OVERVIEW:

Strengthening the Right to Free Education

The Issue

- For millions of children around the world, the cost of schooling remains one of the most significant barriers to education, particularly at the pre-primary and secondary level.

- Approximately 88 percent of children worldwide complete primary school; but less than 60 percent complete secondary school and nearly half of all children miss out on early childhood education.[1]

- Existing international law guarantees children free and compulsory primary education, but the Convention on the Rights of the Child says nothing explicit about early childhood education and does not oblige states to guarantee every child free secondary education.

The Goal

- A new optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, enshrining an explicit right to early childhood care and education; to free public pre-primary education, beginning with at least one year; and to free public secondary education—consistent with the right to free primary education.

Why this is possible

- Consensus already exists. All governments have already pledged through the Sustainable Development Goals to provide all children with access to pre-primary and ensure all children complete free secondary education.

- At least 107 countries guarantee at least one year of free pre-primary in their domestic law, and approximately 117 guarantee at least 11 years of free primary and secondary, providing a strong foundation for stronger international standards.

The Benefit for Children

- Stronger international law can accelerate far-reaching changes in national law, policy, and practice and could advance the rights of millions of children.

- Greater access to free education will help reduce poverty and inequality, contribute to inclusive and sustainable societies, empower girls, and help children thrive.

- Education underpins the realization of children’s other rights, including their right to health, to an adequate standard of living, and protection from abuse and harm.

What’s Next

- In July 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Council agreed by consensus to begin a process to explore and elaborate the proposed protocol. The resolution was advanced by Luxembourg, the Dominican Republic, and Sierra Leone, and co-sponsored by 49 states from all regions of the world. All governments should support the protocol when negotiations begin in 2025.

Q&A:

Strengthening the Right to Free Education through a new Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child

In July 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Council agreed by consensus to begin a process to explore and elaborate an optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child with the aim to explicitly recognize that the right to education includes early childhood care and education, and to guarantee free public pre-primary education (beginning with one year) and free public secondary education for all children. The resolution was advanced by Luxembourg, the Dominican Republic, and Sierra Leone, and co-sponsored by 46 other states from all regions of the world. This Q&A explores common questions about the proposed protocol.

Q: Why should the right to education be strengthened under international law?

A: Education is fundamental to children’s development and a powerful catalyst for improving children’s lives. Children who are in school enjoy better health, better job prospects, higher earnings as adults, and are less vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, including child labor and child marriage. Simply put, education is one of the best investments societies can make—both for children and for their communities.

While the Convention on the Rights of the Child guarantees all children free and compulsory primary education, it does not require states to make secondary education free for all children, and it makes no explicit reference to early childhood education or pre-primary education. Yet free primary education alone is clearly insufficient to prepare children to succeed in today’s world.

Primary completion rates have increased steadily, if slowly, over recent decades. According to the latest UNESCO data, an estimated 88 percent of children worldwide complete primary school.[2] Yet secondary completion rates lag behind, with only 59 percent of children globally completing secondary school.[3] At the pre-primary level, nearly half of all children miss out on early childhood education.[4]

The disparities between high-income and low-income countries are even more stark. In low-income countries, only one in five young children attend pre-primary education programs.[5] In high-income countries, children are more than twice as likely to attend secondary school as those in low-income countries (92 percent vs. 39 percent).[6]

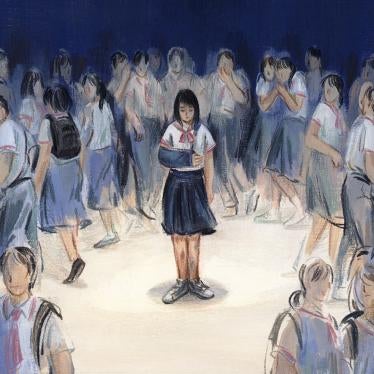

The cost of education remains a significant barrier for millions of children around the world, particularly at the pre-primary and secondary levels[7] where tuition fees, other fees levied by schools and indirect costs such as transportation drive inequality in access. In many contexts, gender inequality and discriminatory and harmful social norms lead too many parents with limited financial resources to prioritize boy’s education; girls of secondary school age are negatively affected when those resources are scarce and education-related costs increase due to the levying of fees.

Countries that remove school fees can experience substantial increases in enrollment and completion rates.[8] For example, countries that offer at least two years of free pre-primary education have participation rates, on average, that are 15 percentage points higher than countries with no free pre-primary.[9] Just one year of free and compulsory pre-primary education is associated with a 12 percentage points increase in primary school graduation rates for those countries with the lowest rates of primary completion, which are primarily low- and lower-middle-income countries.[10] Similarly, low and lower-middle income countries that guarantee free secondary education have completion rates approximately 24 percentage points higher than those that do not guarantee free secondary.[11]

Children’s access to pre-primary and secondary education should not be determined by their parents’ willingness or ability to pay. Accepting such a situation violates the rights to equality and non-discrimination; jeopardizes children’s rights to health, development, and survival; and conflicts with the CRC’s overarching obligation on states that “in all actions concerning children … the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”[12]

Q: The CRC already guarantees the right to education for all children (article 28), without discrimination (article 2). Aren’t these standards enough to guarantee free education for every child?

A: The CRC, like all human rights treaties, is to be viewed as a living instrument,[13] whose interpretation develops over time. Yet the language in the CRC and other human rights treaties, singling out free education only at the primary level and applying “progressive realization” to education more generally,[14] may give rise to ambiguity in states’ obligations. Therefore, updating the language in key international texts on education is important to bring clarity and certainty to the evolving nature of states’ obligations in line with developments in the right to education.

In practice, the requirement of progressive realization to deliver free pre-primary and free secondary has not resulted in the desired outcome of full universal free education for every child. Thirty-five years after the adoption of the CRC, and 70 years after the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (which similarly only guarantees free education “at least in the elementary and fundamental stages”), enrollment and completion rates for pre-primary and secondary education still lag behind primary. Even some of the world’s wealthiest countries do not yet provide all levels of education for children without cost.

To advance the rights of children, international texts on the right to education should explicitly recognize a right to early childhood education, and guarantee children the right to free pre-primary education, beginning with one year, and free secondary education, with the same urgency as the right to free primary education.

Q: Why is free pre-primary and free secondary education so important?

