For the past nine months, Human Rights Watch has continued to document ongoing atrocity crimes and human rights violations in Palestine and Israel. On July 17, we published a report on the events of October 7, 2023, “‘I Can’t Erase All the Blood from My Mind’: Palestinian Armed Groups’ October 7 Assault on Israel.”

For this report, we analyzed over 280 videos and photographs that, combined with witness accounts, helped to identify exactly what happened on October 7, where and when and to whom, as well as who was responsible. The purpose of this research was to bring facts to light and support accountability efforts by documenting the abuses committed on October 7 and identifying those responsible.

We documented 12 breaches of the physical barrier separating the Gaza Strip and southern Israel and 29 civilian sites, including 19 kibbutzim, five other cooperative communities, the cities of Sderot and Ofakim, two music festivals and a beach party, which at least five Palestinian armed groups attacked. Our research showed that the early morning breaches of the barrier required considerable planning and coordination.

Documenting which groups took part, identified through headbands associated with specific armed groups and online activity belonging to specific armed groups where footage was posted with captions claiming responsibility, was key to identifying those responsible for leading and coordinating the attacks.

Establishing the day’s timeline was an essential aspect of our research. It is this “when?” that we focus on in this methodological deep dive. Below we take one case as an example to explain the various methods we use to identify time.

This case is a video that stood out in our research. It was posted online on November 8, 2023, to an anonymously run Telegram channel established on October 9 by self-described Israeli first responders called “First South Responders.” The nearly nine-minute video is distressing because it depicts fighters torturing and ill-treating an individual they had captured and whom they may have taken hostage. It shows at least 20 men on motorbikes and on foot on a road in southern Israel wearing a mix of olive-green camouflage and what appear to be Israeli military uniforms or uniforms resembling those worn by the Israeli military. We documented other instances of fighters wearing uniforms that resembled the uniforms worn by Israeli military on October 7, which is a laws-of-war violation when worn during attacks. Some were also wearing the distinctive green headbands of the Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas. This armed group is the largest and most active in Gaza and led the October 7 assault.

The footage shows the group coming across a man dressed in civilian clothing who was hiding inside a roadside bomb shelter. The armed men beat him and restrain him with zip ties. Several factors indicate that the video was filmed very early in the day and therefore could help us identify which group was involved in carrying out the initial breach into Israel.

We needed to work out exactly where and when the video was filmed. The caption in the video said it was filmed on Route 232, a road that passes through the so-called “Gaza Envelope” – the areas of southern Israel surrounding the Gaza Strip – near many of the kibbutzim attacked on October 7.

The video shows long shadows cast by the men on motorbikes. A few seconds into the footage, the sun appears low in the sky, indicating it was either sunrise or sunset, and from interviews of events that day, we deduced it was most likely sunrise.

We set out to confirm the video was filmed in Israel, which attack sites it would have been near, and to gain an indication of the direction in which the fighters were traveling. We also needed to know the exact location to establish the time it was recorded.

Finding the Where to Know the When

We knew the video was recorded on a main road based on the road’s size and markings. As the video plays, some road signs come into view, and then a bus stop with a shelter next to it.

To find the location of a video, in a process called geolocation, we usually compare the images in a video with satellite imagery of the area. In many of the places we work, this is often the only available reference material we have. However, in some contexts, such as Ecuador, Ukraine, and the United States, street imagery is also available through large tech companies like Google, Yandex, Baidu, and in the case of Israel, Apple. Being able to use such imagery to follow the journey the Qassam Brigade fighters took in this video proved helpful to establish the direction they were coming from and where they were headed.

While the caption in the video said that they were traveling on Route 232, looking more closely at the road signs showed the number 242 above them. Examining and verifying the where, when, and what of each piece of content and not taking any information at face value is an essential part of our work.

