Summary

On May 25, 2018, police arrested two activists during a peaceful protest in Lamu town, Kenya. The activists, staff of the environmental groups, Save Lamu and Lamu Youth Alliance, were protesting the government’s decision to proceed with construction of a power plant despite environmental and health concerns. Police held them at Lamu police station for six hours for participating in an “illegal assembly.” They were not charged.

Two days earlier, police received the required notification of the protest from Lamu Youth Alliance. Under Kenyan law, protesters are allowed to picket, and police have no power to arrest demonstrators in the absence of evidence of a crime. The experience of these activists is symptomatic of the obstacles activists face when opposing the planned power plant and other development projects at Kenya’s coast region.

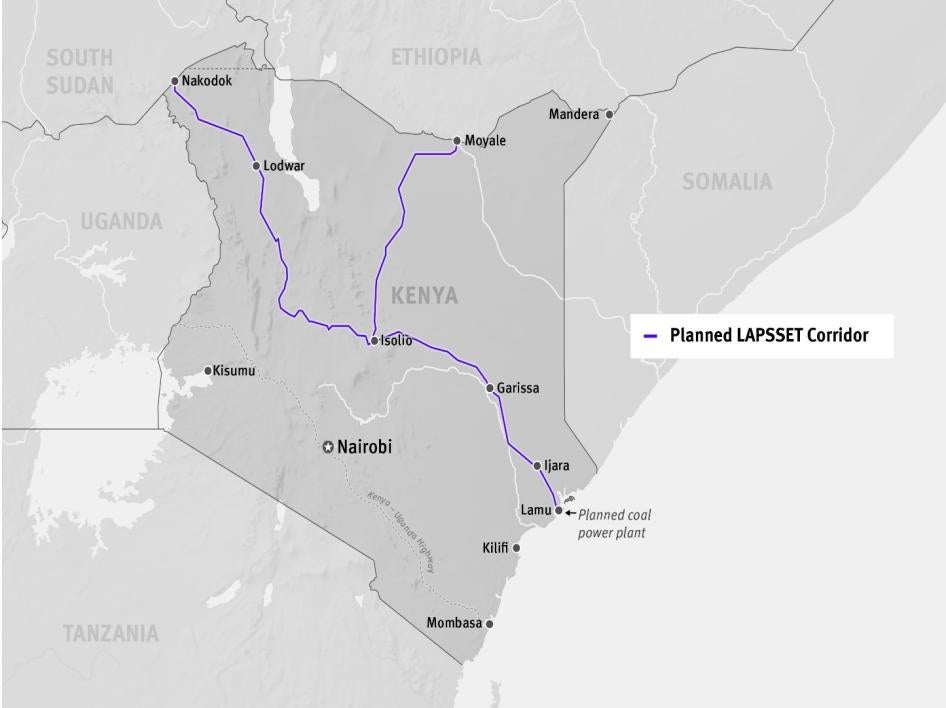

The power plant is only the latest in a string of planned projects that make up an ambitious, longstanding regional project known as LAPSSET, the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport corridor project. Other planned projects include an oil and gas pipeline from Lamu to Turkana, and oil and gas drilling that is mainly on Pate Island as well as Lamu port and an airport on Manda Island. As the Kenya government moves ahead with financing and implementation of these projects, communities on the coast have become increasingly concerned about the potential adverse health and environmental impacts as well as inadequate compensation for land acquired by the projects.

For at least six years, Kenyan and international groups have campaigned both to raise awareness about the environmental and health risks of the various components of LAPSSET and, as in the case of the power plant, opposed the project. Activism around the issue made national news when in late 2014 police raided the offices of Save Lamu and summoned key staff for interrogation in Nairobi. Yet, despite harassment and intimidation by authorities, activists have kept up the pressure against LAPSSET and associated projects.

In June 2018, environmental activists from across Kenya held a peaceful demonstration in Nairobi against the power plant, attracting international support. In January 2018, the European Union ambassador to Kenya urged the government to drop plans to construct the plant in line with the global drive for clean energy such as wind and solar power that, unlike coal, have low levels of pollution.

Based on research conducted between May and August 2018 by Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders, this report documents cases of harassment and intimidation against at least 35 environmental activists by police or military and other government officials. The activists include, members of civil society organizations, fishermen and farmers who are generally targeted while engaged in activities such as public interest litigation, holding public meetings and, in a few instances, organizing peaceful demonstrations.

Researchers interviewed 97 people in the Lamu Archipelago, including the affected activists, community leaders, environmentalists, fisherfolk, lawyers representing activists, police and other government officials as well witnesses of the abuses against activists.

This report focuses on obstacles and abuses confronting activists and residents of Lamu County who have spoken up about various issues, including those related to the impacts of largescale projects – especially the port and power plant – on the environment and on livelihoods, especially of fishermen. They have also complained of the adverse economic effects of land acquisition for the various components.

The activists argued that the power plant will emit smoke that contains hazardous particulate matter, discharge waste effluents into the sea that could kill fish and other sea animals, and further emit coal dust that poses serious health risks to those residing near coal plants, including cancer. The activists said the construction of the port and other components could also destroy mangrove forests and breeding grounds for fish and other marine animals, taking away farming lands with compensation yet to paid for most of them, risks of water pollution due to the waste discharge and climate change brought about by greenhouse gas emissions. This report documents abuses activists faced for raising these concerns.

The focus of our research was the obstacles faced by activists speaking up about these issues. Police and military officers in Lamu have broken up peaceful protests, banned public meetings by activists, threatened, arrested and prosecuted activists on various charges. In 2016, two activists disappeared; one of them is presumed dead, after being arrested. In at least 15 instances, police accused activists of having links or being sympathetic to Al-Shabab, a Somalia-based militant Islamist group that has carried out numerous attacks in Kenya.

Government authorities have responded by denying knowledge of these abuses and casting suspicion on the motivations of the organizations and activists – which they said are influenced more by donor money rather than genuine concern for the environment. Such hostility and dismissive attitude have discouraged activists from reporting abuses and pursuing justice.