A: A growing body of research has found that early childhood learning can have profound long-term benefits for children’s cognitive and social development, educational attainment, health, and employment prospects. The pace of children’s brain development is at its highest in the first years of life, so this period represents a critical opportunity to make a positive difference in children’s lives.[15]

Multiple studies have found that access to early childhood education can mitigate inequalities among children from families of different incomes. Universal access to quality pre-primary education narrows early achievement gaps for children from disadvantaged households and places them on a more equal footing with their well-off peers.[16] According to the International Monetary Fund, increasing low pre-primary enrollment can yield “large positive returns over an individual’s entire lifetime, particularly for the most disadvantaged.”[17]

Inclusive pre-primary and secondary education can particularly benefit children with disabilities, including by promoting inclusion in education settings from the early years, building children’s learning foundations and tackling learning barriers, promoting their enrollment and attendance, and reducing stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes against them.[18]

Secondary education is increasingly important for children’s success in today’s world. Children with secondary education are more likely to find work as adults, earn more, and escape or avoid poverty, contributing to reducing inequality.[19] Every additional year of secondary education reduces adolescent mortality by up to 17 percent.[20] Adolescents who complete secondary school are less likely to experience child rights violations like the worst forms of child labor, child marriage, trafficking, and recruitment by armed groups.[21]

Quality secondary education, including technical and vocational training, can empower young people with knowledge and skills needed for sustainable development, including citizenship and human rights, and access to essential information to protect their health and well-being.[22]

Q: UN member states have already committed to providing access to pre-primary education and ensuring that all children complete free secondary education as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Are additional international legal texts really needed?

A: As part of the Sustainable Development Goals, all UN member states have committed to ensure that by 2030, all girls and boys complete free, equitable, and quality secondary education and have access to quality early childhood development, care, and pre-primary education.[23] The 2015 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action adopted by UNESCO member states encourages states to achieve this last target by providing “at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary education of good quality.”[24]

The inclusion of pre-primary education and free secondary education in the SDGs reflects countries’ acknowledgement that these are essential to children’s development and a sustainable future for all, and a broad international consensus in favor of obligations to provide pre-primary education and free secondary education. While the SDGs are significant political commitments, they do not have the force of law. Countries report on their progress through voluntary national reviews, but there is no formal mechanism for children to claim redress if governments fail to deliver on their promises, nor a plan for ensuring continued progress is made past the year 2030. In contrast, stronger legal standards would have the force of law, be subject to independent monitoring mechanisms (e.g. through reviews by the Committee on the Rights of the Child), and need not be limited to a specific time period.

Q: Why an Optional Protocol to the CRC? Aren’t there other options to reinforce the right to education?

A: The Committee on the Rights of the Child could provide relevant, contemporary interpretation on the right to education by updating existing General Comments or issuing a new General Comment on the right to education. It can also consider individual complaints on the right to education through the CRC’s 3rd Optional Protocol on a communications procedure. In its concluding observations, the committee can—and has—called on states parties to expand access to pre-primary and free secondary education.[25] These mechanisms, however, do not carry the same immediate weight of hard treaty law. A legally-binding treaty would definitively articulate explicit rights to early childhood education and to free public pre-primary and secondary education.

Other options for a new international treaty could include a new UNESCO treaty or an Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).[26] UNESCO has three existing global education conventions;[27] however, these are monitored by states themselves, providing a less robust and independent compliance mechanism than the treaty bodies for the CRC and ICESCR, which are made up of independent experts. The CRC already has two subject-matter-based protocols, while the ICESCR has none. Historically, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has given significantly more attention to education issues in its concluding observations than the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[28] In addition, the nearly universal ratification of the CRC provides the widest basis of support for enhanced compliance.

Q: Aren’t there other children’s rights issues that also need stronger international law? Why should a new optional protocol focus on education rather than other important issues?

A: The number of children that would benefit from strong guarantees of rights to free pre-primary and secondary education is enormous: An estimated 175 million children are not enrolled in pre-primary education. An estimated 181 million children and older adolescents of secondary school age are not enrolled.[29] Failure to address these gaps affects not only these children but also has repercussions for hundreds of millions more in future years.

Education has a multiplier effect, enabling children to realize the full range of their rights, including their rights to cognitive and social development, to health, to an adequate standard of living, protection from exploitation and abuse, and preparation for responsible participation in society.

Given the scale of children affected and the far-reaching benefits of a stronger right to education, addressing these gaps in the Convention on the Rights of the Child should be an urgent priority.

Q: What were the negotiation and drafting processes of the previous protocols to the Convention on the Rights of the Child?

A: The Convention on the Rights of the Child currently has three optional protocols. For each, member states introduced resolutions at the UN Human Rights Council and its predecessor, the Commission on Human Rights, that established open-ended inter-sessional working groups open to all member states to consider and negotiate the new instruments. In 1994, the Commission on Human Rights established two separate open-ended working groups to create optional protocols related to the sale of children, child prostitution, and child pornography, and to address children’s involvement in conflict.[30] In 2009, the Human Rights Council established an open-ended working group to draft and present a third Optional Protocol on communication procedures.[31] Once agreed in Geneva, the protocols were adopted by the UN General Assembly, and then opened for ratification.

Q: Developing new international law takes such a long time. Is it worth it?

A: The process for the CRC’s first two optional protocols took approximately six years.[32] The third optional protocol, establishing an individual complaints mechanism, took two years.[33]

Once adopted, however, binding international treaties can accelerate far-reaching changes in national law, policy, and practice. For example, in the decade following the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the involvement of children in armed conflict, nearly twenty countries adopted or amended national legislation to raise their minimum age of voluntary recruitment to at least 18.[34] Since ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers was adopted in 2011, more than 70 countries have strengthened labor protections for domestic workers, improving the lives of millions of people.[35]

Q: What support is there for a new optional protocol to explicitly guarantee free pre-primary and free secondary education?

A: A range of international experts, including former chairs of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, former heads of UNICEF and UNESCO, former UN high commissioners for human rights, Nobel Peace Prize laureates, and other luminaries have explicitly called for such an optional protocol.[36] In advance of the 2022 Transforming Education Summit, over 500,000 global citizens signed an open letter led by Malala Yousafzai and Vanessa Nakate, calling for a global treaty to enshrine the right to free education from pre-primary through secondary.[37] In June 2024, 70 leading scholars from 30 countries called for a new international treaty to recognize children’s rights to free early childhood education and free secondary education, stating that international law has not kept pace with research showing the benefits of education.[38]

In 2022, the then-Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education recommended to the UN General Assembly that the right to early childhood education should be enshrined in a legally-binding human rights instrument.[39] In 2024, UNESCO and UNICEF jointly published the first global report on early childhood care and education (ECCE), stating that “extending the right to education to include the right to ECCE could be an important policy lever to accelerate progress on all targets under SDG Target 4.2.”[40]

A growing group of civil society partners also support the optional protocol, including more than 20 international and regional non-governmental organizations working on the right to education, children’s rights, and gender equality.

Q: Isn’t free pre-primary and free secondary education financially out of reach for many countries?

