Summary

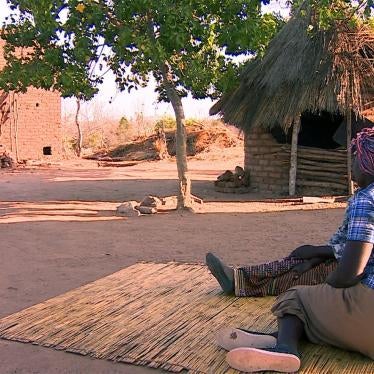

When Michelle, 57, was widowed in 2012, she lost more than her husband. Shortly after his death, her in-laws took over the fields she had tilled for decades. They also stole the fruit from the trees in her kitchen garden and sold the harvest, leaving her without any livelihood. They further harassed, intimidated, and insulted her by surrounding and physically restraining her and telling her to leave her home, in an attempt to chase her away.

Michelle’s neighbors advised her to contact Legal Resources Foundation, a legal aid organization that could help her protect her inheritance. It was only after this organization took the matter to court and Michelle obtained restraining orders against her in-laws that she was able to go back to tilling her fields. But her in-laws continue to threaten to take her only cow, so she still worries about the future: “I am fearful and my heart is unsettled.”

Glynnis, 50, was not as fortunate as Michelle. When her husband of 20 years passed away, her in-laws made it clear that they no longer wanted her around:

After his death, things became difficult. There was no support for food, and I couldn’t send my children to school. They [my in-laws] kept saying I should leave the house.… They kept saying to go away, which pained me, so I left. I just left my marital home.

They also took five cattle and household items. I tried to get [my husband’s army pension] but [his relatives] wouldn’t sign the paperwork. I have gotten nothing. I believe that this is unfair to my children … [but] I have given up. I can do nothing [to stop it].

Glynnis left the home she had owned with her husband, seeing no way to keep her property in the face of constant harassment from her in-laws. She went to the house where she grew up, which is now owned by her brother. Her brother agreed to let her and her three children farm some of his land, and she now farms and pays government taxes—a levy for all farmers—on the land. Glynnis no longer owns a property.

Based on interviews with 59 widows in all 10 provinces of Zimbabwe between May and October 2016, this report documents the human rights vulnerabilities and abuses that widows in Zimbabwe face. Around the world, millions of older women—and older people generally—routinely experience violations of their human rights. This report focuses on abuses related to property grabbing from widows, predominantly older women.

Chronological age is not the exclusive determinant of whether a person will experience old age discrimination. A widow who is perceived as being older because of physical and other attributes, such as white hair or wrinkles, could face age discrimination regardless of her calendar age. Most of the widows we interviewed could have been perceived as older and may have been targeted for property grabbing because of relatives’ real or imagined belief that they would be unable to defend themselves. Violations against older people are common and include discrimination, social and political exclusion, abuses in nursing facilities, neglect in humanitarian settings, and denial and rationing of health care. Most abuse goes undocumented and the perpetrators unpunished, as governments, UN agencies, and human rights actors have long ignored the rights of older people.

The abuses documented in this report were experienced by older and younger widows. Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives of nongovernmental organizations and legal aid organizations who provide support to widows and conducted an extensive review of relevant domestic legislation and policy documents.

According to the 2012 census, Zimbabwe is home to around 587,000 widows, and most women aged 60 and over are widowed. Many of these older women are vulnerable to violations of their property and inheritance rights. Every year, in-laws evict thousands of widows from their homes and land, leaving them with no roof over their head, no means of income, and no support networks. Others face persistent harassment from in-laws who often accuse them of being responsible for the death of their husbands.

More than 250 million widows around the world face multiple abuses, neglect, and social exclusion and too frequently are pushed into extreme poverty; the Loomba Foundation estimated that in 2015, 38,261,345 million widows were living in extreme poverty. For some, the abuses they face as widows continue a lifetime of gender-based discrimination abuse and deprivation that often includes being married as a child, being deprived of education opportunities, abusive marriages, and other violence. The effects of discrimination based on gender and other statuses accumulate across the life course. When confronted with yet another status upon which they might be discriminated—their marital status of widowhood—older widows face even more heightened vulnerability.

Despite these abuses, the rights and needs of widows are not mentioned in some of the most important policy-setting documents on women, poverty, and development. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action did not mention widows, nor did the Millennium Development Goals, or their replacements, the Sustainable Development Goals. Important development donors, such as the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), do not reference widows in their gender policies, as is the case with the World Health Organization’s Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health. The United States Agency for International Development, another development donor, merely references widows’ property rights in its gender policy, and the 2002 UN Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing notes widows’ risk of poverty and widowhood rites. These are scant references when compared to the scope of challenges widows face.

Zimbabwean law provides for relatively equal property and inheritance rights for men and women. However, many of the women Human Rights Watch interviewed struggled to claim those rights for reasons unique to their status as widows. In Zimbabwe’s recent history, men traditionally owned all family property, and when women were widowed, they were often “inherited” as wives by male relatives of their deceased spouse. In Zimbabwe today, wife inheritance is no longer the norm and property can be held by both men and women. However, few women formally own the property held in their marriage. As a result, their ability to keep the property they shared with their husband upon the death of their husband becomes dependent both on proving their marriage, which can pose great challenges, and on warding off in-laws intent on property grabbing.

There are three types of marriage in Zimbabwe: the civil marriage (monogamous, registered marriage recognized by the state, commonly referred to as a “5.11 Marriage”), the customary law marriage (under which a man may have more than one wife but is registered), and the most common, the unregistered customary union. These unregistered customary marriages are not registered officially with any government agency or local officials. Without any official record of the marriage, a widow who wants to make a claim to property that was held in the marriage but is formally owned by the late husband (or members of his family) has to demonstrate that she was indeed married to him. Doing so is tricky because the courts can require confirmation from the widow’s in-laws, who are the very people who stand to benefit if the marriage is not confirmed. Not surprisingly, many of the widows Human Rights Watch interviewed said their in-laws were unwilling to provide such confirmation.

No fewer than two thirds of the women who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they experienced the profound injustice of their in-laws taking over their homes or property, and feeling helpless to stop it. Others simply did not know that they had property and inheritance rights to begin with and were unable to withstand the intimidation tactics used by their in-laws such as daily shaming, harassment, and physical assaults. Others said that they were wary of jeopardizing relationships with in-laws with whom they had shared their lives for many years, and whom they had hoped would support them and their children in familial and cultural ways.

Widows who decided to mount legal fights to keep their property told Human Rights Watch that they faced major barriers doing so. They described an array of procedural and practical hurdles. They said that they had to travel long distances to reach government agencies and courts; that correspondence about claims was often sent to family members of their late husbands, who had little interest in sharing it with them; and that court fees were prohibitive. Being stripped of their only means of income (the United Nations estimates that over 70 percent of women are involved in the agricultural economy in Zimbabwe), these widows also faced a catch-22 situation: they needed proceeds from their property to pay the cost of proceedings, and they needed to pay for the proceedings in order to get back their property. Almost all of the women we interviewed who successfully reclaimed their property were assisted by nongovernmental organizations. Without this legal support, the barriers appear insurmountable for most widows.