Kenyan authorities have an obligation to respect the role of activists and to uphold the right to health and a healthy environment, freedom of expression, association and assembly as outlined in various international treaties and conventions, the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, and Kenya’s constitution. There is also an emerging set of international norms protecting human rights defenders, including environmental activists, that Kenya can and should promote by ensuring accountability for unlawful repression.

The Lamu activists represent a test case for Kenya to uphold and protect rights in the context of largescale development projects. As the LAPSSET and related projects gain momentum, and as Kenya initiates numerous other development projects across the country, the government should provide space for and protect community engagement – even by those who oppose the projects.

Human Rights Watch and NCHRD’s urge the authorities to address the abuses documented in this report, even though Kenyan authorities have a history of rarely holding police officers implicated in abuses to account. The Inspector General of Police should ensure prompt, thorough, independent and effective investigation of the threats and arbitrary arrests, including the deaths and disappearances of activists, and address the failure to adequately investigate such cases, especially by strengthening the work of police accountability mechanism in Lamu.

The Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), a civilian police accountability institution, should investigate security officers for intimidation, harassment, threats and unfair prosecutions of activists in Lamu county.

The Director of Public Prosecutions should initiate prosecutions against any security and government officials credibly implicated in the abuses against activists.

Recommendations

To the President, National Government and County of Lamu

- Direct government officials to, in line with the international best practices such as United Nations declaration on human rights defenders, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights or the UN declaration on the right and responsibility of individuals, groups and organs of society to promote and protect universally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect and protect the work of activists across Kenya in general and, in this case, the work of environmental rights activists in Lamu county.

- Publicly condemn assault, threats, harassment, intimidation and arbitrary arrests of Lamu activists, and direct security and other government officials to stop arresting, harassing or threatening activists on false accusations, including links to Al-Shabab.

- Direct the Inspector General of Police to ensure prompt, thorough, independent and effective investigation of the threats and other forms of intimidations or harassment, including disappearance of activists, and adopt a plan that would address the failure to adequately investigate such cases.

- Direct police and the Director of Public Prosecutions to ensure accountability for state officials, regardless of rank or position, who threaten, harass, or arbitrarily arrest activists who express concerns about the effects of LAPSSET and coal power plant to the environment and economic livelihood of the people of Lamu.

- Encourage government officials to consult widely with all interested groups in addressing the numerous environmental, health and livelihood concerns arising out of LAPSSET and associated projects, including environmental and health concerns.

- Encourage state agencies and relevant private companies to respect applicable national and international law in the implementation of LAPSSET, including respect for freedom of assembly and speech and the right to a healthy environment.

To the Inspector General of Police, National Police Service Commission, Independent Policing Oversight Authority

- Direct all police officers, particularly those attached to county offices, to respect and protect the work of activists across the country.

- Investigate all reported cases of attacks, threats, and harassment of activists in Lamu and ensure that all those found responsible are held to account.

- Investigate any reported cases of officials, regardless of rank or position, threatening, harassing or arbitrarily arresting activists in Lamu county and across Kenya.

To the Director of Public Prosecutions

- Direct the Inspector General of Police to ensure investigations into all reported cases of harassment and intimidation of activists in Lamu county and other parts of Kenya.

- Direct the Independent Policing Oversight Authority and the Kenya Police Service to investigate reports of abuses by police and other government officials against activists in Lamu county and other parts of Kenya.

- Prosecute any members of the security forces where there is evidence of their being complicit in crimes against activists in Lamu and other parts of Kenya.

To the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, Commission on Administrative Justice

- Investigate state officials credibly implicated in intimidation and harassment of activists in Lamu county and across Kenya.

- Initiate prosecutions against any members of the security forces or government officials where there is evidence of complicity in the harassment and intimidation of activists.

To the Ministries of Energy, Transport and Lands, National Environment Management Authority and the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority

- Encourage relevant officials to work closely with activists to ensure environmental and land compensation concerns relating to LAPSSET and associated projects are adequately addressed.

- Ensure that, while implementing the various components of LAPSSET project in Lamu county, the affected communities are adequately informed and therefore able to fully participate in decision making.

- Urge police and the Kenya Defense Force officers to stop harassing and intimidating activists in Lamu and other parts of Kenya and ensure that those implicated in such violations are prosecuted.

To Private Project Companies involved in LAPSSET

- Ensure compliance with national and international requirements for undertaking developments, including taking adequate measures to address any environmental concerns and respecting the rights of environmental activists.

- Conduct human rights due diligence to identify any risks, including those posed by police, military or other government officials, and take actions to prevent or mitigate them.

To the International Community, Including the United Nations Environment Program and Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Publicly speak up on the importance of the Kenyan authorities to respect and protect the work of activists across the country, and particularly those currently focusing on LAPSSET and associated projects, and further urge the Kenya government to restrain security agencies and other government officials to stop harassing activists.

- Urge Kenyan authorities to investigate reports of harassment and intimidation of environmental and land rights activists working on issues related to key state development projects in Lamu county.

- Provide support to activists and environmental groups focusing on LAPSSET, coal power and oil and gas in Lamu county, and urge Kenyan authorities to address the main concerns arising out of these projects.

- The UN Office of Counter Terrorism, the UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Executive Committee (C-TED) and the UN Special Rapporteur on Countering Terrorism should press Kenya to refrain from arbitrarily labeling activists as Al-Shabab sympathizers.

Methodology

This report is based on research by Human Rights Watch and National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders -Kenya (NCHRDs) in Lamu county between May and August 2018. Human Rights Watch and NCHRDs interviewed 97 activists, including eight community leaders, environmental experts, fishermen, lawyers representing activists, police officers, including the Lamu County police commander, and five other government officials. Interviews were conducted with activists and community leaders primarily from the three main Islands of Manda, Lamu, and Pate. Interviews were also conducted with activists and community leaders in Kwasasi area, north of Lamu town.

Interviews were conducted in secure locations where interviewees felt comfortable, mostly in Swahili, but in some cases with the help of interpreters. Researchers identified interviewees with the help of local groups working on environmental and economic rights in Lamu. Accounts of witnesses and victims were further cross checked with other independent sources, including police, other government officials and existing documents. The names and other identifying details of some interviewees have been withheld to prevent possible reprisals.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be collected and used. All orally consented to be interviewed. Most interviews were conducted at a location that was mutually agreed.