A: States have the obligation to realize rights to the maximum of their available resources, including through international cooperation, and it is now feasible in the short-term to achieve free pre-primary and secondary education for all. Global per capita GDP has more than doubled since 1966, when the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights established that states have an obligation to progressively realize the right to free secondary education.[41] In low- and middle-income countries, GDP per capita has more than quadrupled over that period.[42]

A range of low and low-middle-income countries have demonstrated that with political will, they can mobilize the resources needed to ensure free education for all children. Sierra Leone, for example, adopted a new education law in 2023 that guarantees 13 years of free schooling, from one year of pre-primary through secondary school, and devotes 22 percent of its national budget to education.[43] Eighteen low or low-middle income countries have already guaranteed at least one year of free pre-primary education in their national law, and 19 have guaranteed free secondary.[44] Low- and lower-middle income countries that increased the number of years of free or compulsory pre-primary education guaranteed in their legislation since 2015 include: Comoros, Jordan, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mongolia, Nepal, Palestine, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.[45]

Studies show that investing in universal free pre-primary education can result in significant cost savings by reducing repetition rates at the primary and secondary level. Children who do not attend pre-primary school often end up repeating grades, at significant cost to the government. Research from sub-Saharan African countries suggests that investments in early childhood care and education would be offset by up to 87 percent because of higher efficiency within primary education alone.[46]

Expanding free pre-primary schooling can also increase the employment, earnings, and productivity of parents, including by allowing parents—particularly mothers—to enter or re-enter the workforce earlier.[47] A number of studies have found that access to early childhood care and education programs increase mothers’ income and labor force participation, and contribute to gender equality.[48]

Extra domestic financing for education can be obtained by widening a country’s tax base, improving governance and accountability, eliminating illicit financial flows and tax evasion, using fiscal and foreign exchange reserves, managing debt by borrowing or restructuring existing debt, developing and adopting an accommodating macroeconomic framework, and re-allocating public expenditures.[49]

Even so, many low-income countries will need international assistance. States parties to the ICESCR and CRC have obligations to provide international cooperation to realize economic, social and cultural rights, including specific obligations with regard to education under article 28.3 of the CRC.[50] UNESCO estimates that the entire funding gap for free pre-primary, primary, and secondary education could be filled if 40 higher-income donor countries[51] met the global target of dedicating 0.7 percent of their gross national income to aid and allocated 10 percent of that aid to pre-primary through secondary education.

Over the long-term, education investments pay for themselves many times over. For example, a simulation model of the potential long-term economic effects of increasing preschool enrollment to 50 percent in every low- and middle-income country found that every dollar invested in pre-primary education could yield up to US$16 in social and economic benefits, including reduced primary school repetition rates, improved lifetime earnings, new employment opportunities, and gains from freeing up the time of primary caregivers.[52]

Free secondary education also provides enormous societal dividends and contributes to economic growth. UNESCO estimates that if all adults completed secondary education, global poverty rates would be reduced by half, lifting 420 million people out of poverty, two-thirds of them in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.[53]

Q: Wouldn’t a new Optional Protocol create an unreasonable reporting burden on states and increase the work of the Committee on the Rights of the Child? The CRC has more states parties to monitor than any other human rights treaty and already has three protocols.

A: The committee is under-resourced and member states should prioritize efforts to ensure it receives the resources it needs to conduct its work effectively. In any case, the UN Human Rights Council decided that the working group established to consider the protocol should consider allowing member states to incorporate their reporting into their regular CRC reviews, without a separate, initial report. Indeed, countries that already provide free pre-primary and free secondary education for their children already appear to reflect relevant information in their regular reporting to the committee.

Q: Are governments on board? What happens next?

A: In a resolution adopted in July 2024, the UN Human Rights Council agreed by consensus to “establish an open-ended intergovernmental working group of the Human Rights Council with the mandate of exploring the possibility of, elaborating, and submitting to the Human Rights Council a draft optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child with the aim to: (a) Explicitly recognize that the right to education includes early childhood care and education; (b) Explicitly state that, with a view to achieving the right to education, States shall: (i) Make public pre-primary education available free to all, beginning with at least one year; [and] (ii) Make public secondary education available free to all.”[54]

The resolution was advanced by Luxembourg, the Dominican Republic, and Sierra Leone, and co-sponsored by 46 other states from all regions of the world. Moreover, the resolution contains a historic provision: For the first time, children are to be consulted and participate in the development of this new international law. The working group is expected to begin its work in late 2025.

At least 107 member states already guarantee at least one year of free pre-primary in national law and more than 117 states guarantee free secondary education, providing a solid basis of support once the instrument is adopted and open for ratification.[55]

This is the time to guarantee free, quality and inclusive education for all children, from pre-primary through secondary. No child’s access should be limited by their family's economic situation. Free universal education creates a better future not only for children, but for all.

A TIMELINE OF PROGRESS

Towards an Optional Protocol on Free Education

1980: During advocacy for what was to become the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Poland proposes that international law recognize that the end goal of the right to education was free secondary education for all. Unfortunately, consensus on this target was not achieved.

1989: UNESCO—the UN’s lead education organization—calls for the right to education in the draft Convention on the Rights of the Child to include early childhood education. Countries chose not to adopt this proposal.

2014: Malala Yousafzai and the Malala Fund call on states to include free secondary education in the Sustainable Development Goals.

2015: Adopting the Sustainable Development Goals, states pledge to provide all children with access to pre-primary and ensure all children complete free secondary education.

2015: The Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action calls on states to guarantee at least 1 year of free pre-school and 12 years of free primary and secondary education.

2019: The World Organisation for Early Childhood Education (OMEP) and the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education meet with the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child to share their research from Latin America and the Caribbean, concluding that the legally binding human rights framework failed to adequately specify that the right to education should begin in early childhood, before primary school.

December 2021: UNESCO concludes that recognizing early childhood education as a legal right at the international level “would allow the international community to hold governments accountable and ensure there is adequate investment.”

June 2022: International children’s rights and human rights experts call for a new optional protocol to expand the right to education under international law to recognize every child’s right to free pre-primary education and free secondary education.

September 2022: Over half-a-million people sign an Avaaz open letter from Malala Yousafzai and Vanessa Nakate calling on world leaders to create a new global treaty that protects children’s right to free education—from pre-primary through secondary school.

September 2022: At the UN Transforming Education summit, Argentina and Spain become the first two states to announce commitments to support the idea.

September 2022: The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education recommends to the UN General Assembly that the right to early childhood education should be enshrined in a legally-binding human rights instrument.

November 2022: Education ministers and delegations gathered at the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education in Uzbekistan adopt the “Tashkent Declaration,” in which they agreed to enhance legal frameworks to ensure the right to education “includes the right to at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary quality education for all children.”

June 2023: 73 states from across all regions join a statement led by Luxembourg and the Dominican Republic at the UN Human Rights Council, stating support for “efforts to strengthen the right to education, including the explicit right to full free secondary and at least 1 year of free pre-primary education.” At the same time, Brazil calls on states to consider “a fourth optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child to recognize rights to free pre-primary and free secondary.”

June 2024: 70 eminent scholars from 30 countries call for a new treaty to recognize children’s rights to free pre-primary and free secondary education, saying international law has not kept pace with scientific evidence showing benefits of education.

June 2024: 22 global non-governmental organizations jointly call on UN member states to support a Human Rights Council resolution to create a new optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child to guarantee free education from pre-primary through secondary.