Widows also face strong social pressure to accept property-grabbing by in-laws, some of which, families assert, derives from interpretations of customary laws. Some families assert that under customary laws for their communities, only those “in” the family, i.e., men, are entitled to inherit land and property. Others say that within this customary system, widows will be protected and provided for by the male in-laws who inherit. But too often in the modern context, there is no such protection. While customary laws can evolve and change and can offer opportunities to advance women’s equality, they can also be interpreted or applied in ways that discriminate against women, especially widows. The government of Zimbabwe should promote customs and practices that favor women’s equal rights to land and other assets, including through inheritance, and engage traditional leaders in discussions about interpretations of customary laws that recognize equality of men and women.

The African Union adopted a new Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Older Persons in Africa in January 2016. The protocol, which is now open for ratification, creates new legally binding standards for the rights of older people. Article 4 of the Protocol on the Rights of Older Persons requires that states parties “ensure the provision of legal assistance to Older Persons in order to protect their rights.” The protocol calls for states parties to “put in place legislation and other measures that guarantee protection of older women against abuses related to property and land rights; and adopt appropriate legislation to protect the right of inheritance of older women.” It also states that “all necessary measures should be taken to eliminate harmful traditional practices affecting older persons.” Through this protocol, the African Union recognizes the importance of older people’s enjoyment of human rights on an equal basis with others.

Under other international human rights law, countries are required to ensure equal rights for men and women, including equal property and inheritance rights for widows and widowers. Zimbabwe has ratified the regional and international human rights treaties that require the government to eliminate discrimination against women and to guarantee their rights to justice, non-discrimination, equality in marriage, physical security, and property. This includes the African Union’s Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol).

Zimbabwe has taken some important steps to create a legal framework that protects women’s property and inheritance rights, but further reforms are needed. The 2013 constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex and gender and states that all persons are equal before the law. The Marriage Act and the Customary Marriages Act require registration of marriages for those marriages that are solemnized according to either act. But the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that at least 70 percent of women living in rural areas are in unregistered customary unions and are living under customary law. Those acts do not apply to these marriages, so people in these marriages currently have no applicable formal legal regime for protection.

Several laws on succession of estates and on maintenance of a deceased person’s family in Zimbabwe appear to provide for equal inheritance rights from spouses for women and men. However, they are out of reach for those many widows who cannot prove that they were married through a marriage registration. They further provide that maintenance payments from the estates are to be administered according to the rules that apply in case of divorce, which excludes property that was acquired by inheritance, custom, or is of “particular sentimental value.” Since men (not women) have typically inherited land and other valuable assets, in practice there are few assets that widows can inherit.

The government of Zimbabwe should do more to bring its laws into line with the constitution, in keeping with the African Union and international human rights frameworks, to protect the rights of all married people regardless of their type of marriage, providing critical protection for older women who are, or may become, widows. While this report focuses on Zimbabwe, violations of the rights of widows are a significant problem in many countries around the world. The international community and individual governments have an obligation to end abuses against widows around the world.

Key Recommendations

To the Government and Parliament of Zimbabwe

- Amend all relevant laws and regulations to bring them in line with the 2013 constitution.

- Introduce a system that ensures all existing and new marriages, including customary unions, are officially registered.

- Allow the posthumous recognition of marriages and customary unions with witnesses to confirm the marriage of the widow’s choosing.

- Engage in public awareness campaigns to end unlawful property grabbing and inform widows of their inheritance rights.

- Ensure widows, including those in rural communities, have meaningful access to legal remedies to protect their rights to property and other related rights in cases of unlawful property or inheritance grabbing.

Methodology

Older women who are widows face two kinds of discrimination that made this report so pressing: they experience discrimination based on gender across their lives, which accumulates in old age, and they face intersecting discrimination based on their age, gender and marital status as widows. Their identities cannot be reduced to one or another of these traits. Rights in widowhood face unique threats because of this convergence.

Human Rights Watch considered a number of factors when choosing Zimbabwe as the location for this report. Abuses against widows in the country have been documented, and local NGO partners and advocates were welcoming of an opportunity to work on the issue. The new constitution’s prohibition against laws that discriminate against women—even customary laws—and efforts to align national laws with that new constitution was a determining factor. The time is right for Zimbabwe to take stock of the insidious harm of property grabbing and a lack of access to justice is causing widows and their families around the country.

This report is based on research conducted between April 2016 and October 2016, including visits to Zimbabwe. Field research was conducted in the capital, Harare, in Bulawayo, Gweru, and two small towns, with widows traveling to speak with us from towns and villages across each of Zimbabwe’s 10 provinces. Throughout this report, a pseudonym is used in place of the name of each widow to protect her privacy.

During these research visits and remotely, Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with more than 85 different individuals, including 59 widows, 5 government officials, and 23 representatives of nongovernmental organizations. Human Rights Watch met with Nyasha Chikwinya, the minister of women’s affairs, gender and community development, to discuss the findings of this research. The minister promised to carefully review the report and its recommendations. Human Rights Watch also interviewed the master of the high courts, a local mayor’s office, and a member of parliament. We wrote to the minister of justice (see Annex 1), but had not received a response at time of writing.

While this report focuses primarily on the abuses older widows face, Human Rights Watch interviewed widows of a range of ages. 29 of the 59 widows Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report were 50 years of age or older.

While old age is frequently defined by chronological age—for example the official retirement age—it is generally not biological age that determines whether or not a person is perceived and treated as an older person or is exposed to the risks or vulnerabilities commonly associated with old age. Thus, analyses incorporate whether a person was subjected to old age discrimination regardless of calendar age and whether a person suffered human rights violations related to the aging process, such as frailty, chronic disease, or disability.

Most interviews were conducted in private, in the offices of partner NGOs. Many widows traveled to urban locations of partner NGOs from their homes in rural areas. For most interviews, a Human Rights Watch researcher (a native speaker of Shona) translated from Shona into English. For some interviews, a staff member from a partner NGO translated from Shona or Ndebele into English.

Interviews were conducted by asking similar open-ended questions to each person and covered a range of topics related to property and inheritance rights of widows. Before each interview, we informed interviewees of its purpose, informed them of the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific questions without consequence and that their names would remain confidential. Human Rights Watch did not offer any financial or other reward to the people who agreed to be interviewed for this report.

We identified widows through legal aid providers and grassroots widows’ NGOs in rural areas. As such, we could not reach many widows who are socially and geographically isolated. Such widows may not have access to services provided by legal aid organizations and may be worse off than many of the women we interviewed.

All documents cited in this report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

Key Terms

|

Access to Justice |

A basic human right that refers to ensuring an individual’s access to courts, including traditional courts and/or legal representation so that legal and judicial outcomes are just and equitable. |

|

Ageism |

A form of discrimination or stereotyping against people on the basis of their real or perceived older age. According to HelpAge International, a leading older persons’ network, “[a]geism results in prejudicial and stigmatising attitudes and behaviour that belittle, patronise and exclude us in our older age, deny us autonomy and dignity, and create barriers to enjoyment of our human rights on an equal basis with others in every aspect of life.” |

|

Customary law |

Common practice that is unwritten, accepted, expected, and required conduct that coexist alongside formal laws. In Zimbabwe, customary laws are legal practices recognized by the state as binding law. |

|

Customary law marriage |

A marriage created through traditional common practices but solemnized at the Magistrate’s Court in Zimbabwe, and it permits the husband to have more than one wife. |

|

Lobola |

A practice whereby a bridegroom’s family makes a negotiated bride price payment to the bride’s family, often in the form of cattle and/or cash. |

|

Marriage registration |

A document that shows that a marriage is recognized by an entity such as a government or the local traditional leadership. |

|

Widow |

A woman whose husband has died. |

I. Background

The Rights of Older People

Older people are the fastest growing population group in the world. Abuses against older people are common, including discrimination, social and political exclusion, abuses in nursing facilities, neglect in humanitarian settings, and denial and rationing of health care. Most abuse goes undocumented and the perpetrators unpunished, as governments, UN agencies, and human rights actors have long ignored the rights of older people.