On July 6, Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition on Human Rights Defenders (NCHRDs) requested a meeting with cabinet secretaries of the Ministry of Lands and the Ministry of Energy on the main environmental concerns relating to LAPSSET and the coal powerplant, and the allegations of harassment of activists working on those issues (see appendix I). At time of writing, the ministries had not responded to our request for a meeting.

On October 1, 2018, researchers met senior officials of Amu Power and Gulf energy to discuss some of the issues that emerged during our research about the plight of environmental activists in Lamu.

On November 20, we shared our preliminary findings with the Inspector General of Police, LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, Amu Power, Gulf Energy and Centum Investment Company on alleged human rights abuses related to land confiscation (see Appendix II). Amu Power, through their lawyer, responded in a letter dated December 10 (see appendix III). Human Rights Watch and NCHRDs did not receive a response from the Inspector General or the other institutions by the time of publication.

I. Background

Lamu County

Lamu County is one of the six counties in the former Coast Province and sits on the eastern coast of Kenya on the Indian Ocean. The county has two constituencies, Lamu East and Lamu West. The Lamu Archipelago, site of the government’s big infrastructural projects, cuts across both Lamu East and West and is a predominantly Muslim part of the county that consists of Lamu, Manda, and Pate Islands, as well as several smaller islands.[1] Lamu Old Town on Lamu Island, in Lamu West, is considered one of the oldest and best-preserved Swahili settlements in the region and has been designated a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site. As such, Lamu’s economy relies significantly on tourism, in addition to fishing for local consumption and export.[2]

Impact of Al-Shabab Attacks

Since 2010, the county has suffered attacks attributed to the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab.[3] In October 2011, following increased Al-Shabab activity in different parts of the country, including Lamu, Kenya sent its military across the border to pursue the group in Somalia. Al-Shabab stepped up deadly attacks at the coast and the northeastern regions of Kenya.[4] The attacks became so frequent that, by August 2014, state officials said Kenya had experienced over 100 terrorist attacks in the preceding three years, 11 percent of them in Lamu county alone.[5] Kenyan authorities have responded to these attacks in the northeast, Nairobi and at the coast with abusive operations, including harassment and intimidation of human rights and environmental groups carrying out legitimate and peaceful activities.[6]

This follows a now familiar pattern in other parts of the country. In April 2015, the Inspector General of police included two Mombasa-based human rights groups, Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI) and Haki Africa, in an official list of supporters of terrorism and froze their bank accounts.[7] The two organizations successfully challenged the listing in court.[8]

A similar pattern is playing out in Lamu, where police have accused organizations and individual activists campaigning against LAPSSET of having links to Al-Shabab without providing any compelling evidence.”[9]

LAPSSET and Other Coastal Development Projects

Over the past six years, Lamu County has been at the center of some of the biggest and most expensive infrastructure projects undertaken by the Kenyan government in its efforts to turn the country into a middle-income economy by 2030.[10] The most ambitious of these projects is the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor designed to link Kenya with neighboring South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda with an oil pipeline, refinery, railways and network of highways. [11] It is the single largest infrastructure project in East and Central Africa in many decades and includes plans to construct a 32-berth seaport in Lamu; three international airports in Lamu, Isiolo and Turkana; three resort cities in Lamu on the east coast, and Isiolo and Turkana to the northwest.[12] The total cost of these various components of LAPSSET project is estimated at US$25.5 billion, funded through public-private partnerships and beneficiary countries.[13]

Kenyan authorities predict that the project will boost the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by two to three percentage points.[14] They argue that it will improve livelihoods and cut overdependence on the main port of Mombasa and the existing, overused Mombasa-Nairobi-Uganda corridor through creation of a second transport corridor.[15] The then Kenyan president, Mwai Kibaki officially launched LAPSSET in March 2012 in the presence of South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and then-Ethiopian President, Meles Zenawi, now late. Both Meles and Kiir expressed support for the project at the time.[16] The support of the project by Ethiopia and South Sudan has however appeared to wane.

A major element of the LAPSSET corridor is the Lamu Port project, constructed by the Government of Kenya through the Ministry of Transport.[17] The plan is to construct 32 deep sea berths, which is estimated to cost $5 billion.[18] The first three berths will be financed by the Government of Kenya, the first of which is expected to be completed by late 2018.[19] According to media reports quoting government officials, Chinese company China Communications Construction Company won the tender to construct the first three berths of the port.[20] Private investors are expected to fund the remaining 29 berths.[21]

Other development projects in Lamu include a coal-fired power plant, to be constructed in Lamu West, which the LAPSSET authority describes as an associated project.[22] In 2016, the Kenya government awarded a concession to Amu Power Ltd., a joint venture company led by Kenyan companies Gulf Energy Limited and Centum Investment Company Ltd., and joined by Chinese company, Power Construction Corporation, among others.[23] The consortium will construct and operate the $2 billion plant on a 975-acre piece of land. Amu Power also recently signed an agreement with American corporation General Electric to provide central technological components for the coal power plant.[24] The plant is designed to generate 1,050 Megawatts and is part of the LAPSSET Corridor.[25]

Construction of the plant has been delayed for several years due to a combination of factors, including administrative challenges such as petitions to the National Environment Tribunal, a body that hears disputes arising from National Environmental Management Authority’s issuance, denial or revocation of licenses, and court challenges.[26] Amu Power said the construction of the plant has not broken ground.[27] From the start when government first announced the project, community organizations opposed the project.[28] In August 2016, a Kenyan court suspended construction of the coal plant following a petition by activists against the national power company and the project proponent.[29]

The petitioners challenged Amu Power’s environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA). The assessment noted that despite air “pollutants and dust,” “noise by construction plant and equipment,” sewerage that could adversely affect the environment, and changes in the drainage regime and increased erosion, “there are no flaws that could prevent the project from proceeding, provided mitigation and management measures are implemented.”[30] While the petition was pending in 2016, the National Environment Tribunal stopped all construction in accordance with the Environmental Management and Coordination Act of 1999, which says any project stands suspended if a complaint is filed against it.[31]