June 2024: UNESCO and UNICEF jointly publish the first global report on early childhood care and education, stating that compliance with countries’ SDG commitments “requires updating existing international normative instruments governing education in order to ensure an explicit guarantee on ECCE rights.”

July 2024: The UN Human Rights Council agrees by consensus to establish an open-ended intergovernmental working group “with the mandate of exploring the possibility of, elaborating, and submitting to the Human Rights Council a draft optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child with the aim to: (a) Explicitly recognize that the right to education includes early childhood care and education; (b) Explicitly state that, with a view to achieving the right to education, States shall: (i) Make public pre-primary education available free to all, beginning with at least one year; [and] (ii) Make public secondary education available free to all.” The resolution contains a historic provision: for the first time, children are to be consulted and participate in the development of this new international law. The resolution is led by Luxembourg, Dominican Republic and Sierra Leone and supported by a core group consisting of Armenia, Bulgaria, Colombia, Cyprus, Gambia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nauru, Panama, and Romania. In total, 49 UN member states co-sponsor the resolution.

INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS:

A Call to Update the International Right to Education

Education is a fundamental human right and one of the most powerful tools for improving children’s lives. Education improves children’s health, their standard of living, protects them from exploitation and abuse, and expands their future opportunities and participation in civic life. It lifts children out of poverty, reduces inequality, and helps build strong, sustainable societies.

Existing international law guarantees the right to education for all but does not explicitly guarantee children’s right to free pre-primary or free secondary education. While an estimated 85 percent of children worldwide complete primary school, only half of the world’s children are enrolled in pre-primary education or complete secondary school.[56] Children from families living in poverty are the least likely to attend, with cost remaining a significant barrier for many.

We believe it is time to update the right to education under international law, and explicitly guarantee children’s right to free pre-primary and free secondary education. It is no longer acceptable that children’s development and future prospects are determined by their families’ ability to pay for education.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought additional urgency to this goal, creating some of the most disastrous consequences for children’s right to education in history. Efforts to build back better education systems should not only remediate this devastation but also ensure that children’s right to education is sufficient for them to thrive in today’s world.

As part of the Sustainable Development Goals, all governments have committed to ensure that by 2030, all girls and boys have access to quality pre-primary education, and free, equitable and quality secondary education. This commitment should be cemented in binding international law.

We support a new optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child that would explicitly guarantees the right to free secondary education and at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary education. Establishing and fulfilling this right will benefit children and societies for generations to come.

Signers:

Vihaan Agarwal (India), International Children’s Peace Prize laureate (2021)

Amal al-Dossari (Bahrain), former member, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Philip Alston (Australia), former Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights

Louise Arbour (Canada), former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

Chernor Bah (Sierra Leone), co-founder, A World At School and Purposeful; former youth advisory group chair, Global Education First Initiative

Carol Bellamy (US), former executive director, UNICEF

Irina Bukova (Bulgaria), former director general, UNESCO

Olivier De Schutter (Belgium), UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights

Solomon Dersso (Ethiopia), African Commission on Human and People’s Rights

Jaap Doek (Netherlands), former chairperson, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Marc Dullaert (Netherlands), former chair, European ombudspersons and commissioners for children

Leonardo Garnier (Costa Rica), Special Advisor of the UN Secretary-General for the Transforming Education Summit

Maria Herzog (Hungary), former member, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein (Jordan), former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

Tawakkol Karman (Yemen), Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (2011)

Theoni Koufonikolakou (Greece), deputy ombuds for children’s rights, Greece

Anthony Lake (United States), former executive director, UNICEF

Yanghee Lee (Republic of Korea), former chairperson, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Moushira Khattab (Egypt), former member, African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and Committee on the Rights of the Child

Lothar Krappmann (Germany), former member, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Koichiro Matsuura (Japan), former director general, UNESCO

Vernor Munoz Villalobos (Costa Rica), former Special Rapporteur on the right to education

Faith Mwangi-Powell (Uganda), CEO, Girls not Brides

Chaeli Mycroft (South Africa), International Children’s Peace Prize laureate (2011)

Salima Namusobya (Uganda), working group on economic, social, and cultural rights, African Commission on Human and People’s Rights

Joseph Ndayisenga (Burundi), former chairperson, African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

Christina Nomdo (South Africa), Western Cape Commissioner for Children, South Africa

Rosa Maria Ortiz (Paraguay), former commissioner on children's rights, InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights

Marta Santos Pais (Portugal), former Special Representative of the Secretary General on Violence against Children

Elina Pekkarinen (Finland), Ombudsman for Children in Finland

Paulo Sergio Pinheiro (Brazil), former Independent Expert of the UN Secretary- General for the World Report on Violence Against Children

Sadat Rahman (Bangladesh), International Children’s Peace Prize laureate (2020)

Kailash Satyarthi (India), Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (2014)

Nevena Vuckovic Sahovic (Serbia), former member, Committee on the Rights of the Child

Yasmine Sherif (Sweden), director, Education Cannot Wait

Jody Williams (United States), Nobel Peace Prize Laureate (1997)

Jean Zermatten (Switzerland), former chairperson, Committee on the Rights of the Child

LEADING SCHOLARS:

Research Supports the Need to Recognize the Right to Free Early Childhood Education and Free Secondary Education

June 2024

We, the undersigned individuals, are scholars, experts, and researchers on the education, development, wellbeing, and rights of children and adolescents. We write to express our support for a new optional protocol to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) focused on the right to free education. The aim of this initiative is to ensure recognition under international law of the right to free early childhood education and free secondary education, alongside the already-existing right to free and compulsory primary education.

Well-established scientific evidence shows unequivocally that education is foundational to children’s healthy development, wellbeing, fulfilment of their full potential, and their lifelong prospects. Not only is education valuable in its own right, it has a multiplier effect—that is, education helps position children to secure their other rights during childhood and subsequently as adults. At a societal level, investing in education is any country’s most effective policy tool to ensure prosperity, social cohesion, and sustainable development.

Although research evidence is clear on the importance of education to children’s holistic development, international law has not kept pace. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—the foundational instrument of the modern human rights movement—recognized every individual has the right to education, mandating that primary education be free and compulsory for all. In the more than 70 years since then, the international law standard on the right to education has changed little. While the right to education has been enshrined in legally-binding treaties—including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966)—international law has not expressly recognized early childhood education (pre-primary education) or mandated free secondary education for all children. These treaties have been silent on early childhood education, while calling on states to make secondary education “available and accessible” but stopping short of requiring that it be made available free. We believe it is time for that to change.

International consensus and frameworks (e.g., the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals) urge access to high-quality early childhood education, which, according to the Committee on the Rights of the Child’s “General Comment No. 7 on Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood”, must be understood as beginning at birth. Similarly, evidence from research on adolescent development reveals the importance of secondary education to children’s healthy development and lifelong prospects, including their capacity to navigate the complexities of our world in the 21st Century.