Human Rights Watch is developing a new body of work to document the different kinds of human rights violations older people face; to advocate for better protections of their rights at the national and international level; and to identify potential gaps in human rights standards. This work will focus both on the effects of old age discrimination, or ageism, on people perceived to be older and human rights violations related to the aging process, such as frailty, chronic disease, or disability.

For the first report in this series, we focused on the rights of widows; older women make up a significant majority of older people in the world and widows are often particularly vulnerable to human rights abuses. We chose Zimbabwe for this research because property grabbing from widows remains a serious problem, yet the new constitution provides real opportunities for progress and civil society groups are actively working to end the practice. Violations of the rights of widows are a significant problem in many countries around the world, and we call for a concerted effort to address the rights of widows, and older people generally, throughout the world.

The Invisibility of Widows in Global Policy and Development

As of 2015, an estimated 258 million women globally are widows.[1] Most are older women. In sub-Saharan Africa, over 55 percent of widows are over the age of 60.[2] The Loomba Foundation, a grant-making and research organization that promotes the welfare and economic empowerment of disadvantaged widows, finds in its 2015 Global Widows Report that almost 15 percent of widows worldwide “live in extreme poverty where basic needs go unmet.”[3] Widows often face discrimination based on a combination of their gender, age, and marital status.[4]

Specifically, they face vulnerabilities based on perceptions of old age, social isolation, and stigma. Widows face varying challenges in different countries and cultural settings. In parts of Asia, widows often face harmful practices of social exclusion, segregation, and social isolation.[5]

In Africa, the Loomba Foundation notes that “[f]orced eviction from the family home and seizure of even the most meagre of cooking utensils by the late husband’s family are widespread.”[6] In a number of communities in sub-Saharan Africa, they may face rape or coercive sex as a “cleansing” ritual after their husband’s death, along with other harmful practices, such as wife inheritance.[7]

Property grabbing can be common in the region of Southern Africa.[8] The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN has described the eviction of widows and orphans from their homes in Zimbabwe as “widespread.”[9] The Stop Violence Against Women Project offers guidance for legislation to combat property grabbing.[10] The International Justice Mission, an international NGO working to prevent violence against people living in poverty, works to protect widows from property grabbing in Uganda and Zambia.[11] And in 2015, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women decided that that the Tanzanian government should compensate two widows who brought complaints before the committee for property grabbing and called for constitutional and customary law reforms, as well as practical measures to eliminate this type discrimination in Tanzania.[12]

Globally, many widows face extreme poverty due to a lack of access to pensions or other social protection measures. Global AgeWatch, a publication by HelpAge International, notes that in low- and middle-income countries, just one in four people over 65 receives a pension.[13] For older widows, informal labor and breaks in formal employment to care for others over their lifetimes can further reduce contributory pension prospects in countries with such options available.

Discrimination, social exclusion, and abuse against widows violates international human rights standards, and over the past decade, a number of NGOs have begun to draw attention to these abuses. Widows for Peace Through Democracy, a global umbrella NGO for widows’ associations and NGOs, has created a Widows Charter “to inform and influence law reform and the drafting of new constitutions in the post-conflict transition period.”[14] The Global Fund for Widows, another NGO, provides skills training, job services, and micro-finance to fight poverty among widows in Egypt and Bolivia.[15] And the Loomba Foundation produces the world’s most complete collection of global statistics on widows in its reports. Long predating these global initiatives, small groups of widows in countries around the world have banded together to help each other, and faith-based communities often provide some services or supports for widows.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which has been a cornerstone of work on equality and empowerment for women and girls for two decades, does not mention widows. Nor do the Millennium Development Goals or the Sustainable Development Goals, despite the risk of poverty widows face. The World Health Organization’s Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health also does not mention widows. Important development donors, such as the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), do not mention widows in their gender policies. The United States Agency for International Development, another development donor, does reference widows’ property rights in its gender policy, and the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing note widows’ risk of poverty and widowhood rites. These are scant references compared to the scope of the challenges widows face.

Harmful Practices and Widows in Zimbabwe

Widowhood is common in Zimbabwe. According to the 2012 census, 14 percent of women in Zimbabwe are widows.[16] That census found that over 587,000 women are widows, and many of these women are old or will become old.[17] In terms of chronological age, the percentage of women who are widows increases drastically at older and older ages. In Zimbabwe, 37.8 percent of women aged 55 to 59 are widows, and 78.3 percent of women aged 75 and over are widows.[18] Women who are widowed at a younger age are likely to carry that stigma with them for decades. The life expectancy for a woman who is 60 years of age in Zimbabwe is over 78 years.[19]

Widows have traditionally had a socially weak and therefore vulnerable position in Zimbabwe, made all the more vulnerable by old age and discriminatory practices in customary law and government procedures. Women and Law in Southern Africa produced a position paper together with the property and inheritance rights network of Zimbabwe on suggested amendments of inheritance laws. It found that women who do not have marriage certificates face challenges in court. They may be required by the court to bring affidavits or testimony from their late husband’s relatives to confirm the marriage. Sometimes these relatives completely deny the existence of the union and state that the customary law wife was a “mere girlfriend.”[20]

These practices contribute to the vulnerability of widows. This may explain how opportunistic property grabbing remains such a common phenomenon, according to women’s rights advocates, and also according to Human Rights Watch’s research.

Some customary norms reinforce widows’ socially weak position, including certain aspects of customary laws on marriage and on inheritance. This is especially true in communities with patrilineal inheritance, which practice descent through males, as was the case with the communities where the widows Human Rights Watch met lived. While customary laws can evolve, and can offer opportunities to advance women’s equality, Human Rights Watch found that they are interpreted or applied in ways that disadvantage women, especially widows.

Proving a customary marriage is a serious burden and impediment for widows in the existing legal system. There is no clear moment when a customary marriage begins.[21] A wedding ceremony may not take place. In prevailing cultures in Zimbabwe, at the start of a marriage, the groom’s family negotiates a bride price, or lobola, to the bride’s family. Sometimes this agreement is written, which, if in the possession of the widow, can be used to help prove the marriage. The lobola often includes some combination of cattle and cash. In other contexts, the practice of lobola may give the impression to family members of the husband that they have already paid money to the bride (even though wives do not receive any of the lobola) and therefore widows should not be entitled to inheritance upon the death of a husband.[22]

In most communities in Zimbabwe, women have traditionally left their own families upon marriage and moved in with their husbands on property shared with or adjacent to their husband’s family. This property is considered to belong to the husband or his family, often not registered in the name of the husband or wife.[23] Even though customary marriages should be registered with the government according to the Customary Marriages Act of 1997, Human Rights Watch found many of these marriages are not registered, leaving a widow without a certificate as evidence of the marriage.[24] Despite her contribution to the land and property (over 70 percent of women who are employed in Zimbabwe are employed in the agricultural sector), not having a certificate is a disadvantage when attempting to claim inheritance rights.[25]

According to informed sources in Zimbabwe, until recently, it was common for a widow to be “inherited” by a male relative of her husband, along with the couple’s property. In many cases, this amounted to a forced marriage, as the widow would believe that she had no choice but to marry the relative under customary practice. This form of “wife inheritance” or “widow inheritance” served to keep land and other property within the deceased husband’s family and was meant to protect the widow and surviving children. Zimbabwe has grappled with high rates of HIV prevalence since the late 1980s.[26] As the epidemic has continued, the practice of wife inheritance has decreased.[27] While it is a positive development that widows are less often forced to marry an in-law, some in-laws still feel entitled to the property of the deceased, and property grabbing continues.