In March 2018, a judge in Malindi dismissed a case in which activist Okiya Omtata and Katiba Institute, a Nairobi based NGO, demanded human rights due diligence before construction could proceed.[32] The judge ruled that the relevant authorities had complied with all statutory requirements and that the complainants ought to have voiced their concerns much earlier at the public participation stage.[33] In September, a Nairobi judge, while ruling on an appeal to the dismissal, restored the stop orders from 2016.[34]

Activists alleged that a natural gas exploration project on Pate Island, closely associated with LAPPSET, could also have significant impact on the environment.[35] Although prospecting for oil and gas in various parts of Kenya, and particularly in Lamu County, has been ongoing for close to a decade now, the first phase of natural gas exploration on Lamu’s Pate Island only started in earnest in early 2018 and there have been no extractions yet.[36]

Health, Environmental Impact and Effects on Livelihoods

While there has been some optimism around the anticipated economic benefits of the LAPSSET and associated projects, such as increased access to electricity and more jobs, activists and residents of Lamu County have expressed concerns about the impacts of largescale projects on the environment, health and on livelihoods, especially of fishermen, and the economic effects of land acquisition, such as reduced source of income for families, for the airport and coal-fired power plant projects.

The activists, who have teamed up with others across Kenya to coalesce under a global campaign called “deCoalonize,”[37] argued that the planned Lamu coal power plant will emit smoke that contains hazardous particulate matter, discharge waste effluents into the sea that could kill fish and other sea animals, and further emit coal dust that poses serious health risks to those residing near coal plants as well as children, the elderly, pregnant women, and people with lung conditions.[38]

Specific studies looking at the impact of coal-fired power plants on the health of surrounding populations have been conducted in China, India, Canada, the United States and Europe finding increased mortality and morbidity attributable to the release of toxic metals and particulate matter into the air. While exposure to emissions also depends on factors such as weather (temperature, precipitation, wind-direction and speed) and topographical features of the local area, emissions can be transported long distances, even globally, causing health effects to those living far from power plants. A recent study in Spain estimated the attributable impact from coal-fired power plants to include 709 premature deaths (mainly cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as deaths due to malignant tumors); 459 hospital admissions due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, 10,521 cases of asthma symptoms in asthmatic children, 1,233 cases of bronchitis in children and 387 cases of chronic bronchitis in adults.[39]

A senior official of Gulf Energy told researchers the authorities have since 2017 upgraded to the more advanced ultra-super critical technology–a technology embraced by coal power production advocates worldwide–in a bid to address these concerns. [40] Other scientists have pointed out that, while “ultra-super critical technology” increases the efficiency of the plant in burning coal, it does not eliminate particulate matter emissions or even address the problem of air pollution.[41]

Ultra-supercritical plants emit 98 percent as much carbon as supercritical plants and 91 percent as much as subcritical plants. Furthermore, the designations of subcritical, supercritical, and ultra-supercritical reveal nothing about whether the plants will control the sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and mercury emissions from coal combustion.[42]

Save Lamu, a coalition of more than 40 Lamu based environmental groups,[43] Lamu Youth Alliance, a youth initiative that is also part of Save Lamu,[44] and other environmental groups and independent activists campaigning against the coal plant and LAPSSET in general have focused on the potential destruction of mangrove forests and breeding grounds for fish and other marine animals, risks of water pollution due to the waste discharge, climate change brought about by greenhouse gas emissions, and the threats the projects could pose to livelihoods.[45]

Amu Power stated that their involvement with the Lamu community includes fresh water delivery, donation of nets and other equipment for fisherman groups, assisting the county government in providing street lights and block paving; and launching an afforestation program with the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI).[46]

Accountability Counsel, a US based organization that assists people to defend their rights and seek accountability for internationally financed projects, estimates the coal plant could deprive more than 3,000 artisanal and fisherfolk of their traditional fishing grounds.[47] Activists are further concerned that ongoing dredging for the Lamu port along the Indian ocean shores have destroyed fish breeding grounds there and interfered with fish movements.[48] Both the Lamu activists and Accountability Council are concerned that these massive development projects, which are displacing populations and destroying environment, could potentially destroy Lamu’s rich culture and thus undermine its position as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[49]

An umbrella association for fishermen, the Lamu Fishermen’s Association, said dredging for the Lamu port– a LAPSSET component– has destroyed mangrove forests, sea grass and coral reefs, which are nesting areas for fish and turtles.[50] As a result of the destruction of breeding grounds, traditional fishing waters are less bountiful, and fishermen must now travel further and longer to make catches in riskier parts of the deep sea with rougher waters.[51]

In 2012, a group of Lamu Archipelago fishermen filed a lawsuit against various government authorities alleging that LAPSSET would violate residents’ right to a clean and healthy environment and that there was lack of public participation in the project. The fishermen also argued that LAPSSET violated their fishing rights, for which they were entitled to compensation. In May 2018, the High Court ordered the government to pay over 4,700 fishermen Ksh1.7 billion ($17 million) and ruled that the government had violated the community’s cultural rights, right to a healthy environment and right to earn a living.[52]

At time of writing, the government was yet to pay the compensation, claiming that they were still reviewing which fishermen were entitled to receive payment. Authorities argued that because of the many now posing as fishermen since the court decision, the number of those claiming payment appeared to be well above the 4,700 genuine fishermen in the county.[53]

Government officials told Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders that as part of the response to residents’ concerns about deprivation of livelihoods, authorities launched a scholarship program worth Ksh11 million ($110,000) in Lamu County, which would benefit a total of 1,000 people in five years. The program is expected to provide local youth with the education and other skills to eventually secure jobs once the Lamu port and other components of LAPSSET are complete.[54] Activists in Lamu told researchers that the scholarships program lacked transparency and proper criteria on how to choose beneficiaries and as a result, it was unclear how many Lamu youth had benefited so far.[55]

Amu Power said that the company has not opposed any demonstrations over the power plant, and that they believe “everyone has the right [to] express their opinions on the Coal Fired Power Plant in line with the constitutional protection of freedom of expression and freedom of assembly demonstration and petition.”[56]

Inadequate Consultation

Kenyan law provides for mandatory public participation in decision-making processes in relation to government projects that affect them.[57] But activists in Lamu argued that the Kenyan government has not carried out appropriate consultation with local communities and residents before embarking on these projects.