While the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call on states to ensure all children have access to quality early childhood education and care (SDG 4.2) and free secondary education (SDG 4.1), global monitoring data show the world is far from achieving the 2030 targets. Significant disparities persist among—and within—countries and regions, compounding stark inequalities of access, opportunity, condition, and outcome, especially for children from disadvantaged and marginalized communities. We therefore call for an urgent renewed commitment to education systems that realize just and equitable outcomes for ALL children. And we believe it is essential that this commitment be backed by a legal mandate to ensure its success.

The world has changed dramatically since 1948, and our understanding of how children develop and flourish has advanced significantly. To ensure education systems contribute to realizing children’s rights enshrined in UNCRC, it is critical that we secure their right to education from birth through secondary education.

We, therefore, call on all U.N. member states to support a new optional protocol to the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child that will recognize the importance of education to children’s healthy development by mandating that governments ensure every child has access to free pre-primary[57], primary, and secondary education.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Todres, Distinguished University Professor & Professor of Law, Georgia State University, United States (jtodres@gsu.edu)

Mathias Urban, Desmond Chair of Early Childhood Education, Early Childhood Research Centre, Dublin City University, Ireland (mathias.urban@dcu.ie)

Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Samuel F. and Rose B. Gingold Professor of Human Development and Social Policy, Director, Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy and diversitydatakids.org, The Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, United States

Alejandro Acosta, Member of the Executive Board of the International Network on Peace Building with Young Children, INPB, Colombia

Bruce Adamson, Professor in Practice, University of Glasgow School of Law; Former Children and Young Person’s Commissioner Scotland, United Kingdom

Vina Adriany, Professor of Early Childhood Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia; Director, Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organisation – Center for Early Childhood Care, Education and Parenting (SEAMEO-CECCEP)

Philip Alston, Professor of Law, New York University School of Law, United States

Pramod K. Anand, Visiting Fellow, Research and Information Systems for Developing Countries, New Delhi, India

Marisol Moreno Angarita, Professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Colombia

W. Steven Barnett, Board of Governors Professor, National Institute for Early Education Research, Rutgers University, United States

Klaus D. Beiter, Professor of Law, North-West University, South Africa

Marianne N. Bloch, Professor Emerita, Curriculum & Instruction, Gender and Women's Studies, University of Wisconsin Madison, United States

Richard J. Bonnie, Harrison Foundation Professor Emeritus of Law, Medicine, and Public Policy, Director Emeritus, Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy, University of Virginia School of Law, United States

Tammy Chang, Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, US

Tara M. Collins, Associate Professor, School of Child and Youth Care, Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada; Honorary Associate Professor, Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Claudia Costín, Professor and founding director, Center for Excellence and Innovation of Education Policies (FGV-CEIPE); CEO, Instituto Singularidades, São Paulo, Brazil. Former Senior Director for Global Education, The World Bank

Gunilla Dahlberg, Professor Emerita of Education, Department of Child and Youth Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden

Carmen Dalli, Professor of Early Childhood Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Angela Diaz, Dean of Global Health, Social Justice, and Human Rights, Jean C. and James W. Crystal Professor, Departments of Pediatrics, Global Health and Health Systems Design and Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, United States

Jaap E. Doek, Former Chairperson of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2001-2007); Leiden University Law School, Department of Children’s Rights, The Netherlands

Hasina Banu Ebrahim, UNESCO Co-chair for Early Childhood Education, Care and Development, University of South Africa, South Africa

Elvis Fokala, Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Tali Gal, Chair in Child and Youth Rights, Professor of Law and Criminology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Savitri Goonesekere, Emeritus Professor of Law University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

Jeffrey Goldhagen, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Florida College of Medicine, United States; President, International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health

Sally Holland, Athro Gwaith Cymdeithasol / Professor of Social Work, Ysgol Gwyddorau Cymdeithasol Caerdydd / Cardiff School of Social Sciences;

Children’s Commissioner for Wales (2015-2022), United Kingdom

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Fahmy and Donna Attallah Chair in Humanistic Psychology; Director, USC Center for Affective Neuroscience, Development, Learning and Education (candle.usc.edu); Professor of Education, Psychology & Neuroscience, University of Southern California, United States

Shin-ichi Ishikawa, Professor, Faculty of Psychology, Doshisha University, Japan

Philip D. Jaffé, Professor, Center for Children’s Rights Studies, University of Geneva, Switzerland; Member, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

Victor P. Karunan, Visiting Professor, Social Policy and Development, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand

Ondrej Kascak, Professor of Education and Head of Department, University of Trnava, Slovakia

Olga Khazova, former member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013-2021)

Ursula Kilkelly, Professor, School of Law, University College Cork, Ireland

Lothar Krappmann, Professor Doctor, Senior Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany (retired); former Member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2003 - 2011)

Mercedes Mayol Lassalle, Professor of Education, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina; World President, Organisation Mondiale pour l’Éducation Préscolaire (OMEP)

Yanghee Lee, Professor Emeritus, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea; Former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar; Former Chairperson of UN Committee on the Rights of the Child; President of International Child Rights Center; Founding Member of Special Advisory Council for Myanmar

Manfred Liebel, Professor Doctor, University of Applied Sciences Potsdam; Master Childhood Studies and Children’s Rights (MACR), Germany

Ton Liefaard, Professor of Children’s Rights, UNICEF Chair in Children’s Rights, Leiden University, The Netherlands

Laura Lundy, Professor of Children’s Rights, Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom; Professor of Law, University College Cork, Ireland

Kofi Marfo, Professor and Founding Director of the Institute for Human Development at Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya

Helen May, Professor Emerita of Education, University of Otago, New Zealand

Benyam Dawit Mezmur, Professor of Law, University of the Western Cape, South Africa; Member, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

Linda Mitchell, Professor of Education, University of Waikato, New Zealand

Zoe Moody, Professor, University of Teacher Education Valais & Center for Children's Rights Studies, University of Geneva, Switzerland

Peter Moss, Emeritus Professor of Early Childhood Provision, Institute of Education, University College London, United Kingdom

Vernor Muñoz, Head of Policy & Advocacy, Global Campaign for Education, Costa Rica; Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education

Endeley Margaret Nalova, Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Education, University of Buea, Cameroon

Elin Eriksen Ødegaard, Professor of Early Childhood Education, Director of KINDknow Research Centre, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway

Conor O'Mahony, Professor, University College Cork School of Law, Ireland

Ann Quennerstedt, Professor of Education, School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro University, Sweden

Sylvie Rayna, Professor Emerita; Senior Research Fellow, Centre de Recherche Interuniversitaire Expérience Ressources Culturelles Éducation (EXPERICE), Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, France

Elin Kirsti Lie Reikerås, Professor in Early Childhood Education, Leader of FILIORUM – Centre for Research in Early Childhood Education and Care, The University of Stavanger, Norway

Axel Rivas, Professor and Dean, School of Education; Director, Center for Applied Research in Education (CIAESA), Universidad de San Andrés, Argentina

Nevena Vuckovic Sahovic, Professor of International Public Law and Rights of the Child, Child Rights Centre, Belgrade, Serbia

