On November 29, 2019, young people will gather at locations around the world for a Fridays for Future Global Climate Strike. On December 2, United Nations delegates, world leaders, business executives, and activists will meet at the 25th Conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP25) in Madrid to discuss ways to protect the environment. Participants in these events should also discuss ways to protect the protectors: the individuals and groups targeted around the world for their efforts on behalf of the planet.

The dangers facing environmental defenders do not stop at accusations that they are national security risks. From the Amazon rainforest to South African mining communities, activists seeking to preserve ecosystems and ancestral lands are being threatened, attacked, and even killed with near total impunity, Human Rights Watch has found. But in contrast to many of these illegal acts, the unjust labeling of environmentalists as security threats is often more insidious, as it is generally carried out under the color of law.

And while not all environmental activism is peaceful, only in exceptional cases would the actions of environmental activists meet a generally recognized definition of terrorism – actions aimed at terrorizing populations by causing or threatening death or serious physical harm to others to advance an ideological or political agenda. Nor, in nearly all cases, do their actions aim to undermine the rule of law. Typically, these individuals and groups are peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of speech, association, and assembly. When they engage in civil disobedience, their aim is usually to strengthen – and improve the enforcement of – existing environmental protection measures. Here are a few examples where environmental activists have been smeared as terrorists or other national security threats:

In Poland, the authorities denied entry in December 2018 to at least 13 foreign climate activists who were registered to attend COP24 in the southern city of Katowice, contending they posed a threat to public order and national security. Along with other individuals and groups, the activists had planned to press COP24 participants for rapid action to address climate change.

The authorities had previously passed a special law empowering the police to collect data about conference participants without judicial oversight or the participants’ knowledge and consent and ban spontaneous protests during COP24. They also issued a terrorism alert that authorized increased vehicle checks and other security controls for Katowice and surrounding areas for the duration of the summit. Border officials detained and questioned several activists for hours, in some cases without allowing them to communicate their location or contact a lawyer.

In November 2015, French police used a sweeping counterterrorism emergency law enacted in response to the deadly Paris attacks earlier that month to place at least 24 climate activists under house arrest without judicial warrant, raid activists’ homes, and seize computers and personal belongings.