In the fishermen’s suit discussed earlier, the Nairobi High Court found the government did not meet the requirements for either prior or continuing consultations with affected communities, violating the cultural rights of indigenous people as enshrined in Kenya’s constitution and other international treaties.[58] The court also found that Kenyan authorities had not provided the community with adequate information about LAPSSET before implementation began, thus violating the right to information.[59]

The court decision was in line with international law. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) requires states to consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples through their own representative institutions in order to obtain free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing measures that may affect them.[60] The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights has required the government of Kenya to apply this standard concerning indigenous peoples in Kenya.[61]

Other community leaders made similar arguments. An official of Lamu’s Kililana Farmers Association told researchers that while some residents learned about LAPSSET through the media, most did not know about it until heavy machines were deployed for ground breaking in 2012.[62] A staff member recounted: “It was only after we protested that the authorities withdrew the machines.”[63] Kenyan government officials subsequently held meetings with community leaders from 2012 up to 2014 and determined a compensation package for land owners, which remains a subject of dispute (described below) between communities and the government.[64]

Amu Power said that since 2015, the company has collated views and objections to the proposed power plant, holding 31 “stakeholder engagement meetings” and 1,000 sensitization visits, and several forums attended by diverse groups with” all views, including divergent views, being expressed freely.”[65]

Grievances Over Land Acquisitions

The 2013 report of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) found that Lamu county faced land-related conflicts for over 100 years, aggravated by irregularities in land acquisition and ownership by successive governments since independence.[66] For various reasons, the government through a presidential decree in 1968 categorized land in Lamu as government land.[67] More than 70 percent of Lamu residents, according to an official of the National Land Commission (NLC), are now regarded as squatters with no ownership documents for their ancestral land.[68] This has been a major point of contention among communities on the coast involved in land disputes and campaign for compensation for land acquired by government.

The land acquisition process has been fraught with irregularities, corruption and concerns of lack of adequate compensation for the residents from whom land has been taken.[69] Residents and activists recounted to researchers how, in the initial stages of LAPSSET, and especially with regard to the Lamu port, the authorities attempted to acquire land without compensating owners because, allegedly, the land belonged to government.[70]

Following community protest and legal actions, the authorities instituted a compensation process for Lamu port land, which included creating, in 2012, a committee comprising of both government and community representatives to verify those actually affected by the acquisition of at least 28,000 hectares (roughly 70,000 acres) for the Lamu port and thus eligible for compensation and also determine monetary compensation amounts.[71]

LAPSSET and other government officials claim that the compensation for those displaced by the Lamu port is being disbursed.[72] However, activists said that only a small fraction of those whose land was taken for the Lamu port have been compensated, and this is mainly because Kenyan authorities are reluctant to recognize them as legitimate owners of that land.[73]

The activists also attributed the compensation-related challenges to other factors. An official of Kililana Farmers Association said some government officials inflated the list of those to be compensated for land with additional names of those not known to own any land in the area. Some of the residents whose land was acquired said they never received compensation despite the records showing they had.[74] Residents in Manda Island and Kililana told researchers that the authorities had initially promised to pay KSh1.5 million ($15,000) per acre in compensation in 2013, but without any explanation the amount was later reduced to Ksh800,000 ($8,000), prompting complaints and agitation by community activists.[75]

In 2016, the Kenya government allocated a 975-acre piece of land to Amu Power to construct and operate the coal plant.[76] An official of Amu Power told researchers that compensation had yet to begin partly because of ongoing court cases and also because the authorities have yet to compensate residents for the land on which the plant will be built.[77] The NLC has completed verification of individuals whose land was acquired for Lamu coal plant and approved 514 names of people who will receive monetary compensation.[78]

The local officials in Lamu have sided with aggrieved residents over issues surrounding LAPSSET and associated projects. In October 2018, Lamu county government officials walked out of a meeting with a senior national government official in protest over irregularities in land acquisition and demanded compensation for all the land acquired for LAPSSET, not just a fraction of it.[79] The senior state official promised to ensure that all those whose land was acquired for LAPSSET are compensated.[80]

Mismanagement of land records at the national and county levels by state officials, the communal nature of land ownership among communities at the coast, and the difficulty in identifying legitimate land owners due to the lack of ownership documents for Lamu residents have further complicated land acquisition and compensation.[81]

II. Abuses Against Activists Working on LAPSSET and Associated Projects

Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders found that police and military officers in Lamu have broken up peaceful protests and outlawed public meetings by activists, arrested, detained, and prosecuted activists, sometimes unjustifiably, and accused activists of either having links or being sympathetic to Al-Shabab.[82]

Researchers documented at least 35 cases of individual activists who faced various abuses, either while protesting or simply because, according to the activists, they were known as activists on environmental issues. The whereabouts of at least two activists kidnapped by people believed to be police officers remain unknown.

In Lamu, researchers found that 11 of the 15 cases in which activists were arrested or summoned, authorities accused them of having links with terrorists. International and Kenyan human rights organizations, including the Nairobi based National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders, have monitored and regularly highlighted the harassment of activists at the coast.[83]

The Lamu activists are not alone. In Kenya, community leaders and rights activists who opposed evictions and exploitation by salt companies in salt mines in the coastal county of Malindi have faced threats, arrests and fabricated charges.[84] Environmental activists elsewhere in Kenya have also faced threats.[85]

Threats, harassment and violence against those opposing environmental and social harms from extractive and other polluting industries are also on the rise globally. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders has underlined the “unprecedented risks” faced by environmental human rights defenders globally, referring to the “growing number of attacks and murders of environmental defenders.”[86] In 2017, Front Line Defenders, an international organization that protects activists at risk, received reports on the murder of 312 defenders in 27 countries. Of those killed, “67 percent were engaged in the defense of land, environmental and indigenous peoples’ rights and nearly always in the context of mega projects, extractive industry and big business.”[87]

The experiences of Kenyan environmental activists at Lamu and elsewhere along the coast also highlight a troubling trend in which the local authorities are conflating peaceful civil society protests with abhorrent Al-Shabab attacks—whether out of genuine concern that there may be links or as a ruse to quash legitimate dissent. These abuses are part of a broader clampdown on civil society over the past five years in which the Kenyan government has attempted to severely limit foreign funding to civil society groups.[88]

As LAPSSET gets under way, authorities are likely to encounter more activism, not less. In addition to addressing the underlying grievances of the activists, the government should ensure respect for their basic rights of free expression, assembly and association.