Another harmful practice that compounds the vulnerability of many widows is child marriage, which is common in Zimbabwe, with approximately one in three girls marrying before their 18th birthday.[28] Child marriage engenders life-long problems: many girls do not continue school; early pregnancies can strip them of opportunities and may lead to poor health throughout life; and they are at increased risk of violence within their marriage.[29] The payment of lobola may contribute to this persistent practice, as it motivates parents to marry off their daughters at an early age. Child marriage can make a woman who was married as a child even more vulnerable when she becomes a widow, including because child marriages are rarely registered. The Zimbabwe Constitutional Court ruled in 2016 that child marriage is unconstitutional, but the government has done little to end the practice.[30]

Finally, polygamy remains common in Zimbabwe, creating additional complications and risks for widows. A 2010-2011 demographic and health survey found that 7.1 percent of urban women and 13.4 percent of rural women between the ages of 15 and 49 years knew they were in polygynous marriages in Zimbabwe.[31] Not all women know that they are in polygynous marriages. Some widows are surprised to find that other potential wives make themselves known only upon the passing of a husband. This is a source of great uncertainty. With multiple widows competing against each other and their husband’s family for property, a larger and more complicated fight can commence for a smaller share of the property.

Zimbabwe’s Dual Legal System

Zimbabwe has a formal legal system that operates in parallel with customary law. Customary laws are generally unwritten but are recognized by Zimbabwe’s 2013 constitution, which defines them as “the customary law of any section or community of Zimbabwe's people.”[32] Zimbabwean legal expert Slyvia Chirawu of Women and Law in Southern Africa Research and Education Trust pointed out: “[N]orms, practices and traditions … ultimately crystalize into customary law.”[33]

Customary law is used extensively in Zimbabwe. The Customary Law and Local Courts Act details the circumstances under which customary law applies.[34] Customary law is a powerful cultural force. It is particularly potent with respect to marriage and inheritance matters for widows, but it impacts a lot of what goes on in the country. An estimated 80 percent of women in Zimbabwe “live in rural areas, marry under customary law, and do not register their marriages.”[35] Customary law may hold sway over these women’s lives much more than formal, national laws.

Zimbabwe officially requires the registration of two of the three types of marriages.[36] But as evidenced by the high percentages of unregistered customary unions (estimated at 70 to 80 percent of women’s marriages in rural areas, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN), this lack of a legal framework and avenue for registration leaves widows in a weak position when seeking to claim their rights in the civil law system.

Currently, the only avenue for obtaining posthumous recognition of a marriage that the legal system offers widows is verification by in-laws. In-laws, of course, stand to benefit from their son’s or brother’s marital property if they choose not to verify the marriage. This, combined with customs related to property and the history of wife inheritance, creates significant hurdles for widows seeking to assert their property rights. Section III discusses Zimbabwe’s laws on intestate succession and marital property.

According to Chirawu, "[c]ustomary law is a living phenomenon and it is imperative that any efforts to eradicate its harmful aspects go beyond the passage of general [civil] laws.”[37] Awareness raising around widows’ rights and enforcement of civil laws are also critical to changing customary law.

Developments in Neighboring Countries

Botswana and South Africa are neighboring countries that have taken formal steps to improve women’s property rights and inheritance laws. The progress shown in these countries represents a potential blueprint for Zimbabwe to improve the rights of widows.

In Botswana up until 2013, men and women had equal rights under civil law only with regard to decision-making on family property management, including upon death of a spouse. In customary or religious marriages, the eldest son assumed the role as head of the household.[38] In 2013, in the case of Mmusi and Others v Ramantele and Others, the Botswana High Court upheld the right of women to inherit property, “rejecting the tradition of males as sole heirs.”[39] That case specifically addressed inheritance by daughters on an equal basis with sons, rather than inheritance by widows, but the court’s decision referred more broadly to equal inheritance rights of women. It ruled that customary inheritance law in Botswana discriminated against women and was therefore unconstitutional.[40] The parallels to other countries in the region are clear. “This is a significant step forward for women's rights not only in Botswana but in the southern Africa region, where many countries are addressing similar discriminatory laws,” noted one regional advocate.[41]

South Africa also passed a Recognition of Customary Marriages Act in 2000.[42] This act made an important innovation: allowing marriages to be registered after the death of a spouse.[43] South Africa’s constitution allows for customary laws that do not conflict with the human rights guaranteed under its Bill of Rights.[44] In practice, the country still grapples with unregistered customary marriages and estate registrations.[45] Zimbabwean legal scholars have pointed out that while South Africa’s Recognition of Customary Marriages Act provides some positive avenues for change, the law stops short of providing for situations in which relatives are uncooperative in registering their marriage after a husband’s death, a major challenge for widows in Zimbabwe.[46]

South Africa’s courts have also ruled that certain customary laws on inheritance are unconstitutional where they discriminate on the basis of sex. For example, in the case of Bhe v Magistrate Khayelitsha, a Constitutional Court of South Africa case in 2004, property inheritance exclusively along male lineages was found to run counter to the constitution’s prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex.[47] This case was brought by a widow on behalf of her two minor daughters. Like the Mmusi case in Botswana, this case specifically addressed inheritance by daughters on an equal basis with sons, rather than inheritance by widows, but the court’s decision referred more broadly to equal inheritance rights of women.

One important impact of the Bhe v Magistrate Khayelitsha ruling was the creation of the Recognition of Customary Marriage Act. But researchers studying its impact in South Africa in March 2016 found:

The implementation of the Recognition of Customary Marriage Act and of intestate succession rules found that in most cases, when a family member died, the estate was administered outside the new rules, and the families did not follow the new rules when distributing the estates.[48]

The continued administration of estates outside the civil law—and continued discrimination against women in inheritance rights—shows that legal change alone is not enough to change some harmful practices without addressing the root causes of such opportunism, including a lack of legal empowerment, unequal power dynamics between genders and within families, and a lack of enforcement of formal law.

II. Findings: Property Grabbing from Widows

During our research, dozens of widows told Human Rights Watch that their in-laws grabbed their property after their husbands died. They described myriad ways in which this happened. Widows said their in-laws threatened, physically intimidated, and insulted them. Some were forced out of their homes immediately. Others had distant in-laws turn up years after their husbands’ deaths, demanding property. Still others had their livelihoods constricted as in-laws stole or commandeered their productive assets like fields, cattle and other livestock, and gardens. They told Human Rights Watch how in-laws forcibly evicted them; attempted to obtain title to their land and marital homes behind their backs; sold off their inventory from family shops; and diverted their income from rental properties. Widows also said that their in-laws had made the painful insinuation that the widows themselves might be responsible for the deaths of the husbands. Many widows told us how they lost everything.