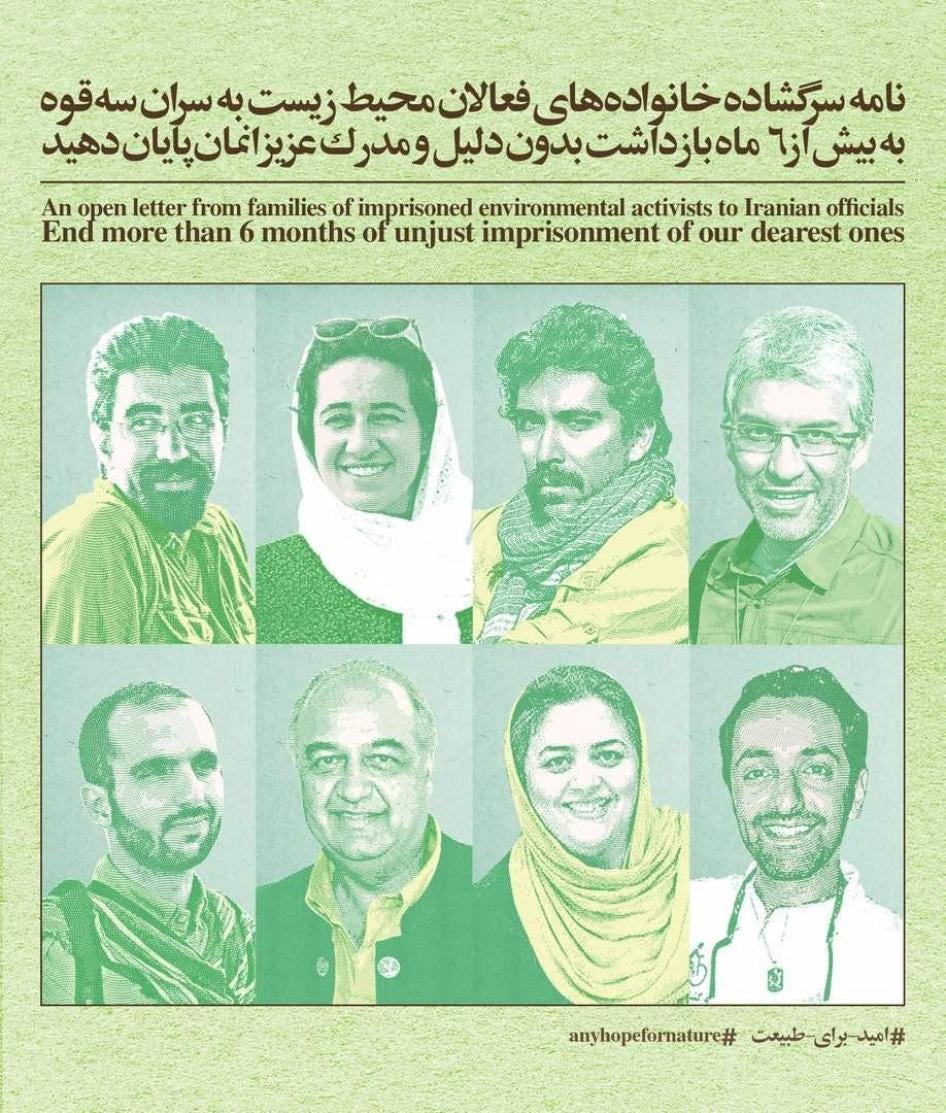

The activists were accused of flouting a ban on organizing protests related to COP21, which was being held in France the following week to sign the Paris Agreement on reducing emissions that contribute to global warming.In Iran, six members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation (PWHF), imprisoned since early 2018, were handed prison terms of up to 10 years in November for allegedly spying for the United States. During a deeply flawed trial, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards said the environmentalists used their work to protect the Asiatic cheetah – one of the world’s most endangered species – as a cover. A charge against four of the accused of “spreading corruption on Earth,” a crime that can carry the death penalty, was reportedly dropped in October. Two other PWHF members also detained in early 2018 were awaiting judgment. A ninth environmentalist, PWHF founder Kavous Seyed Emami, died a few weeks after his arrest under suspicious circumstances in what the Iranian authorities alleged to be a suicide.

Issa Kalantari, the head of Iran’s Department of Environment, said there was no evidence that the detained environmentalists were spies. He said the arrests have had a chilling effect on environmental groups in the country.

The arrests appear to be motivated both by Iran’s “paranoia” about foreign countries using environmentalists as cover and its recognition that anger over environmental degradation can unite populations against government policies, said Kaveh Madani, the country’s former deputy environmental director. Madani returned to his native Iran from London in 2017 to take up the post, but said he was immediately detained and questioned by Revolutionary Guards, who broke into his phone, computer, emails, and social media accounts, and called him a “bioterrorist,” a “water terrorist,” and a spy. He left Iran after seven months, alleging repeated harassment including for his criticism of dam projects, which are constructed by the Revolutionary Guards.

In Kenya, the police and military have frequently labeled environmental activists opposing a mega-infrastructure project in the Lamu coastal region, including a coal-fired power plant, as “terrorists” while subjecting them to threats, beatings, and arbitrary arrests and detentions. In 15 cases documented by Human Rights Watch between 2013 and 2016, the authorities accused environmental defenders of membership in, or links to, the extremist armed group al-Shabab but provided no compelling evidence.

The activists are protesting construction of the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor, the biggest infrastructure project in Central and East Africa, which is to include a 32-berth seaport, three international airports, a road and railway network, and three resort cities. They contend that LAPSSET will pollute the air and water, destroy mangrove forests and breeding grounds for fish, and take farmland without just compensation, displacing communities and destroying their livelihoods.

In July, Kenya’s environmental tribunal blocked approval of the power plant absent a new environmental impact study, finding the China-backed developers’ original assessment and public consultation process inadequate. The rest of the LAPSSET project continues. So does the intimidation campaign, activists protesting LAPSSET told Human Rights Watch.

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte in 2018 placed 600 civil society members, including environmentalists and indigenous rights defenders, on a list of alleged members of the country’s communist party and its armed wing, which he declared to be a terrorist organization. Duterte’s “terrorist list” included Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous Filipina who is the UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples and a climate change activist.

In late 2017, Tauli-Corpuz had criticized the government for attacks and other abuses against indigenous communities that opposed coal and diamond mining on ancestral lands. Although a Manila court months later ordered the government to remove Tauli-Corpuz from the list, a Philippines military official in 2019 renewed the campaign against her, accusing her of “infiltrating” the UN for the communist insurgents. Several UN human rights experts condemned Tauli-Corpuz’s listing.In Ecuador, eight years passed before the prominent environmental activist José “Pepe” Acacho, a Shuar indigenous leader, was able to clear himself of “terrorism” charges for his activities opposing mining and oil exploration in the Amazon. Acacho was charged with terrorism in 2010 for allegedly inciting violence during Shuar protests against a mining law.