Kidnapping of Two Activists

Two activists working on LAPSSET and land related issues in Lamu are missing after being kidnapped by people wearing police uniforms.[89] The two were among the 46-missing people on the coast documented by the Mombasa based rights group, Haki Africa.

In early 2016, activists Mohamed Avukame, 45, and Ali Bunu, 38, were separately kidnapped and have not been seen since.[90] Multiple interviewees said that, prior to their kidnapping, both Avukane and Bunu had reported threats on their lives by people who warned them against opposing state development projects.[91]

Avukame, a resident of Lamu’s Manda area and a land rights activist, was kidnapped outside the offices of Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI) in Mombasa where he had taken documents showing irregularities in acquisition and compensations for the LAPSSET land.[92] Relatives said that police have not investigated the kidnapping although both Avukame’s family and MUHURI officials say they reported the case at Nyali police station in Mombasa.[93] A relative said:

“We have searched everywhere for him. We have been to police stations many times and have even held discussions with the Director of Public Prosecutions. We have talked to press about his case, but still no hope in finding him.”[94]

Bunu, a resident of Pate island who was outspoken against the planned coal power plant and unsuccessfully resisted acquisition of his land by LAPSSET by continuing to farm the land despite government officials urging him to stop, was kidnapped near his home together with his son and brother.[95] Relatives who were with him believe he was killed and dumped in the forest, since they have been unable to trace the body despite a relative who witnessed Bunu being shot dead by the attackers.[96]

Arbitrary Arrests, Interrogations and Detentions

Researchers documented 13 cases of arbitrary detention and interrogations of activists by the police in Lamu between 2013 and 2018. The police arrested the activists either during peaceful protests or at their offices and held them in police detention centers.

In early 2013, police arrested and detained an activist, who was a father of six, for one day for convening open air meetings to educate villagers in Kizingitini about the environmental effects of LAPSSET projects such as the coal plant. “Police at Faza station warned me against criticizing government projects and later released me without charge,” said the activist.

In other instances, police accused activists of having links to Al-Shabab. This was especially common between 2013-2016, amid increased government surveillance and crackdowns on rights organizations and activists in regions with predominantly Muslim populations.[97] As one 32-year-old school teacher at the forefront of organizing community meetings on the environmental effects of LAPSSET told researchers from Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders:

“The government brands activists who speak against the project as terrorists. Police arrest, detain and even interrogate activists in a bid to intimidate them.”[98]

For example, a fisherman who actively campaigned for compensation by LAPSSET for expected disruptions to fishing, was arrested from Pate Island for alleged links with Al-Shabab in 2013, but he believes police arrested him because of his campaign against the anticipated adverse effects of LAPSSET to fishing, which is the economic mainstay of his community. He was detained for two days at Faza police station. The police released him without charge after one day.[99]

“Police interrogated me over what they said were my links with Al-Shabab but later warned me against criticizing government projects and instead to mind my own business”

In another example in late 2013, Abubakar Mohammed Khatib, 58, a staff of Save Lamu, was arrested at his house in Lamu Island and detained for three nights at Mpeketoni station, in Lamu west, shortly after sending a letter to the president expressing concern over LAPSSET.[100] Abubakar later died from acute asthma attack, which family and friends argued was caused by his detention in cold conditions. A relative of Abubakar Khatib said:

Police left him to sleep on cold cement floor for two nights without anything to cover himself and denied him food. They interrogated him over links with militants and tried to link him with Al-Shabaab, but later only charged him with incitement.[101]

In October 2015, in Ndau village, Pate Island, a 34-year-old activist advocating for public participation in LAPSSET decision-making said he was arrested by about 10 Criminal Investigations officers who took him to the sub-county commissioner’s office, where he was detained for a few hours. “Police then told me to stop opposing government projects because they were meant to benefit us,” he said.[102]

On April 15, 2015, police arrested a 45-year-old anti-LAPSSET activist from Lamu Island and detained him at Lamu and the nearby Mokowe police stations for seven days before releasing him without charge, according to the man’s lawyer.[103] Although the police said they had arrested the activist because of what they claimed were his links with Al-Shabab, their interrogation focused on his public campaigns against LAPSSET.[104] He was released after seven days without charge.

In at least 11 examples, police summoned activists for interrogation but did not detain them. A 34-year-old activist from Pate Island who is part of the campaign against the coal plant said he was arrested in 2015 by officers from the Directorate of Criminal Intelligence (DCI).[105] The officers, according to the activist, took him to Faza police station for interrogation. During the interrogation, the activist said, the officers questioned him on his work as an activist, the source of his funding, why he opposed to government projects and whether he supports Al-Shabab.[106] Police later that day released him without charge.

In early October 2015, over 10 officers from the DCI head office in Nairobi and Mpeketoni station raided Save Lamu, ransacking the offices and carting away files of key documents and summoned four staff to Nairobi for interrogation. [107] Police accused them of links to Al-Shabab and the series of terrorist attacks in Lamu that started with the one on the Mpeketoni shopping center on June 14, 2014. The Mpeketoni attacks killed at least 48 people and wounded several others.[108] A 32-year-old staff of Save Lamu recalled:

“We found police had printed statements from all our bank accounts and there was determination to try and link us to Al-Shabab and the attacks on Mpeketoni of mid-2014,” said the staff member.[109] Police returned the files eight months later and no one in the organization was charged with any offence.[110]

Police Harassment and Prosecutions of Activists

Researchers found at least 10 cases in which individual activists have faced prosecution for acts such as talking to the press and holding meetings with residents in which they demanded increased public participation, redress for environmental concerns, and adequate compensation for land taken for the various components of LAPSSET.