Illustrative Cases of Property Grabbing from Widows

Many of the widows interviewed for this report said that they were surprised when their in-laws tried to take their belongings because they felt they had a good relationship with them during the marriage. Deborah, 58, from Mashonaland East, said her in-laws constantly harassed her to force her to leave after her husband died. She married at the age of 10 and spent four decades working the family land and contributing in many ways to the marital assets. Although she said that her husband had told her before he died that she should be able to stay in her house and continue to work their land, his brother had other ideas:

When my husband died in 2005, my brother-in-law said to go back to my family’s home…. I had been looking after the land and homes for decades. My brother-in-law told me: “I am not your father. You should not be here.” He has taken all of my fields and even tilled my yard [to plant crops] up to my doorstep. Now, he says that I cannot walk on “his” fields. He says that I do not belong there. I reported this to the village headman, but he just tells us to live in peace. My brother-in-law is insistent. Maybe he is really happy to see us suffer. At my age, where can I go? I cannot start afresh.[49]

Bethel, 41, lives near Bulawayo and said she was surprised at her brother-in-law’s attempts to take her property after her husband died in 2013:

Before my husband was even buried, my brother-in-law was making moves. He was running around from [government] office to [government] office. He tried to get my husband’s pension. They [officials] said it wasn’t ready but that he needed the death certificate for it. He got the death certificate by saying that his brother [my husband] was a widower … I learned about three weeks after my husband’s death that I was [being] left out. He took my car. I was surprised that this happened. We were a close family.[50]

Annabelle, 50, lives near Bulawayo and told Human Rights Watch that things were relatively quiet with her in-laws in 2013 when her husband passed away. It was a surprise when they began harassing her years later:

In January 2016, [my in-laws] came and fought with me. The police were called and said that the in-laws needed a court order to evict me. My in-laws wanted me to leave so that they could rent out my house. I raised the money to hire a lawyer. The lawyer helped. He advised me not to leave the house. I had to pay the lawyer US$300 in advance, and I sold a cabinet to do so.

My husband never got along with them. I wish the lawyer would do something to prevent the family from coming back. It worries me and I want to have peace.

Many widows said they wanted to seek peace with their in-laws and to preserve relationships, even after their in-laws had taken everything from them. Many did not fight back against in-laws’ attempts to take their property, hoping to prevent family discord. Thelma, 45, lives near Harare and was 32 when her husband passed away. She and her husband had written a will and had some means to hire a private lawyer, yet she still capitulated to some of her in-laws’ demands. She described how desperate she was to make peace:

The relationship was okay when we were married…. We used to visit them in rural areas often. We sent them money every month…. My husband told me [when he was dying] not to give even the small items like his clothes [to his family], but I wanted to. He said: “One day I will die, and I want to leave you as much as possible so that you can pay for school [for our son].”

At the memorial service, my in-laws [told me they] wanted everything. I went to the memorial service with the tombstone and his clothes for distribution. Six big suitcases. They said, ‘Why did you bring the tombstone and nothing else?’ They refused the clothes. They wanted a stove or a fridge. Later, I tried to give the clothes again, and my father-in-law took them. The will [which my husband had prepared] gave me a [Toyota] Hilux pickup truck. My father-in-law said that he wanted it. The lawyer said it was not for him. But I gave it to him, to try to stop problems.

By custom, if a child is sick, you are supposed to consult with the in-laws, but they never come. They won’t pay the children’s school fees. My in-laws are greedy. Whenever we meet, they say they want the house. You cannot feel free. They were threatening at first. I wanted to put my house in my son’s name, but I put it in my name, because I feared for his protection [his safety].[51]

Even with Thelma’s attempts to seek peace, her in-laws continue to pressure her. Master of the High Court Mr. Eldard Mutasa told Human Rights Watch, “Standing up and going to the police to report property grabbing takes guts. These widows are running the risk of being banished. People fear that risk.”[52]

Some widows told Human Rights Watch that they, and sometimes their late husbands, had anticipated efforts by in-laws to grab property and took steps to try to prevent it. Charity, 49, from Mashonaland East, told Human Rights Watch that she first watched her in-laws grab the property of her sister-in-law when her husband’s brother died.

At the funeral of my brother-in-law, a few years previous to my husband’s passing, they [my in-laws] took everything, and left my sister in-law and kids destitute. I took them in.

Now, my mother-in-law sleeps on her son’s [my brother-in-law’s] marital bed, with blankets made as gifts for him and his wife.[53]

She took that as a cautionary tale and sought help from her sister, who is lawyer, when her husband passed away. Charity’s sister met with the family, explained that she was a lawyer and that she would take them to court if they tried to grab the property. Charity said that her in-laws still grumble and she willingly materially supports her mother in-law, but they have not made a move to grab her property.

Registration of Marriages

Human Rights Watch found that the lack of registration of customary unions is one of the most significant enablers of the grabbing of property of widows in Zimbabwe. Widows without registered marriage certificates were easy targets for property grabbing because of the difficulties proving a marriage after a husband’s death. A leading women’s rights group in Zimbabwe, said of widows: “The most pressing issue is that of unregistered customary law unions that although recognized for purposes of inheritance, are not always easy to prove.”[54] Zimbabwe’s Master of the High Court, Mr. Eldard Mutasa told Human Rights Watch “I see these cases every day. People should always register their marriages. If it is not registered, she [the widow] will be at the mercy of the family. It is blackmail, and it is common.”[55]

Although both Zimbabwe’s civil laws and international law clearly require that all marriages be registered, most marriages in Zimbabwe are not. And Zimbabwe lacks a centralized or digitized register of marriages. This sets women up for property grabbing when they become widows. One expert observed that unregistered customary unions are “‘popular’ for a number of reasons. While many people do not know that they need to register their unions, those who do know may not realise the benefits of having their union registered. For others, it is logistically difficult to have their unions registered.”[56]

Many of the widows Human Rights Watch interviewed said their in-laws were unwilling to provide confirmation of marriages that had not been officially registered. Annabelle, 50, initially tried to defend her right to her home in court against her in-laws without a lawyer:

We owned our house, but only his name was on the title…. His relatives were saying that I should leave, but I didn’t. I went to court [to confirm the marriage and claim the house]. His relatives said that they didn’t know me in court. They court asked me for any papers I might have to show our marriage. I had lobola papers and his will that was read at the funeral that said that we were married. But the family made a fake will and took it to the court.[57]

It was then that Annabelle sought the assistance of a lawyer, who in the end secured her right to her home through the court.

Having a registered marriage helped some women to hold on to their property and, to some degree, prevented threats of property grabbing or the need to resort to the courts. Glenda, 72, married in 1963, and she and her husband registered their traditional marriage. After her husband passed away, she told Human Rights Watch: “They [my in-laws] respected me. No one went against my wishes. I had cattle in my own name, and I used them to send my children to school.”[58] She said the marriage certificate helped to discourage in-laws from grabbing (or attempting to grab) her property.