He was convicted in 2013 and sentenced to 12 years in prison. Human Rights Watch reviewed the trial documents and found no credible evidence of terrorism-related crimes. In 2018, Ecuador’s highest court threw out the terrorism conviction but instead sentenced him to eight months in prison for “public services obstruction” – a charge for which he was never tried and hence never had the opportunity to contest. Acacho spent 17 days in jail before receiving a presidential pardon in October 2018.In the US in August 2018, then-US Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke blamed “environmental terrorist groups” that opposed logging for wildfires on the West Coast – a proposition immediately attacked by leading environmental organizations including the Sierra Club. In 2017, 84 members of the US Congress, most of them Republicans, asked the Justice Department if activists mobilizing against the construction of oil pipelines could be prosecuted as terrorists. (The department’s response was that in some cases, yes.)

That same year, a major pipeline operator, Energy Transfer Partners LP, filed a lawsuit against Greenpeace and other environmental groups, accusing them of launching a “rogue eco-terrorist” campaign against the Dakota Access crude oil pipeline. Environmental activists and Native American tribes had tried to block construction of the 1,172-mile-long, underground pipeline through North Dakota during a protracted standoff with the authorities in 2016, saying it threatened sacred sites and drinking water. A federal court dismissed the lawsuit earlier this year.

Although the protesters were largely peaceful, some resorted to violence and were convicted of protest-related crimes, but none for offenses that even remotely approximated terrorism. UN experts condemned security force responses to the protests as “excessive,” including their use of rubber bullets, teargas, compression grenades, mace, and “inhuman and degrading” detention conditions.

In Russia, at least 14 environmental groups have stopped work in recent years, and the head of the prominent group Ekozaschita! (Ecodefense!), Alexandra Koroleva, fled the country in June to avoid prosecution under the draconian Law on Foreign Agents. The 2012 law requires any Russian group accepting foreign funding and carrying out activities deemed to be “political” to register as a “foreign agent,” a term that in Russia implies “spy” or “traitor.” Authorities have used the law to silence groups that opposed state-sanctioned development projects and petitioned authorities for the release of imprisoned environmental activists, a Human Rights Watch investigation found.

Russian officials including the special envoy for environmental protection, Sergey Ivanov, have applied the “extremist” label to Greenpeace Russia. An activist with Stop GOK, a Russian group seeking to block mining and enrichment plants, was fined in April 2019 for “mass distribution of extremist materials” because he published a poem on the organization’s social media page that the government had banned as extremist in 2012. The Russian nongovernmental organization SOVA Center, which analyzes counter-extremism trends, found that the poem, “Last Wish to the Ivans,” is a satirical address to destitute, alcohol and drug-addicted Russians from oligarchs and authorities profiting from extracting natural resources.

Stop GOK and Greenpeace Russia were among groups named in a 2018 report by pro-government technologists as “environmental extremists” working for “influential forces in the West” bent on sabotaging strategic industries. The report was widely covered by state-controlled media.

Civil society participation will be crucial to ambitious outcomes at COP25. Parties to the summit, which include all UN member countries and the European Union, should allow activists ample opportunity to air their concerns about the climate crisis and use their combined expertise to help identify solutions. They should also provide activists with a safe space to speak out about the threats they face for carrying out their work.

In addition, parties should publicly commit to robustly carrying out international and regional treaties that protect environmental defenders. One of these treaties is the Escazu Agreement (the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean), the world’s first covenant to include specific provisions promoting and protecting environmental defenders. Twenty-one countries have signed the 2018 agreement. But only six countries have ratified it – five shy of the ratifications needed to enter it into force. Chile, which stepped down as COP25 host because of protests stemming from economic grievances, but will still preside over the negotiations in Madrid, should lead by example and ratify the agreement.

COP25 participants should also commit to upholding the Aarhus Convention (the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters), to which Spain is a signatory. The convention – an environmental pact for Europe, the European Union, and Central Asia – grants the public, including environmental groups, an array of rights including public participation and access to information and justice in governmental decisions on the environment, without harassment or persecution. Parties to the treaty, including the EU, and Poland for its crackdown at COP24, have been criticized – including in some cases by the Aarhus Convention’s own oversight body – for flouting these provisions.

COP25 delegates should recognize that to genuinely protect the environment, they also need to protect its defenders – including those unjustly targeted in the name of security.