We traced the Route 242 from Gaza towards Israel and quickly found on Apple Maps’ “Look Around” feature the same road signs, bus stop, and shelter we saw in the video just 750 meters south of Kibbutz Kissufim, a kibbutz 2.3 kilometers from the border with the Gaza Strip that came under attack on October 7 and where at least 13 people were killed and four others were taken hostage.

Without such useful clues as the road sign and the data from street imagery, we could have used other landmarks to identify the exact location on satellite imagery, such as the telecommunication towers in the background, the junction the motorcycles pass, and the bus stop next to the shelter.

With all street imagery, it is important to check the date it was taken, as there may be differences in the video with the street imagery depending on when the image was captured. With some street imagery tools like Google and Yandex you can view historic imagery. This allows a viewer to compare imagery over time and further narrow down the dates on which incidents may have taken place. Other tools, like Apple Maps, just provide the month and year the most recent imagery was taken. To view the date of the imagery in Apple Maps, we selected the full screen option in “Look Around” and then clicked on the three dots icon, on Imagery. That showed it was last updated in February 2021. Since it was recorded over two years ago, some structures shown in the video may have changed, so we double checked the video on more recent satellite imagery to confirm the location.

Now that we had the exact location, we could start looking at the shadows in the video. By understanding their length and direction, we could estimate the time the video was filmed.

Analyzing Shadows with a Digital Sundial

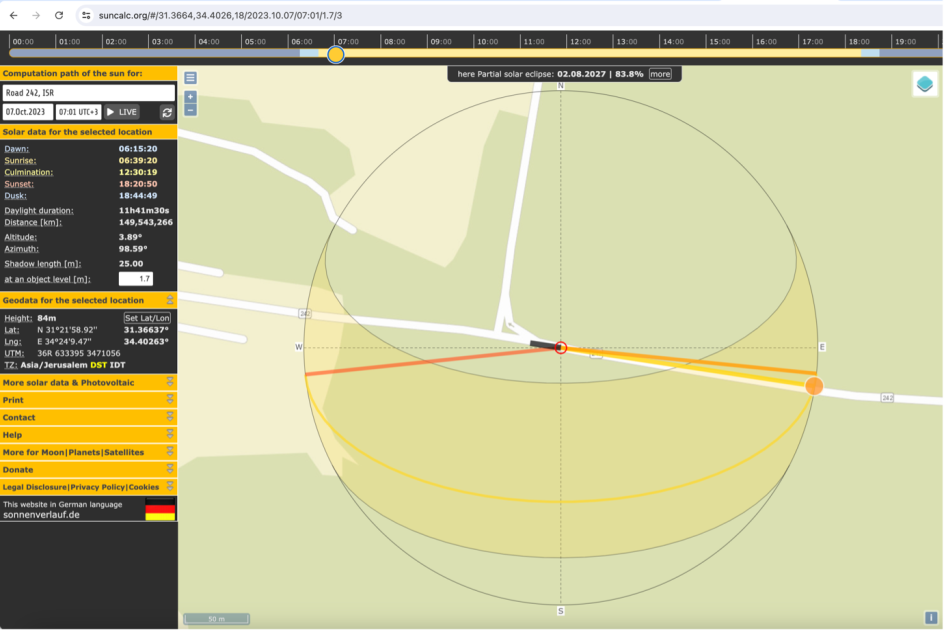

To do this, we used a free tool called SunCalc. Like many open-source tools, SunCalc was not created with the intention of assisting human rights investigators. However, it has become an important part of our toolkit. By entering the location in coordinates, the date and estimation of the height in meters of the object casting the shadow, you can see how long a shadow is and in which position it is being cast. We chose to enter in the height of the men standing in the road as the objects and used the average height of an adult man, 1.7 meters tall.

By clicking on the blue icon on the right of the screen, you can select satellite imagery as the basemap. This allows you to line up the location more accurately, as the international investigation group Bellingcat points out in a helpful tutorial.