But even a marriage certificate was not always sufficient protection from property grabbing from widows. In some cases, in-laws even attempted to take over widows’ properties when the marriage was officially registered or a husband had a will that explicitly left property to his widow. Virginia, 64, lives around Harare and also had a marriage certificate. She said her husband’s younger brother was incensed when he found out they had registered their marriage:

He took many things, including his [my husband’s] suits. He wanted more, and tried to keep the death certificate from me. I went to him four times to ask for it. After the fifth time, I involved the police…. He insulted me when I went to see him for the certificate. “You need a death certificate because you want to sell the property,” he said. He said that it was in line with customs that I take steps to inform [my husband’s] relatives and obtain their consent for selling anything.[59]

Widowhood and Child Marriage

Child marriages are unlikely to be registered, putting widows who married as children at risk of property grabbing and difficulties claiming inheritance. For some, the deprivations of widowhood come on top of those of being married as a child. With high rates of child marriage in Zimbabwe, many widows are also former child brides. Michelle said she ended up marrying a man whose children were already her age: “[H]e gave gifts to the elders, said he wanted a wife. They left me no choice.”[60] Her marriage was unregistered, which left her with higher hurdles to protect her home and property after her husband passed away.

Women who married as children without the opportunity to go to school were less likely to have independence from their husbands during their marriages. When they become widows, they may have fewer resources or ability to pursue a remedy in the face of property grabbing. Gladys, 43, was married when she was 14 because she “was an orphan with no money for school.” Her husband was 45 years old at the time. He passed away at the age of 70. She told us how the son of her husband’s first wife tricked her out of her home. He picked her up for her husband’s funeral in a car, and after the funeral he told her that he would not bring her home because her home was now his. “Because I was in mourning, this confused me, and he was not providing any food. There was no will. Everything was distributed by the family ‘according to custom.’”[61]

Some widows said they married when they were children because their parents were poor. Zelda, 56, told Human Rights Watch she married when she was 16 and remembered how she was looking for a way out:

I saw the poverty of my family. My family worked as laborers and did farming. Life was very tough. We had no options. I just thought that if I could find a responsible man who would think of them, things would get better.[62]

Today, she sees the effects of that early poverty and her status as a widow. She told us: “People have taken advantage of me because I didn’t go to school and I am a widow with no husband to protect me.”[63]

The Impact of Property Grabbing on Widows’ Lives

Widows described the various ways in which property grabbing affected their lives. Many said it drove them into poverty; some said they became homeless; and others said their children dropped out of school because they could no longer pay school fees.[64]

Linda, 32, from Midlands, has a child with a disability who needs to attend a special school. Since her husband passed away five years ago, she has not been able to pay the school fees:

We had five cattle in our marriage, and my in-laws sold three of them without compensating me. I am struggling to keep up…. The worst part of it is that the relatives are not even concerned with the welfare of the child.

The family has refused to register the estate [to begin administering the inheritance]. I have requested that they help register the estate, but they say they will not write my name on my estate, only my son’s name…. It is painful that you have worked for something with your husband and then people come and want to grab it.[65]

Widows Human Rights Watch spoke with had little choice about which laws applied to them. Family members determined that customary inheritance practices would be followed, and widows could not change this. Marie, 80, was married from 1967 to 2010, when her husband passed away.

We did a traditional marriage, and a wedding, which was my husband’s idea…. He passed in October 2010. We lived in the same town where I was born and exchanged visits with my in-laws often during our marriage.

When he [my husband] passed, he had two sons [from another marriage]. I raised [the eldest son] from the time he was five years old, when his mother left us. He said he was taking the oxcart, fields, businesses, and all 30 cattle. “Go back to your parents’ house,” he said. I was 73. He became violent, threatening me. He harassed me in my home. After the funeral, my brothers-in-law were there, and he said in my face: “You are rubbish and you will get nothing. I am taking everything.” I was so pained by this. I had so much pain that I could not sleep.

My husband and I had built that business together. He [the son] was being greedy. A number of times, he chased me away from my home, and I would find safety with the police. The police said that he could not do that, and he would relent, then continue to chase me away and harass me.[66]

Mindy’s story is similar to Marie’s. The 54-year-old widow explained her experience to Human Rights Watch:

I didn’t see the will but found out that there was one in court. My brother-in-law was the executor [of my husband’s will]. He mistreated me. Immediately after [his death], I sold household effects to survive for food. My in-laws saw that I sold things to buy food. My brother-in-law had me arrested [for selling things in the estate]. In court I was found not guilty. I served one week in jail [before trial]. It was terrible. One week was like a month.[67]

Florence, a 62-year-old widow from Midlands whose husband passed away in 1998, told Human Rights Watch that her husband’s relatives moved in and grabbed her house and rental property. It was not until 2014 that she heard about Legal Resources Foundation through their village-to-village outreach, and she began working with them to get her property.

When a husband dies, his relatives go straight to the property. The kids don’t go to school; you can’t sustain yourself…. Since then, I’ve been struggling and haven’t been able to move on. I’ve been suffering … I look like a grandmother because I have been struggling. My sisters look much younger than me.[68]

Zimbabwe’s master of the high court says that such cases are common, and “there is no such culture that deprives people of primary things for life. Only the clothing qualifies for customary distribution.”[69] Property grabbing does not just harm widows, it also harms those in their care. Deborah spoke about the impact the harassment she faced from her brother-in-law after her husband’s death had on her children: “The constant harassment they experience means that tears are always on their face. I wish my children could live in peace.”[70]

Actors engaging in property grabbing are hard to reach, particularly for ongoing cases. For some insight, Human Rights Watch spoke with Ryann, the sister of an adult son who is currently harassing their mother to leave the homestead she built with her late husband in the 1960s. Her mother worked the land for 50 years with her husband, and they built a successful farm that is now being rented out, creating income that her brother has seized control over. Ryann describes the intra-family dynamics at play around the property grabbing, explaining:

My mother is 84 years old. She has diabetes and needs constant care. My sister pays for a caregiver, but my brother has sought to drive her [the caregiver] away by making public, false accusations that she is having sexual relations with a worker on the farm. I pay for groceries. My sister-in-law stole the groceries, and the police were called. They are all living in the same house. My sister-in-law also tells my mother that she is poor, and has nothing. This pains my mother.

My mother should be living peacefully, not having struggles with my brother. Police have advised that we should appeal to the High Court, but my other brothers are reluctant to take him [the bad actor] to court. They have talked with him, and he has agreed to be calm, but that has not lasted. My mother thinks it might be better to leave.[71]

Sometimes, widows reported that other widows of their husbands (who had polygamous marriages) had sought to grab their property. Della, 51, lives near Harare and married a man in a customary marriage who already had another wife. This other wife attempted to grab Della’s property after their husband died. She is trying to fight this through a court case with the assistance of Legal Resources Foundation, but is struggling in the meantime:

I live with my in-laws and the first wife together in the same homestead. My husband died in April 2015. I made a report [to the court] of no distribution of property in August of 2015. The first wife took custody of all the property of a sugar cane plot, cattle, and vehicles.

I want to support my children, who are 26 and 13. I do not have food for them, and I can’t send them to school. They have missed a year of school since the initial complaint [last year].

We are all staying in the same place. The first wife hired a private lawyer. She will not even greet me. Officials at the land ministry asked us to try to work it out, but she goes into her house and closes the door. This is very painful, it stresses me a lot. I do not know if I will prevail in court for justice. I just pray to God.[72]

Remedies

Widows need support from the moment they become widows, because from that moment, they become targets. They become vulnerable. I know that if we date or have a boyfriend, our property will be targeted…. People are not being faithful to [traditional] values of care and protection.

