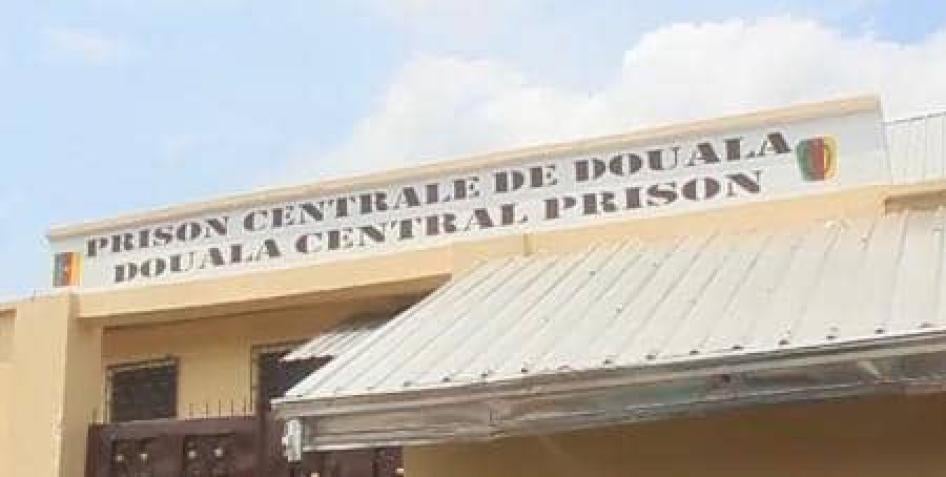

At least six inmates in Cameroon’s second largest jail, the “New Bell” prison in Douala, have died since March from the country’s cholera outbreak. A bacterial disease that causes severe diarrhea and dehydration, cholera is usually spread in water and can be fatal if not quickly treated. The latest victim, 30-year-old political prisoner Rodrigue Ndagueho Koufet, died on April 7.

According to Cameroon’s health minister, 105 people have died in the outbreak since October. The disease has so far been identified in 6 out of the country’s 10 regions, including the troubled South-West, where the health system has been severely affected by the violent crisis between government forces and armed separatists groups.

Koufet was among the over 500 people arrested during opposition-led demonstrations across Cameroon in September 2020 that were violently repressed by security forces. According to lawyers for the opposition party Cameroon Renaissance Movement (Mouvement pour la renaissance du Cameroun, MRC), at least four other MRC supporters have been diagnosed with cholera at “New Bell.”

There are fears the death toll could rise substantially in the overcrowded facility which currently houses about 4,700 prisoners, 4 times its capacity – most of whom are in pretrial detention, in violation of international norms. “We are 50 squeezed in a 9 square meters cell. There’s no drinking water, and the hygienic conditions are deplorable,” a man held in the same cell as Koufet told Human Rights Watch.

The government took measures to curb the spread of cholera, such as rolling out a vaccination campaign, encouraging regular hand washing, and ensuring drinking water is potable. But in Cameroon’s overcrowded prisons, even the most basic hygienic measures are hard to practice.

This cholera outbreak shows how quickly abysmal prison conditions become life-threatening. Cameroon has an obligation under international law to ensure all detainees are held in humane and dignified conditions and to guarantee their right to health. It also should not be detaining people in pretrial detention except in exceptional circumstances. Authorities should release those at increased risk of severe complications from cholera, including children and older people. Prisons should also address overcrowding by releasing those held for minor offenses, those nearing the end of their sentence, and many of those being held in pretrial detention, or people like Koufet, who were detained for peacefully exercising their rights. Authorities should also ensure access to clean water and sanitation for prisoners.

The government should act quickly not only to prevent the disease from spreading, but to protect those who depend on them for protection.