We changed the time bar on the top of the tool to match the direction of the shadows we saw in the image. This led us to conclude the video was taken around 7 a.m. It is important to put this into the context of that day – we knew from our interviews with survivors that the assault began at roughly 6:30 a.m. with a barrage of rocket attacks towards Israel followed by the breaches. Another functionality of the SunCalc tool helped us pinpoint when sunrise, dusk, and sunset was in these locations on October 7.

Understanding the time through shadows was an invaluable method for this research. We used it for most videos we verified to corroborate witness accounts and check the time stamps present on CCTV and dashcam footage.

Tick Tock – Looking for “Ground Truth”

After isolating the time and location where the video was filmed, we then analyzed the content, including any evidence of abuses. In the video, the armed men stopped 750 meters south of Kibbutz Kissufim. There, they came across a man hiding inside a roadside bomb shelter or megunit with his car nearby.

The fighters beat him, took his valuables, and stole his car, leaving him lying on the road with his hands and feet zip-tied together. We noticed a flash from a watch face during the assault – something we always look out for as it can provide a more accurate time and can act as another data point to check against other methods for identifying the time.

Watches, clocks, or phone displays are also helpful to understand the time when videos are filmed inside or in the dark where shadows are no longer helpful. In the open-source analysis conducted for the report, along with shadows, we heavily relied on time stamps from CCTV cameras and vehicle dashcams, but we were also able to read three watch faces and one wall clock, which often gave us a reliable “ground truth” of the time.

We had to always be cautious with this data, however, as clocks, watches, and time stamps might be incorrectly set or not updated when daylight savings time changes. We had one example of this, where a CCTV camera with the time stamp of 6:44 a.m. captured footage of fighters entering a house in Sderot. In the footage, a wall clock hanging on the outside wall showed the time as an hour later at around 7:45 a.m. One of them was wrong, so we went back to interviewees and asked them follow-up questions about the time when fighters entered their house and looked at the shadows in the videos, which both confirmed to us that the wall clock was incorrectly set. In another instance, the time stamp of a CCTV camera filming Kibbutz Be’eri displayed 5:55 a.m., however the video was filmed at dawn based on the light in the video and, after referencing when sunrise was on October 7 with SunCalc, we knew it would have been shot at least at 6:45 a.m.

We turned back to the flash of a watch we saw on video outside Kissufim. The person filming the video takes a banner from the backpack of another fighter wearing a Qassam Brigades headband. As he does this, the flash of his digital watch is visible showing the time 7:14. We ascertained this by going frame by frame in the video, making sure we caught every small movement.

In the video, the man takes the green banner with the logo and slogan of the Qassam Brigades and wraps it around the car of the man lying on the road. This video was important to provide more information about the identity of the groups responsible for the attacks.

As part of our research into the attacks, Human Rights Watch spoke with Yeela, a resident of Kissufim, who said she awoke to a siren at 6.30 a.m. She said she heard gunfire and explosions for an hour after the siren rang as she hid in her home’s safe room. With this time in mind, our time analysis fitted with this account that fighters would have been nearby at around 7 a.m.

Inspecting Social Media Time Stamps

Next it was time to find out more about how this video came to be filmed and posted online to try to establish who filmed it, who posted it, and when. Establishing these elements helps with checking the authenticity of the video and its contents. It was posted on an anonymous group’s Telegram channel on November 8, 2023. As this was over a month after the attacks, the precise time it was posted – 3:43 p.m. – was not particularly relevant. However, in other cases, the time posted can be crucial to the research, for example, when determining when the first time a video was posted or establishing when armed groups took the first hostages to Gaza. In the case of Shani Louk, a hostage who was killed, there was a video of her body transported by truck in northern Gaza posted on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) on October 7. Knowing what time the video was first posted, especially if it was posted in real time or close to real time, could help us to better understand the timeline of events.