Iram Siraj, Professor of Child Development and Education, University of Oxford, United Kingdom; Distinguished Research Professor University of Maynooth, Ireland

Mariana Souto-Manning, President and Irving and Neison Harris President’s Chair, The Erikson Institute Graduate School in Child Development, United States

Helen Stalford, Professor of Law, School of Law and Social Justice, University of Liverpool, UK

Beth Swadener, Professor Emerita, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University, US

David B. Thronson, Alan S. Zekelman Professor of International Human Rights Law, Michigan State University College of Law, United States

Kay Tisdall, Professor of Childhood Policy, University of Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom

John Tobin, Francine V McNiff Chair in International Human Rights Law, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne, Australia

Afua Twum-Danso Imoh, Associate Professor in Global Childhoods and Welfare, University of Bristol, United Kingdom

Michel Vandenbroeck, Professor of Family Pedagogy, Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy, Ghent University, Belgium

Wouter Vandenhole, Full Professor of Human and Children’s Rights, Law and Development Research Group, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Emily Vargas-Barón, Director, Institute for Reconstruction and International Security through Education (RISE), Washington, DC, United States

Philip Veerman, CPsychol, Health Psychologist, Youth Intervention Team, The Hague, The Netherlands

Ana Vergara del Solar, Professor, School of Psychology, Universidad de Santiago, Chile

Joanna Williams, Senior Director of Research, Search Institute, United States

Nicolás Espejo Yaksic, Centre for Constitutional Studies, Supreme Court of Mexico, Mexico

Kazuhiro Yoshida, Professor/Director, Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education (CICE), IDEC Institute, Hiroshima University, Japan

Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Courtney Sale Ross University Professor of Globalization and Education, Department of Applied Psychology, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University, United States

Note: Affiliations are listed for identification purposes only.

Global Citizens:

Open Letter to World Leaders

244 million children are out of school.

That’s more than the entire population of Brazil that is being denied the chance to learn. Children from families living in poverty are least likely to get an education, with many simply unable to afford school fees.

How can we build the world we want, beat the climate crisis, and achieve justice -- when 4 in 10 children don’t even finish secondary school?

We can’t.

Which is why we’re writing to you – as Nobel Peace Prize winners, former and current UN Special Rapporteurs, child rights experts, NGOs, education activists, and citizens from across the globe, with ONE BIG IDEA:

Let’s create a new global treaty that protects children and youth’s right to free education -- from pre-primary through secondary school.

We know this can work. After WWII governments were required to provide free primary education -- and now over 87% of children complete primary school. Today, we need to do something just as transformative and ensure we get ALL kids in school.

This isn’t just a lifeline for children. It’s a lifeline for us all. Educating girls is one of the most effective solutions we have to combating climate change.

So, let’s take it. Expand the right to free education now!

With hope and determination,

Malala Yousafzai, Pakistani education activist and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

Vanessa Nakate, Ugandan climate justice activist and founder of the Rise Up Climate Movement

and 535,000 other global citizens

Letter initiated by Avaaz, August 2022

CHILDREN:

Letter to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

June 2024

Excellency,

We are the Child Advisory Team from Child Rights Connect and we address this letter as a request for free, accessible, and good quality education at the pre-primary and secondary level for children around the world. Education is not only a fundamental right but also a means to realize other children’s rights; therefore, it is essential that every child benefits from it.

We are concerned that millions of children are denied access to education due to financial barriers. It is unfair that education, essential for a child's development and future aspirations, is often treated as a luxury that many children must forgo. Pre-primary and secondary education should be universally available and free for all children, regardless of their social and economic background. Urgent action needs to be taken for change to happen.

During our early years, we acquire skills that will serve us for life; we build socio-emotional bonds. As secondary school students, we know how education is equally crucial for skill development, preparing us for higher education and future employment. It equips us with the ability to become mindful global citizens with leadership skills, capable of thriving in a progressing and demanding society. Universal access to pre-primary and secondary education will promote equality and create a more just world for all children.

Utopia can be more than a dream: we want all children to have at least one year of free education before primary school and free education throughout secondary school. Let's stop dreaming and start building it.

All governments worldwide should support the development of international law to include these rights, with children expressing their views and adults listening—a collaboration that would generate a positive and inclusive change. This new international law is crucial to achieving educational justice and enabling us, children, to access the education we deserve. It will encourage international organizations, such as the UN, to develop accompanying measures as well as states to implement it at the national level, leading to policy and legal reforms.

Let's work together to ensure every child has the opportunity to receive quality, free pre-primary and secondary education. Education is the tool we need to bring about the change we want to see in the world. A country that prioritizes education is a country that progresses and chooses to invest in humanity. We hope that this call to action will mark the beginning of a positive transformation that will benefit the future of our children and our communities.

Sincerely,

Catarina, Dulce, Espoir, Freja, Hala, Lalit, and Throstur

Child Advisors within Child Rights Connect

CIVIL SOCIETY:

Letter to UN Member States

June 11, 2024

Permanent Representatives to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva

Re: Resolution to strengthen children’s right to free education

Excellencies,

We write as 22 non-governmental organizations to ask your government to support a critical initiative to strengthen children’s right to free education under international law.Specifically, we seek your support for a UN Human Rights Council (HRC) resolution, expected to be presented by Luxembourg, Sierra Leone, and the Dominican Republic at the upcoming 56th session, to establish an open-ended Working Group to draft an optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child that would explicitly recognize all children’s right to early childhood education and care; right to free public pre-primary education, beginning with at least one year; and right to free public secondary education for all children.

Education is not only a fundamental right for all children, but also one of the best investments that societies can make. It has the power to transform lives, lift individuals out of poverty, and foster social and economic development. The right to education is a multiplier of other rights, empowering girls and enabling individuals to participate in society. Children from disadvantaged and excluded groups are in greatest need of access to education and stand to benefit most. Yet for millions of children around the world, the cost of schooling remains one of the most significant barriers to education, particularly at the pre-primary and secondary level.

Through the Sustainable Development Goals and the related Incheon Framework for Action, all states have committed to make at least one year of pre-primary education free and compulsory, and all secondary education free, by 2030. Many countries have already made significant progress in guaranteeing access to free education. Currently, approximately 107 countries have enshrined at least one year of free pre-primary education in their domestic legislation, showcasing their recognition of the importance of early childhood education. Additionally, at least 117 countries guarantee 11 or more years of free primary and secondary education.

Yet the right to education as defined in international human rights treaties does not reflect these commitments and is no longer sufficient to ensure that children thrive in today’s world. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), for example, guarantees children free and compulsory primary education, but says nothing about early childhood education and does not oblige states to guarantee every child free secondary education.

We note increasing momentum for stronger international law on the right to education, including:

- A joint statement by 73 countries at the 53rd regular session of the HRC, expressing support for “efforts to strengthen the right to education, including the explicit right to full, free secondary education and at least one year of free pre-primary education.”

