi Sotunde

Mubarak Bala, president of the Nigerian Humanist Association, was arrested on April 28, 2020 and held incommunicado for a comment on his Facebook page that compared the Prophet Muhammad to a Nigerian Evangelical preacher. The authorities contended that he had violated Nigeria’s cybercrimes law, which criminalizes insult of people based on their religion. They also alleged that the posts were contrary to the Kano State penal code, which sets punishments of up to two years in prison for public insults or contempt of any religion likely to lead to a breach of peace. Bala is in police custody but was only allowed access to his lawyers in October 2020. A petition challenging his detention and prosecution in Kano State is currently before a Federal High Court in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital.

© 2021 Kola Sulaimon/AFP via Getty Images

Mubarak Bala, president of the Nigerian Humanist Association, was arrested on April 28, 2020 and held incommunicado for a comment on his Facebook page that compared the Prophet Muhammad to a Nigerian Evangelical preacher. The authorities contended that he had violated Nigeria’s cybercrimes law, which criminalizes insult of people based on their religion. They also alleged that the posts were contrary to the Kano State penal code, which sets punishments of up to two years in prison for public insults or contempt of any religion likely to lead to a breach of peace. Bala is in police custody but was only allowed access to his lawyers in October 2020. A petition challenging his detention and prosecution in Kano State is currently before a Federal High Court in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital.

© 2021 Kola Sulaimon/AFP via Getty Images

Fahad al-Fahad was recently released from prison after serving a five-year prison sentence in Saudi Arabia. In April 2016 he was arrested and subsequently convicted on charges tied solely to his peaceful social media activity. Al-Fahad’s charges included violating the Saudi cybercrime law via tweets criticizing the Saudi criminal justice system and government corruption and “inciting hostility against the state, its structure, and its justice systems.” He is one of many prominent Saudi activists serving long prison terms on charges such as “breaking allegiance with the ruler” or “inciting hostility against the state” that do not constitute recognizable crimes under international law.

© 2018 Raif Badawi Foundation

Fahad al-Fahad was recently released from prison after serving a five-year prison sentence in Saudi Arabia. In April 2016 he was arrested and subsequently convicted on charges tied solely to his peaceful social media activity. Al-Fahad’s charges included violating the Saudi cybercrime law via tweets criticizing the Saudi criminal justice system and government corruption and “inciting hostility against the state, its structure, and its justice systems.” He is one of many prominent Saudi activists serving long prison terms on charges such as “breaking allegiance with the ruler” or “inciting hostility against the state” that do not constitute recognizable crimes under international law.

© 2018 Raif Badawi Foundation

Waleed Abu al-Khair is a lawyer and the founder of the group Monitor of Human Rights in Saudi Arabia. In 2009 Abu al-Khair acted as defense lawyer for a member of the "Jeddah reformists," a group of 16 men, including political and human rights activists, whom police detained after they met to establish a human rights organization. A judge ordered his detention in April 2014 and a Saudi court eventually sentenced him to 15 years in prison, including for violating a cybercrime law, solely for his peaceful human rights advocacy.

© 2013 Human Rights Watch

Waleed Abu al-Khair is a lawyer and the founder of the group Monitor of Human Rights in Saudi Arabia. In 2009 Abu al-Khair acted as defense lawyer for a member of the "Jeddah reformists," a group of 16 men, including political and human rights activists, whom police detained after they met to establish a human rights organization. A judge ordered his detention in April 2014 and a Saudi court eventually sentenced him to 15 years in prison, including for violating a cybercrime law, solely for his peaceful human rights advocacy.

© 2013 Human Rights Watch

Saudi prosecutors are seeking the death penalty against a Saudi religious reformist thinker, Hassan Farhan al-Maliki, on a host of vague charges relating to his peaceful religious ideas, including an allegation that he defamed a Kuwaiti man by accusing him on Twitter of supporting the Islamic State (ISIS) and violating Saudi Arabia’s cybercrime law. Saudi authorities arrested him in September 2017, brought charges against him in October 2018, and have detained him since.

© 2014 Hassan al-Maliki/Youtube

Saudi prosecutors are seeking the death penalty against a Saudi religious reformist thinker, Hassan Farhan al-Maliki, on a host of vague charges relating to his peaceful religious ideas, including an allegation that he defamed a Kuwaiti man by accusing him on Twitter of supporting the Islamic State (ISIS) and violating Saudi Arabia’s cybercrime law. Saudi authorities arrested him in September 2017, brought charges against him in October 2018, and have detained him since.

© 2014 Hassan al-Maliki/Youtube

Abdulrahman al-Sadhan is a former Saudi Red Crescent employee who was detained by Saudi authorities in March 2018 after his anonymous Twitter account is believed to have been breached by the Saudi government. Authorities held him incommunicado with no contact with the outside world for nearly two years before allowing one brief phone call in February 2020. Saudi Arabia’s Specialized Criminal Court convicted him on a host of vague charges, including violating the country’s cybercrime law, in March 2021, and sentenced him to 20 years in prison.

© Private

Abdulrahman al-Sadhan is a former Saudi Red Crescent employee who was detained by Saudi authorities in March 2018 after his anonymous Twitter account is believed to have been breached by the Saudi government. Authorities held him incommunicado with no contact with the outside world for nearly two years before allowing one brief phone call in February 2020. Saudi Arabia’s Specialized Criminal Court convicted him on a host of vague charges, including violating the country’s cybercrime law, in March 2021, and sentenced him to 20 years in prison.

© Private

In April 2019, Ola Bini, a Swedish programmer and internet activist, was arrested in Ecuador after that country’s Minister of Government María Paula Romo claimed that a group of Russians and Wikileaks-connected hackers were in the country "cooperating with attempts to destabilize the government." Romo spoke hours after the government had ejected Julian Assange from Ecuador's London Embassy, and accused the hackers of planning an attack in retaliation for the eviction. No further details of this alleged sabotage plot were ever revealed. A court ordered Bini’s release from pre-trial detention 70 days later. He is facing a travel ban, preventing him from leaving Ecuador, as an alternative measure, and authorities are still holding devices that they confiscated from him. Bini was subsequently charged with “unauthorized access to an information system.” His case has not yet been tried and has experienced several procedural irregularities.

© 2019 AP Photo/Dolores Ochoa

In April 2019, Ola Bini, a Swedish programmer and internet activist, was arrested in Ecuador after that country’s Minister of Government María Paula Romo claimed that a group of Russians and Wikileaks-connected hackers were in the country "cooperating with attempts to destabilize the government." Romo spoke hours after the government had ejected Julian Assange from Ecuador's London Embassy, and accused the hackers of planning an attack in retaliation for the eviction. No further details of this alleged sabotage plot were ever revealed. A court ordered Bini’s release from pre-trial detention 70 days later. He is facing a travel ban, preventing him from leaving Ecuador, as an alternative measure, and authorities are still holding devices that they confiscated from him. Bini was subsequently charged with “unauthorized access to an information system.” His case has not yet been tried and has experienced several procedural irregularities.

© 2019 AP Photo/Dolores Ochoa