Various social media platforms and messaging applications time-stamp their content differently. As a general rule, Facebook, Telegram, and X show users the time a post was uploaded converted into the time zone of their computer (Facebook and TikTok are set to UTC as a default). Identifying the time therefore requires assessing in which time zone the person uploading the content’s computer was likely to be set. For instance, this video was uploaded at 15:43:53 on November 8, 2023, according to the time stamp of a Human Rights Watch computer set to CET.

We don’t know who runs the South First Responders Telegram channel or what time zones their computers are set to, but they have said online they are Israeli first responders, so we assessed that the most likely time zone in which the video was posted was Israel Standard Time (IST). Using a date and time conversion website, we determined that the likely time of upload was 4:43 p.m. IST.

In general, due to the fact that we cannot be absolutely certain in what time zone a post was uploaded, if we include information about time stamps from social media, we typically include the caveat, “according to the time stamp,” to account for some margin of error, and we always include as much other corroborating information as possible.

Metadata Matters

When the video was downloaded, we checked the metadata through a tool called ExifTool and saw that it seemed to have been modified in QuickTime, a media player with some editing functions, on November 8, 2023, at 10:23 a.m. (according to the uploader’s computer) before being posted hours later.

Metadata – data about data – in this case about a video, photograph, or audio – is helpful to understand the provenance of and changes made to a file. Most social media and messaging platforms strip metadata, making any checks ineffective. Telegram, like WhatsApp, and Signal, lets users upload files as documents and retain the original metadata.

This might be useful, for instance, if we had metadata telling us that the video was created before October 7, 2023. This would have raised questions about the authenticity of the video. In other cases, file names might give away interesting pieces of information as to the file’s provenance. Metadata itself can easily be manipulated, but it is a good first step to understanding the provenance of a file.

According to the Telegram account that posted the video, the video itself was recovered from a device on the body of a fighter who had apparently filmed the footage. The fighter was most likely wearing a GoPro-type camera on his head due to the angle at which it was filmed and the curved edge emblematic of a wide-angle lens. We spotted a glimpse of the fighter’s reflection in the car he later drove. In it, a camera is visible, attached to his forehead.

Time Again

These geolocation and chronolocation processes are the same we use in much of our research at Human Rights Watch to work out if, where, and when a human rights violation, war crime, or otherwise notable incident occurs. We look at videos and photographs to analyze light, shadows, devices showing the time, metadata, and the time they were posted online. We couple this open-source work with on-the-ground or remote interviews with witnesses, survivors, and other sources, asking them date and time-related questions to verify and add context to our research.

For the October 7 research, we interviewed 94 survivors of the attack and another 50 people, including family members of survivors, hostages, and those killed; first responders who collected human remains from the attack sites; medical experts who examined the human remains and provided forensic advice to the Israeli authorities; officials from the municipalities affected by the attacks; and journalists who visited the attack sites after the areas had been secured by the Israeli armed forces.

Understanding the time, location, and activities in this key October 7 video led us to important conclusions about the Qassam Brigade’s involvement in the assault in southern Israel that day. It also provided an example, among others we documented, of torture and ill-treatment of a civilian by the fighters. Through our research we found that the Qassam Brigades led the attack on October 7 and carried out 10 of the 12 breaches of the physical barrier separating Gaza and Israel.

We applied this same methodology described to all the audiovisual content, including the hundreds of videos and photographs we analyzed and verified in the report. To aid in the reader’s understanding of how we know what we know, we added footnotes that describe the time-telling techniques we used in each video.

To read more about our methodologies employed when combining witness accounts and visual analysis, read how we combined methodologies to investigate 46 attacks in Idlib, Syria; how we verified videos in Israel and Palestine in the initial days after the October 7 attacks; how we remotely investigated Russia’s devastation of Mariupol, Ukraine; or how we combined 3D spatial reconstruction techniques with video verification and geospatial analysis to investigate apparent war crimes on the Tajikistan/ Kyrgyzstan border.

Visual information can tell a lot, if you know what to look for and how to analyze it. At Human Rights Watch, we continue to explore new technical and information-gathering methods to analyze and verify visual content.