- An open letter led by Malala Yousafzai and Vanessa Nakate in advance of the 2022 Transforming Education Summit, signed by more than 500,000 people globally, calling on world leaders to support a new global treaty on the right to free education;

- A recommendation from the then-Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education, Koumba Boly Barry, for new binding international law to enshrine the right to pre-primary education;

- The Tashkent Declaration and Commitment to Action, calling for an exploration of a new legal instrument on early childhood education;

- Support from leading academics and international expertsfor a new optional protocol to the CRC to explicitly guarantee the right to free secondary education and at least one year of free pre-primary education.

It will be critical that the resolution ensures the meaningful participation of children in the drafting process of the proposed new optional protocol, something we hope we can count on you to actively support. Such consultation would bring meaning to the Convention on the Rights of the Child’s assurances that children freely express their views in all matters affecting the child, and their views be given due weight.

We firmly believe that more explicit international law on the right to free education can accelerate global progress and help millions of children access their right to education. We look forward to your government’s support and would of course welcome an opportunity to discuss the initiative and related issues with you in more depth.

Please accept, Excellencies, the assurance of our highest consideration.

Sincerely,

ActionAid

Association Internationale des Charités (AIC)

ATD Fourth World

Avaaz

BPW International

Childhood Education International

Early Childhood Research Centre, Dublin City University

Education International

Girls Not Brides

Global Campaign for Education

Human Rights Watch

Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER)

The Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion

International Office of Catholic Education (OEIC)

KidsRights

Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE)

Make Mothers Matter

Malala Fund

Plan International

World Organization for Early Childhood Education (OMEP)

World Vision International

Zonta International

MEMBER STATES:

Joint Statement on Children’s Education

53rd Session of the Human Rights Council (June 2023)

Item 3: Interactive Dialogue with the Special Rapporteur on the right to education

Mr. President,

I have the honour to deliver this statement on behalf of the Dominican Republic, Luxembourg, and a group of 70 other countries.

Everyone has the right to education: it is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which we commemorate the 75th anniversary, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and other core human rights instruments. Regrettably, worldwide, 244 million children and young persons are not getting an education for social, economic and cultural reasons.[58]

The cost of education remains a significant barrier, disproportionately affecting children and adolescents from low-income families, girls, children with disabilities and school-age persons in vulnerable situations.

Conflicts and the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated the global education crisis.

Furthermore, 4 out of 10 children and young persons do not complete secondary school and nearly half of all children of the world are not enrolled in pre-primary education.[59] A vast majority of countries have not achieved gender parity in secondary education.[60]

Education is a human right and plays a crucial role in the fight against inequality and for the consolidation of sustainable development. Today, we call on all Member States to guarantee access to free, quality, and inclusive education for all children from pre-school through secondary school, and ensure its adequate funding.

We support efforts to strengthen the right to education, including the explicit right to full free secondary and at least one year of free pre-primary education.

Thank you.

Alphabetical list of cosponsors:

1. Albania

2. Andorra

3. Argentina

4. Armenia

5. Australia

6. Austria

7. Azerbaijan

8. Bahamas

9. Belgium

10. Benin

11. Bolivia

12. Brazil

13. Bulgaria

14. Chile

15. Colombia

16. Costa Rica

17. Croatia

18. Cyprus

19. Czech Republic

20. Denmark

21. Dominican Republic

22. Estonia

23. Finland

24. France

25. Gambia

26. Georgia

27. Germany

28. Greece

29. Guatemala

30. Hungary

31. Ireland

32. Israël

33. Italy

34. Kazakhstan

35. Kyrgyzstan

36. Latvia

37. Lebanon

38. Liechtenstein

39. Lithuania

40. Luxembourg

41. Madagascar

42. Malaysia

43. Malta

44. Marshall Islands

45. Moldova

46. Monaco

47. Mongolia

48. Montenegro

49. Nepal

50. Netherlands

51. North Macedonia

52. Panama

53. Paraguay

54. Peru

55. Poland

56. Portugal

57. Qatar

58. Republic of Congo

59. Republic of Korea

60. Romania

61. San Marino

62. Serbia

63. Sierra Leone

64. Slovakia

65. Slovenia

66. Spain

67. State of Palestine

68. Sweden

69. Thailand

70. Timor Leste

71. Türkiye

72. Uruguay

73. Zambia

Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/RES/56/5

Adopted 10 July 2024

Open-ended intergovernmental working group on an optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the rights to early childhood education, free pre-primary education and free secondary education

The Human Rights Council,

Guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations,

Reaffirming the human right of everyone to education, which is enshrined in, inter alia, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Convention against Discrimination in Education of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and referenced in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other relevant international instruments,

Recalling the Human Rights Council resolutions on the right to education, the most recent of which is resolution 53/7 of 12 July 2023,

Welcoming the near-universal ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, in which States parties agreed, with a view to achieving the right of the child to education progressively, and on the basis of equal opportunity, to make primary education compulsory and available free to all, encourage the development of different forms of secondary education, including general and vocational education, make them available and accessible to every child and take appropriate measures, such as the introduction of free education and offering financial assistance in case of need, and noting the consistent work of the Committee on the Rights of the Child in examining the progress made in achieving the realization of the obligations undertaken under the Convention on the Rights of the Child by States parties thereto,

Reaffirming the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals contained therein, in particular Sustainable Development Goal 4, which is aimed at ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education, including early childhood, GE.24-12789 (E) A/HRC/RES/56/5 primary, secondary and tertiary education and technical and vocational training, with targets to ensure, by 2030, that all children complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes and that all children have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education,

Expressing deep concern that a significant number of countries have made only slow progress in raising early childhood education participation and secondary education completion rates, in particular with regard to children from low-income families and in marginalized or vulnerable situations,

Recognizing that the right to education is a multiplier right that supports the empowerment of all women and girls to realize their human rights, including the rights to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, to participate in the conduct of public affairs, as well as in economic, social and cultural life, and to fully, equally and meaningfully participate in the decision-making processes that shape society, and the transformative potential of education for every girl,

Expressing profound concern that, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 250 million children, adolescents and young people do not attend school, predominately at the secondary school level, that, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund, nearly 50 per cent of pre-primary age children around the world – at least 175 million – are not enrolled in pre-primary education, that costs to students or their families, social inequality and lack of infrastructure at the pre-primary and secondary levels remain important obstacles to access to education in many countries, and that girls are still more likely to remain excluded from education,

Noting that special procedure mandate holders of the Human Rights Council and treaty bodies have highlighted that providing free education includes removing not only fees but also indirect costs, including the cost of books, school materials, uniforms, transportation, examination fees, utilities and security, parent-teacher association fees, the payment of volunteering teachers, boarding school costs when parents have no other choice and, increasingly, the costs of digital devices and Internet connections, as well as providing free lunches, in particular for those unable to pay,

Taking note of the Youth Declaration on Transforming Education, in which young people demanded that decision makers eradicate all legal, financial and systemic barriers preventing all learners from gaining access to and fully participating in education,

