What were your first impressions of the impact of this conflict on civilians?

The conflict in the Tigray region has taken place in a virtual blackout. A lengthy communications shutdown, and the closure of road and air access, has meant only a trickle of information has come out. Parties to the conflict have largely controlled the information and narratives.

So before setting off for the region, we were unsure what we would uncover. We travelled by road from Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, to the eastern al-Gadaref state, bordering Ethiopia, which hosts more than a third of the more than 52,000 Ethiopian refugees who have fled to Sudan since the fighting started in November. Most of our interviews were in the remote, arid, and sprawling Um Raquba camp.

We found a population still in shock and scared, caught completely off guard by the sudden nature of the violence they experienced. While people spoke of tensions building in recent months between the federal and regional governments, few expected the outbreak of hostilities that would force them to flee their homes.

We heard stories of lives turned upside down. We spoke to mothers who said they had been sitting in their homes baking injera, the traditional Ethiopian flatbread, when they had to flee without their children after heavy bombardments near their homes. We spoke to a young man who was bathing in the river when he witnessed shelling commence on his city, and with many farmers who returned home from a day’s work in the fields only to find their homes empty and villages deserted.

Refugees from western Tigray said that when fighting broke out, many fled by foot first to neighboring towns and farmlands in western and central Tigray, only to encounter more fighting. With phone and internet communications cut off, people were forced to rely on word of mouth and rumors to make snap, life-or-death decisions.

Many families were separated in the rush to flee the violence. The pain of separation and lack of news about the fate of relatives clearly weighed on the people we spoke to. Parents and spouses would break into tears when describing efforts to find their loved ones. A 70-year-old man recounted how he carried his wife’s clothes with him as he fled to Sudan, searching for her on the way and hoping they would be reunited. Five weeks on, he still had no news of her whereabouts.

What abuses did you uncover?

Residents of towns in western Tigray – the area bordering Sudan that was affected by heavy fighting in the conflict’s first weeks – recounted similar stories. They described initial heavy shelling, notably in the town of Humera, which borders Eritrea and Sudan, or gunfire before federal government forces entered a town. These troops would be followed by paramilitary police forces known as “Liyu Hail” from the neighboring Amhara region and young members of Amhara youth militia groups known as “Fano.”

Some residents described being caught in the crossfire between federal government and allied and TPLF forces in the farmland on the outskirts of towns as they attempted to flee or hide.

Witnesses described significant civilian deaths during the initial offensives and fighting. Medical professionals, notably in Humera, described being overwhelmed by the influx of injured civilians and bodies of those who had been killed in the heavy shelling.

The shelling and gunfire in several towns forced many civilians to first cower inside their homes, and then run for their lives toward neighboring towns or the countryside, leaving elderly relatives behind, as well as possessions and recent harvests. Many reported seeing dead bodies along the way as they fled.

A number of refugees said that they witnessed extrajudicial executions by federal forces and their allies during the fighting or after they took over towns. Witnesses said that some of the victims were suspected TPLF members, fighters, or supporters and retired soldiers. However, businesspeople and farmers were also targeted, as were others whom the soldiers happened to have stopped, including families and children trying to flee. In the town of Mai-Kadra, a number of refugees reported seeing hundreds of dead bodies which had been shot, stabbed, or hacked with knives, machetes, and axes, including those of ethnic Amharas but also of Tigrayans. Family members from several towns said they saw loved ones killed but could not offer them a proper and dignified burial.

People who remained in their homes or went back to their towns after the heavy fighting had subsided said they saw Amhara “special forces” and Fanos, as well as unidentified gunmen, detain those who remained, and loot abandoned and inhabited homes, shops, and hospitals. People said gold, animals, recently harvested produce, as well as goods from electronics shops were stolen. Many expressed concerns and fears about what they may face if they returned home.

What stories, images have stayed with you?

While many of the stories we heard were heart-wrenching, one in particular stands out. A young man, a minibus driver, told us about seeing a friend’s two young children, aged 6 and 10, lying dead on the streets in the town of Shire. They had been killed during what he described as heavy shelling of the town. The same young man broke down at the end of our interview as he described how two of his friends whom he had escaped with were shot dead by Amhara Liyu Hail when they were within reach of the Sudanese border.

What can the refugees expect in Sudan?

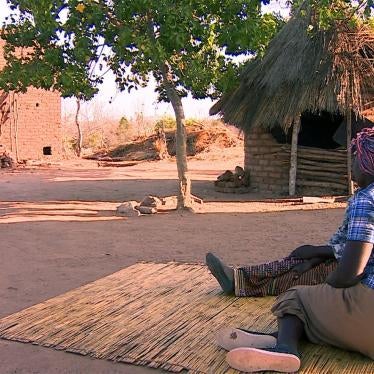

Leaving the Um Raquba camp each evening was harrowing: there was a long line of old buses parked just outside the gates of the refugee camp in the pitch dark, full of newly arrived refugees, with bewildered looks on their faces. What awaits them in the camps is stark: the communication network is very poor, which adds to the anguish of people desperately trying to find news about their loved ones and their homes. Only a handful of the people we interviewed had been able to reconnect with relatives since arriving in Sudan; even after communications were restored in western Tigray, most were still awaiting news. The camp is also kilometers away from the nearest town.

We spoke to several elderly Ethiopian refugees who had spent their youth as refugees in Sudan’s Um Raquba camp during conflict and famine in Ethiopia in the 1980s, who now risk spending the last years of their lives destitute in the same remote camp.

Many Ethiopians we spoke to said they feel safe, at least for the time being, in Sudan, but the future looks bleak. Some of those who fled initially stayed close to the border, hoping to be reunited with family or to be able to return and check on homes, property, and livestock. But many are now being relocated to the Um Raquba camp.

Many refugees had to flee the fighting with nothing but their basic possessions, often only the clothes they were wearing at the time. This was compounded by the fact that the banks had been closed in the Tigray region since early November, leaving many short of cash even before fleeing. Others had to pay security forces manning checkpoints in order to pass, or had money and phones confiscated while still in Ethiopia. Assistance currently available to support the influx of refugees is still in the early response phase but appeared basic: we saw new arrivals unsure of where to go, long lines of people including many children, queuing up at midday under the sun to get food, overstretched health facilities, and people without shelter. Several refugees expressed frustration by the lack of information they had received since arriving in the camp as to what services they were entitled to and could expect.

What is Human Rights Watch calling for?

Most urgently, there needs to be unhindered access for humanitarian assistance to the many civilians who are still displaced or stranded within the Tigray region, including in areas that the government considers unsafe. Civilians seeking protection and a safe haven should be allowed to flee, both within Ethiopia and into neighboring countries.

Given the gravity of allegations of abuses by all parties to the conflict, as well as the failure of the Ethiopian federal government to follow through on past commitments to investigate abuses during unrest, international involvement in investigations into events in the Tigray region is key. The Ethiopian government should allow the United Nations high commissioner for human rights to send a fact-finding team of investigators into the region to document the conduct of all parties, to ensure that evidence of abuses is preserved, and help determine the full impact of this conflict on civilians. This is particularly important given the various security forces and armed groups involved.

The violence and horror experienced by civilians in the Tigray region over the last seven weeks, adds to the wounds felt by many communities across Ethiopia affected by cycles of violence over the last two years. It highlights the urgent need for the authorities at all levels to work to build trust among communities, to ensure that the rights of all are respected without discrimination, and that those responsible for abuses are fairly and appropriately punished.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.