—Charity, 49, outside Harare, May 2016. Her husband passed away in 2007.[73]

Widows face significant difficulties accessing legal remedies for property grabbing. In many of the cases brought to the attention of Human Rights Watch, knowledge about property rights, inheritance rights, and civil and customary law on marriage were major obstacles to protecting widows’ property. Such hurdles, from lack of knowledge, to high costs, distances from rural homes to courts in urban centers, and cumbersome court procedures, limit widows’ access to equal rights to their property.

Many of the widows Human Rights Watch interviewed said that at the time of their husbands’ deaths, they had no clue as to how to challenge property grabbing. They do not know that their marriages should have been registered. Basic legal education on the radio is helping to get the word out in some areas, according to Tinomuda Shoko, a lawyer with Legal Resources Foundation, but it is not reaching widows in all areas and those not fortunate enough to have access to radios. An added complication is that older women have lower literacy rates than any other age group in Zimbabwe.[74] Thus widows require additional support to navigate the legal system.

|

Zimbabwe’s Legal Structures Available for Widows All estates are officially required to be registered when a person passes away. If the deceased had a civil marriage, or a “5.11” marriage, or if the deceased person had a will, the estate is to be registered with the High Court. If the deceased had a registered customary law marriage under the Customary Marriages Act or an unregistered customary union, the estate is to be registered with the Magistrates Court. Registration is required in person at the designated court office. A death notice or certificate and list of property must be provided to the court at the time of registration. Once the estate has been registered, the court contacts the registrant with a date for a return meeting to choose an executor.[75] Magistrates courts are located in each of the 61 districts of Zimbabwe. Some districts are very large, such as Hwange, which covers over 5656 square miles.[76] High courts are located in the two largest cities in Zimbabwe, Harare, and Bulawayo, and they hear appeals from the magistrates courts. Appeals from high courts cases are made to the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe. Some rural widows must traverse and pay for travel over long distances to arrive at these courts. For widows who are struggling, the limited availability of courts is a structural barrier to accessing justice and maintaining their rights to their property. |

Once a widow knows that she has a right to her property, she must navigate hurdles to have the marriage recognized, including seeking legal representation, paying relevant fees, keeping up with court appointments, and traveling to court, which can be many hours away. They told us that accessing courts could be daunting and confusing. Some widows give up before they have any remedy. Glynnis, 50, was married for 20 years before her husband passed away. His relatives chased her away from her home she shared with him, taking her belongings and her cattle as well. They refused to sign paperwork for her to receive her husband’s pension. She now lives in the home she grew up in, which her brother now owns. She said: “I have gotten nothing. I believe that this is unfair … [but] I have given up. I can do nothing [to stop it].”

Almost all the widows Human Rights Watch interviewed said they had to seek legal help before they were able to protect their property from in-laws intent on grabbing it. Once a widow has cleared the first hurdle of making contact with the formal legal system, laws like the Deceased Estates Succession Act delineate equal inheritance rights for women and men upon the death of a spouse. Taken at face-value, laws like this should help a widow to secure her property. But still the cards are often stacked against widows, most of whom had unregistered, customary law marriages and therefore have trouble proving they are a spouse for purposes of this law.[77]

Legal Resources Foundation lawyers said that obtaining confirmation of unregistered marriages is a challenge for them in representing widows, as there is no way to compel relatives of the deceased to tell the truth about the marriage. Lawyers said they often have to resort to alternative dispute resolution techniques such as external mediation because there is no legal tool within the system that balances the power that husbands’ families have to deny a marriage’s existence. “Recognition of unregistered customary law marriages is needed,”[78] one lawyer told us. “Some courts look for evidence [of a marriage] (such as lobola papers and photos from the birth of first child) and take it into account, but that isn’t automatic.”[79]

Going to court can be expensive, and processes can take years to complete. A lack of basic resources means that even relatively minor court fees or transportation costs can put a legal remedy out of reach for many widows. Over 70 percent of Zimbabweans live in poverty.[80] Some widows living in rural areas who spoke to Human Rights Watch specifically raised the obstacle of transportation costs such as bus fares to accessing courts in cities to claim their rights. To get around this, some had resorted to paying acquaintances located in cities to make inquiries for them. Others wanted to give up because of the expenses.

Lawyers told us that they frequently see these challenges. A number related stories of providing funds out of their own pockets to help indigent older widows. “Because magistrates courts are only located in provincial capitals, [some] widows need to travel for up to [six hours] each way on crowded buses to access these courts.”[81] On top of bus fares, widows need to forgo income-generating activities for that day or days; arrange for overnight stays if they cannot make the trip in one day; and have the physical stamina to make such a journey, which some older widows just may not possess.

Michelle’s husband died in 2012. Shortly after his death, her property was grabbed. Her in-laws took over the fields she had tilled for decades. They also stole the fruit from the trees in her kitchen garden and sold the harvest, leaving her without any livelihood. They also harassed, intimidated, and insulted her, attempting to chase her away from home by ganging up to physically surround and restrain her as they insulted her and told her to leave her home. She was fortunate to find legal representation from Legal Resources Foundation, but she still describes the struggles for transportation and court fees:

I could not even find the money for transport to the court, and the two fees of US$10 and $20. I struggled. The court said “take this paper there,” but I didn’t know what it was about. The court said that each person who has a stake in the property should share a fee of $131, but my in-laws said only I should pay. After that, a child of mine collected the $131, and the homestead was transferred into my name. I had to sell one of my two cows to [help] pay for this. The in-laws did not get anything.[82]

In many of the cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, a lack of knowledge about property and inheritance rights was a major obstacle to protecting widows’ property. Court processes were confusing and expensive for many widows. For widows like Michelle, it was overwhelming to manage engaging with courts before she found help through Legal Resources Foundation:

The police summoned the seven sons and my husband’s younger brother. They were served restraining orders in court, which also said that a formal distribution of property should be made.

An uncle said that an inventory was needed, and a death certificate, and that the magistrate’s court said that I should provide all of these things. I did not go to school, so I did not know what was required. The big challenge was that they said I should do everything.[83]

Over and over again, widows explained that their in-laws told them that they would apply customary law with regard to the distribution of the estate, like Charity’s relatives, referenced above: “At the funeral, my mother-in-law told me that the 5.11 Certificate [the certificate documenting a civil marriage] was just a piece of paper, and that they intended to follow cultural practices.”[84] With the announcement of this intention came the threat of property grabbing.

Just accessing things like a death certificate when a couple was in an unregistered customary union, a necessary document to change title to property, can be a challenge. Some did not know how to go about obtaining one, and the process does not appear to be uniform. One widow related that her husband passed away in a hospital, and she was given a death certificate along with the burial order. Others described how their in-laws took the burial order in order to attempt to obtain the death certificate from a registrar’s office. Many widows told Human Rights Watch that relatives of their husbands had to race to the registrar to attempt to obtain the certificate ahead of the widows. Relatives who succeeded falsely claimed that their brother or son did not have a wife, or had a different wife than the widow.

Several widows told us that all correspondence about court appearances were only communicated through male in-laws who, in some cases, withheld it from them to sabotage the proceedings. Zelda, 55, from Mashonaland East, for example, told Human Rights Watch that her marriage was registered but that after her husband died her in-laws attempted to obtain her property through a district court.