Affirming the need to ensure equal access to educational opportunities and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices,

Welcoming the steps taken at all levels, including by low- and middle-income countries, to prioritize and allocate adequate resources, despite economic and financial challenges, to make pre-primary and secondary education free and accessible for all children,

Recognizing the long-term benefits of education, including on digital skills and literacy, in promoting economic growth, development, social stability and individual empowerment, and urging States to explore the innovative financial mechanisms, international partnerships and effective policy measures to ensure that every child receives a quality education without financial barriers, especially children in marginalized or vulnerable situations,

Urging the international community, including development partners, international financial institutions and non-governmental organizations, to support and cooperate with States in their efforts to provide quality, inclusive and free public education, including through non-conditional financial assistance, capacity-building initiatives and the sharing of best practices to help States to overcome economic constraints and successfully implement free education programmes, thereby helping to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all,

Taking note of the Tashkent Declaration and Commitments to Action for Transforming Early Childhood Care and Education, adopted at the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education, held from 14 to 16 November 2022 in Tashkent, in which participants outlined principles and strategies for inclusive, equitable early childhood care and education and, in emphasizing special reference to the most disadvantaged children, encouraged that the right to at least one year of free and compulsory pre-primary quality education for all children must be reflected in policies and legal frameworks, in which States committed to ensure further improvements and the implementation of policy and legal frameworks to guarantee the right of every child to inclusive, quality care and pre-primary education and in which the international community, non-governmental stakeholders and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization committed to examine the feasibility of supporting and enshrining the right to early childhood care and education in a legal instrument;

1. Decides to establish an open-ended intergovernmental working group of the Human Rights Council with the mandate of exploring the possibility of, elaborating and submitting to the Human Rights Council a draft optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child with the aim to:

(a) Explicitly recognize that the right to education includes early childhood care and education;

(b) Explicitly state that, with a view to achieving the right to education, States shall:

(ii) Make public pre-primary education available free to all, beginning with at least one year;

(ii) Make public secondary education available free to all;

(c) Recall that States shall promote and encourage international cooperation in matters relating to education;

(d) Consider a provision that would allow for States parties to the Convention on the Rights of the Child to incorporate all reporting on their obligations under the optional protocol into their reports submitted under article 44 of the Convention, eliminating the need for an initial or other separate reports;

2. Also decides that the working group will meet for five working days in Geneva in a hybrid format, including a webcast, and that its first session should be held before the end of 2025;

3. Further decides that the sessions of the working group will be dedicated to conducting constructive deliberations on a future optional protocol in accordance with the scope defined in paragraph 1 above;

4. Requests the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to provide the working group with all the assistance necessary for the effective fulfilment of its mandate;

5. Requests the working group to ensure the meaningful participation of children, in an ethical, safe and inclusive manner, and in particular to give children the opportunity to express their views on the topic and substance of the proposed optional protocol, to facilitate their expression, including through child-friendly information, to listen to children’s views and to act upon them, as appropriate;

6. Requests the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to ensure appropriate resources to support the participation of children, from all five regional groups, ensuring that they have easy access to relevant premises, and to make the discussions fully accessible to children and to persons with disabilities;

7. Decides to invite representatives of the Committee on the Rights of the Child to attend sessions of the working group as resource persons, as well as, where appropriate, relevant special procedures of the Human Rights Council and other relevant independent experts, and invites them to submit input to the working group for its consideration;

8. Invites States, civil society and all relevant stakeholders, including through consultations with parents, legal guardians and educators, to contribute actively and constructively to the work of the working group;

9. Requests the working group to submit a report on progress made to the Human Rights Council for its consideration no later than at its sixty-second session and to make the report available in an accessible and child-friendly format.

34th meeting 10 July 2024

[Adopted without a vote.]

Co-sponsors: Albania, Armenia, Bahamas, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burundi, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Finland, France, Gambia, Germany, Georgia, Ghana, Honduras, Hungary, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malawi, Malta, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Monaco, Nauru, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Republic of Moldova, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Spain, Ukraine, Uruguay, Uzbekistan

[1] UNESCO, Global Education Monitoring Report 2024, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391406, p. 155.; UNESCO Institute of Statistics, https://sdg4-data.uis.unesco.org/.

[2] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Education Monitoring Report 2024. Leadership in Education: Lead for Learning (Paris: UNESCO, 2024), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391406 (accessed November 5, 2024), p. 155.

[3] Ibid.

[4] UNESCO Institute of Statistics, https://sdg4-data.uis.unesco.org/ (accessed November 6, 2024). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000390215/PDF/390215eng.pdf.multi (accessed October 18, 2024), p. 23.

[5] UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), A World Ready to Learn: Prioritizing Quality Early Childhood Education (New York: UNICEF, 2019), https://www.unicef.org/media/57926/file/A-world-ready-to-learn-advocacy-brief-2019.pdf (accessed January 11, 2024), p. 4.

[6] UNESCO, Global Education Monitoring Report Summary, 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All (Paris: UNESCO, 2020), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373721 (accessed January 11, 2024), p. 27.

[7] See, e.g., Wael Moussa and Carina Omoeva, “The Role of Secondary Education Tuition Fees in Enrollment Behavior in Malawi,” Education Policy and Data Center, 2016, https://www.epdc.org/sites/default/files/documents/Omoeva_Moussa_manuscript.pdf (accessed January 11, 2023); Chengfang Liu et al., “Development Challenges, Tuition Barriers, and High School Education in China,” Asia Pacific Journal of Education, vol. 29, no. 4 (2009): 503-20, accessed January 11, 2024, doi:10.1080/02188790903312698; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (“CRC Committee”), General Comment No. 11, Indigenous children and their rights under the Convention, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/11 (2009), art. 59; CRC Committee, General Comment No. 20, Implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence, UN Doc. CRC/C/GC/20 (2016), art. 71; UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education, “The Promotion of Equality of Opportunity in Education,” UN Doc. A/HRC/17/29 (2011), arts. 56-58.

[8] Alison Earle, Natalia Milovantseva, and Jody Heymann, “Is Free Pre-Primary Education Associated with Increased Primary School Completion? A Global Study,” International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, vol. 12, no. 13 (2018): accessed January 11, 2024, doi:10.1186/s40723-018-0054-1; UNESCO, SDG 4 Scorecard: Progress Report on National Benchmarks: Focus on Early Childhood (Paris: UNESCO, 2023), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384295 (accessed January 11, 2024), p. 28; Natalia Milovantseva, Alison Earle, and Jody Heymann, “Monitoring Progress Toward Meeting the United Nations SDG on Pre-primary Education: An Important Step Towards More Equitable and Sustainable Economies,” International Organisations Research Journal, vol. 13, no. 4 (2018): 146, accessed January 11, 2024, doi:10.17323/1996-7845-2018-04-06.

[9] UNESCO, Global Education Monitoring Report, 2023. Technology in education: a tool on whose terms? (Paris: UNESCO, 2023), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723 (accessed October 7, 2024), p. 231.