There was no will, but he [my husband] was clever and organized. The greatest protection, he believed, was a monogamous marriage. It's like he knew he might pass. He was always pushing, even when I was reluctant to go through the different steps to register our marriage.

[After he passed], neither I nor my in-laws knew about any procedures. In the high court, my elder brother-in-law brought marriage certificates, birth certificate, and death certificate. The high court said that they would get back to us.… My older brother-in-law [received] a letter about the next appearance in the high court, but he did not [tell me].[85]

She sought advice from Legal Resources Foundation at this point, and, with the marriage certificate and documents she had, it helped her gain control over her estate without her in-laws. She now collects her husband’s pension and can pay her son’s school fees.[86]

Gladys, 43, also complained about court appearance notices only going out to a male relative. She was the second wife of her husband, who had five wives. She married her husband when she was 14. She told us about her attempts to secure property when the first wife colluded with her husband’s family to eliminate the inheritance of the other four wives and children:

At the Harare master of the court, we were given a case number and asked to return in two weeks. We could not travel to Harare again, it was too expensive, and so I asked a relative to look into it for me. He said he needed a little money for transport and I agreed, then he said he needed a lot more, and I knew then that I could not rely on him. We couldn’t pay that money. With the cost of all of the back-and-forth, the other wives wanted to give up. One of my relatives in Bulawayo who worked for the police got me the phone numbers for the court so that I could call and check on our case.

In December 2015, the court organized a meeting in Harare through the son [of the first wife] on January 4, 2016. The son of the first wife contacted us on January 2, 2016, saying that they needed to have an inventory prepared. [On] January 2, he came to our house, and insisted we sign documents. We refused, saying we wanted to go to court. It was an affidavit saying his father left the [business location’s name redacted] plot to him, and it was not authentic. He did not tell us about the court date. The master of the high court called on January 4, 2016 to ask why we didn’t show to court. The son didn’t tell us.[87]

III. Legal Standards on the Rights of Widows

Under national, regional, and international law, Zimbabwe has to ensure the property and inheritance rights of widows. The treatment of widows documented in this report violates their rights to equality and freedom from discrimination, property, and access to justice, among others.

National Law

The 2013 Constitution of Zimbabwe supersedes all laws that run counter to it, including customary law.[88] It states that provision should be made for protection of any children and spouses upon the death of a spouse.[89] And on property rights, it states:

[T]he State and all institutions and agencies of government at every level must take practical measures to ensure that women have access to resources, including land, on the basis of equality with men.[90]

This meets or exceeds minimum international standards. Furthermore, it provides that “Every person has the right of access to the courts, or to some other tribunal or forum established by law for the resolution of any dispute.”[91] Under its own constitution, the government of Zimbabwe has committed to accessible courts.

Following the adoption of the new constitution, the government has begun an effort to bring all relevant national laws and regulations in line with it. According to the Ministry of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, 396 pieces of legislation have been identified for alignment with the 2013 constitutional amendment.[92]This process is slowly moving forward.[93] However, many of the laws and regulations that lie at the heart of the issues discussed in this report have not yet been amended.[94]

Zimbabwe has a constellation of formal, civil laws that apply to marriages and inheritance. The Married Persons Property Act states that marriages in Zimbabwe are not automatically community property institutions.[95] There is therefore no presumption that property in the marriage is jointly owned and inheritable by either spouse. Married people seeking to enter into a community property arrangement must do so before their marriage, filing a written agreement stating their arrangement with a local Deeds Registry office.

It is problematic that the Marriage Act and the Customary Marriages Act require the registration of only the marriages solemnized according to their rules.[96] No legal framework exists to protect the estimated 70 to 80 percent of unregistered customary unions rural women are living under in Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe’s Customary Marriages Act is part of its civil law, and the act offers many of the same protections to men and women in registered customary marriages.[97] It also extends parental rights and inheritance rights to children in unregistered, or “invalid,” customary marriages.[98] It does not protect the inheritance rights of a spouse in an unregistered customary marriage; however, the Administration of Estates Act does provide for equal rights for those in unregistered customary unions.[99] Further, the Customary Marriages Act specifically provides for consideration for a marriage, which in this context means lobola, and which runs counter to international human rights norms.[100]

The requirement of registration should be the same for all marriages. Processes for registration should be accessible throughout the country, including in rural areas, and the government should engage in necessary awareness-raising about the important benefits of registration to encourage it. Those with unregistered customary unions need an avenue to have their marriages recognized and to be given the opportunity for posthumous recognition, without the reliance on the testimony of in-laws. Without such an avenue for recognition and registration, the formal, civil law will continue to exclude widows in unregistered customary unions from its protection.

The Deceased Persons Family Maintenance Act and the Deceased Estates Succession Act, which address questions of marital property upon the death of a spouse, both appear to provide for equal inheritance rights for women and men upon the death of a spouse.[101] However, in practice, the results for widows and widowers are far from equal. The Deceased Persons Family Maintenance Act calls for estates to be administered according to the rules that would have applied if the marriage had ended in divorce, applying the Matrimonial Causes Act.[102] This law prohibits courts from exercising power over any property that was acquired by inheritance or custom or property that is of “particular sentimental value.”[103] In effect, any property that a husband had inherited (and nearly all property was inherited by men until relatively recently) continues to be out of reach for widows. The Deceased Estates Succession Act has a similar provision.[104] It provides only for occupancy and usage rights, not outright ownership.[105]

The Deceased Persons Family Maintenance Act provides that any person who “does an act with the intention of depriving another person of any [inheritance] right, or interferes with any other person’s right … shall be guilty of an offence and liable to a fine not exceeding level six or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year or to both such fine and such imprisonment.”[106] Such prohibition of property grabbing and punishment may be effective, if properly enforced.

Additionally, in some of the cases Human Rights Watch examined in the course of conducting research, customary laws were often interpreted and applied in a way that favors in-laws, even while those in-laws fail to fulfill the social expectation that they will protect and provide for widows. A 2004 research article notes:

Under customary law, the heir to the estate takes over all responsibilities of the house-hold head. It is therefore assumed that the duty to maintain [a widow and her household] will pass to him, though this duty is rarely fulfilled nowadays.[107]

A dozen years later, the widows Human Rights Watch interviewed would likely still agree with this observation.

African Human Rights Law Relevant to Widows

Zimbabwe is a party to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, which enshrines the principles of non-discrimination based on sex, and protection based on old age.[108] The charter calls on states to eliminate "discrimination against women" and to ensure the protection of the rights of women, as specified in international human rights conventions.[109] The charter also requires states parties to ensure the protection of the right to property.[110] The African Union has articulated the rights of widows and older women even further in additional protocols and resolutions.

In April 2008, Zimbabwe ratified the African Union Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol), which contains a number of critically important provisions on property rights for women and widows. The protocol specifically mentions the right of equal protection and benefit of the law (article 8), and states parties are required to take "appropriate legal measures to ensure that widows enjoy all human rights."[111] Article 6 of the protocol requires that "every marriage shall be recorded in writing and registered in accordance with national laws, in order to be legally recognized," and article 7 states explicitly that when a marriage ends, "women and men shall have the right to an equitable sharing of the joint property deriving from the marriage."[112] Specific rights in widowhood include equitable rights to property, as well.[113] Article 25 also requires states to provide appropriate remedies for violations of the rights in the protocol.[114]