Researchers found that in each of the cases the police and military officials arrested and charged the activists with criminal offenses such as incitement, participating in an illegal assembly, trespassing on government land or resisting arrest.[111] While in some cases there may have been a basis for prosecution, it appeared from the circumstances that charges were designed to silence their protest actions. In most cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights defenders, the charges were dropped for lack of evidence, but often after suspects were detained for longer than the 24-hour period proscribed in Kenya’s constitution.

In early 2017, at least four Lamu activists were charged with trespass after they visited Lamu port to view progress on its construction; police later dropped all charges. In one instance, a 32-year-old activist on Lamu Island said he was arrested and locked up in a police cell within Lamu port for a few hours in mid-2017 and later charged with trespass, but the case was dropped before full trial for lack of evidence.[112]

In 2016, police teargassed and chased away a group of Save Lamu activists as they tried to access the LAPSSET site to see the progress of port construction, one 45-year-old activist who was part of the group told Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition for Human Rights. Three of the activists were charged with trespass.[113]

“When we went to court, the police who arrested us failed to turn up. We appeared in court thrice without police showing up and the case was dropped. They just wanted to harass or inconvenience us,”[114]

Researchers found that in other cases Kenyan police and military officers in Lamu broke up protests or meetings and arrested activists violently, kicking or beating them with sticks or gun butts, and later charged them with either incitement or trespass offences.

In one example in Kililana village, Lamu county, military officers beat and later detained a 47-year-old activist for allegedly trespassing onto the port property, but the activist told researchers that he was miles from the boundary of the Lamu port land at the time of his alleged offense.[115] He said police charged him with trespass, but the charges were dropped after the arresting military officers failed to appear in court.

In another incident in Pate Island in 2016, a 35-year old activist campaigning against logging by companies prospecting for oil and gas there, said that men in plainclothes who he believes were police officers beat him with sticks and gun butts while breaking up a meeting that campaigners were holding with the youth in the area to discuss the effects of oil and gas prospecting.[116] He said he was arrested and charged with incitement, but the charges were later dropped for lack of evidence before it even proceeded to trial.

In February 2014, a 48-year-old activist in Kililana who advocated for adequate compensation for land the state had taken from his community for LAPSSET, said he was arrested during a public meeting where he challenged officials from the National Land Commission on irregularities in the project’s land acquisition and compensation in Lamu. He said police accused him of being sympathetic to Al-Shabab, detained and interrogated him in three different police stations within Lamu county– Lamu Police station, Kyunga police station and Mpeketoni police station– for close to a week without taking him to court, and then charged him with incitement.[117] The incitement charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

In the above-mentioned example of a Save Lamu’s staff member, Abubakar Khatib, was arrested at his house in Lamu Island in 2013 a week after he signed a letter to the president objecting to the construction of the various components of LAPSSET without adequate consultations, an assessment of the environmental impacts and an agreement on compensation for the acquired land. Khatib was detained for several days, interrogated about links to Al-Shabab, and then finally released on charges of incitement. The family members who visited him in detention and helped free him alleged that he later died due to ill-treatment while in detention, including being made to sleep on cold concrete floor for two nights, thus aggravating his asthmatic condition.

Activists said the officials use arrests and detentions to pressure those with concerns over development projects to stop their activism– whether through public protests, public meetings or bringing lawsuits against government agents, or some other action.

Intimidation of Activists

Researchers from Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders found that, since the government started implementing its development projects in Lamu county in 2012, many activists who expressed concerns over the impact of the projects on the community received threats from local officials or unknown people. At least 30 activists said they have faced threats either in person or by phone.

In most cases, activists received warnings before they were later arrested or prosecuted.[118] Five of those interviewed said they became fearful and toned down their criticism of the development projects after receiving threats from police and other government officials such as chiefs and county commissioners.[119] Most of the activists persisted with their activism and were arrested or, in the two previously noted cases, kidnapped.

Two activists from Mokowe area– one, a 68-year-old land rights activist and another, a 27-year-old anti-LAPSSET and coal plant activist– said they first received anonymous phone threats in 2016 warning them against criticizing government projects.[120] Later that same year, they were summoned by an area chief who cautioned them against “fighting the government” by criticizing its projects, the 27-year-old recalled:[121]

“He told me that I was still young, and I should not ruin my life. He said I should first learn how government works otherwise I could be in for the shock of my life. He did not elaborate what he meant.[122]”

A female activist, 40, from Lamu Island said that since 2012 she has been advocating against the health and environmental effects of LAPSSET and urging the authorities to mitigate such effects.[123] In 2014, police entered her house at 2a.m. and told her they were searching for weapons. They did not find any, but harassed the occupants of the house, including guests. “This was an attempt to intimidate me, so I can stop talking about the environmental effects of LAPSSET, but they failed,” she said.[124]

Four activists told Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders researchers they have been blacklisted for government jobs as a result of their activism. The 40-year-old Lamu activist said both national and county government officials have blacklisted her for any state jobs. Three others also said they were blacklisted from state jobs. “The county government official openly told me that I cannot get a job in the same government that I criticize,” said the 34-year-old activist and resident of Lamu Island.[125]

Authorities have prevented activists from visiting sites or travelling outside the Lamu Archipelago. In one case, a 33-year-old man who campaigns on the environmental risks from the planned coal-fired plant said he can no longer travel freely outside his home because, on four occasions, police have arrested and forced him back to Lamu Island. On one occasion in 2016 when he attempted to fly to Nairobi, he missed his flight after police detained him at Manda airport for hours. He believes this is an attempt by the authorities to ensure he does not meet and talk with residents in other neighborhoods about the coal plant.[126]

III. Government Response

State Responses to Allegation of Abuses by Activists

Despite some activists reporting such cases of harassment and intimidation to police, police and government officials who talked to Human Rights Watch and the National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders either denied knowledge of such harassment or have failed to take any concrete steps to investigate the reports.[127] Perminus Kioi, the County Police commander, said:

“I don’t know why anyone would be arrested for talking about LAPSSET or coal power plant. We have never arrested anyone for talking about these issues. I have attended many parliamentary meetings and people talk freely. I am not aware of the case in which Save Lamu officials were summoned or were arrested,”[128]

Kioi urged activists who feel they are harassed or intimidated by police officers or other government officials to report the incident to the senior investigations commander in the area.[129] “If it is a genuine case, we will direct an inquiry file to be opened and then refer the file to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) for directions.” Other officials expressed open hostility toward civil society activists in general. A LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority official and a senior security official in Lamu said activists in Lamu lacked transparency and that their motives were not always clear.[130]

However, some activists told researchers they did not report the abuses to police because they did not believe police could investigate themselves, let alone hold their officers accountable.[131] They pointed out that there has been no investigation when cases were reported. The families of Ali Bunu and Mohammed Avukame, both men who have been missing after being separately kidnapped by people who families and witnesses believe were security officers, said they have reported the two cases to various police stations in Lamu but police have failed to investigate.[132]

Even though the independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) has existed for over six years and is meant to enable people to report police abuses to higher accountability institutions such as the IPOA to investigate violations by police, the activists said the authorities have failed to inform them of this possibility and therefore many said they were unaware of this option.[133]

In 2011, Kenyan parliament enacted a law to establish IPOA, a civilian police accountability institution, to investigate police violations. Over the last three years, IPOA has been overwhelmed by a rising number of cases amid budgetary cuts. Although it has made some progress in investigating some cases of police abuses in other parts of Kenya generally, the institution has yet to prosecute any police officer implicated in the many cases of police abuses in respect of politically sensitive circumstances, such as counter-terrorism or election-related violence. [134]

In view of the numerous cases of police abuses arising out of LAPSSET and associated projects in Lamu, Human Rights Watch and National Coalition for Human Rights Defenders urge the authorities to take the complaints by Lamu activists seriously and begin to hold the perpetrators to account.

IV. Kenya’s Legal Obligations

International and African Legal Obligations

Kenya has ratified several United Nations and African human rights treaties that protect rights applicable to the issues discussed in this report. The rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, as well the right to be an activist defending other rights, are universally protected under international conventions.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) protects the right to healthy natural environments as part of the right to health.[135] The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the committee of experts that monitors the implementation of the ICESCR, has stated that this requires states to take measures to ensure safe water and to prevent environmental pollution, including by third parties, such as mining companies.[136]

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, considered broadly reflective of customary international law, provides for rights to “freedom of opinion and expression” (article 19) and “peaceful assembly and association” (article 20).[137] It states further that the freedom of opinion and expression “includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”[138]

These rights are further elaborated in treaties such as the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Kenya is a state party.[139] Article 19 of the ICCPR obligates states to protect freedom of expression, only permitting governments to impose limitations or restrictions on freedom of expression if such restrictions are provided for by law and are necessary.[140] The ICCPR similarly provides for the right to peaceful assembly.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the independent body of experts that monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, in its General Comment No. 34 on the freedoms of opinion and expression, reaffirms these rights as indispensable and necessary.[141] Furthermore, states are obligated to ensure that persons are protected from any acts by private persons or entities that would impair the enjoyment of these freedoms.[142]

States parties should also investigate in a timely fashion attacks on persons exercising his or her right to freedom of opinion or expression, including arbitrary arrest, torture, threats to life and killing, prosecute perpetrators, and provide appropriate forms of redress to victims.[143]

The United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, while not a legally binding document, outlines principles enshrined in other legally binding conventions such as the ICCPR to support and protect human rights defenders in the context of their work.[144] The Declaration accords to human rights defenders the rights to meet or assemble peacefully (article 5a); to form, join and participate in non-governmental organizations, associations or groups (article 5b); and to study, discuss, form and hold opinions of all human rights and fundamental freedoms, and to draw public attention to these matters (article 6b).[145] It also requires states to conduct prompt and impartial investigations or ensure that an inquiry takes place whenever there is reasonable ground to believe that a violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms has occurred (article 9.5), and to take all necessary measures to ensure the protection of everyone against any violence, threats, retaliation, discrimination, pressure or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of exercise of rights (article 12.2).[146]

In addition, the special procedures created by the United Nations Human Rights Council have contributed to developing standards of protection specifically for environmental human rights defenders (EHRDs). The UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders has underlined the “unprecedented risks” faced by environmental human rights defenders, referring to the “growing number of attacks and murders of environmental defenders”.[147] The special rapporteur called on states to “reaffirm and recognize the role of environmental human rights defenders and respect, protect and fulfil their rights” as well as “ensure a preventive approach to the security of environmental human rights defenders by guaranteeing their meaningful participation in decision-making and by developing laws, policies, contracts and assessments by States and businesses [sic].”[148]

In March 2018, the special rapporteur on human rights and the environment presented to the Human Rights Council the synthesis of his work over the course of his mandate: a set of framework principles “to facilitate implementation of the human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment”.[149] Crucially, framework principle 4 calls upon states to “provide a safe and enabling environment in which individuals, groups and organs of society that work on human rights or environmental issues can operate free from threats, harassment, intimidation and violence.”[150]

Kenya is also a party to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR)[151], which sets out the rights to expression and opinion(article 9).[152] Articles 10 and 11 also provide for the rights to free association and assembly, subject to only necessary restrictions provided for by law.[153] The African Commission’s 2002 Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa establishes guiding norms guaranteeing the freedom of expression.[154] Article 4.2 states that “no one shall be subject to any sanction for releasing in good faith information on wrongdoing, or that which would disclose a serious threat to health, safety or the environment save where the imposition of sanctions serves a legitimate interest and is necessary in a democratic society.”[155] It states further that freedom of expression should not be restricted on public order or national security grounds unless there is a real risk of harm and there is a close link between the risk of harm and the expression.[156]

The African Charter also requires Kenya to respect the right that “All peoples shall have the right to a general satisfactory environment favorable to their development.”[157]

In 2017, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders made important observations with regard to business and human rights: that the responsibility of businesses to respect human rights not only entails a negative duty to refrain from violating the rights of others, but also a positive obligation to support a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders in the countries in which they are operating.[158] Discharging this duty requires consultation with defenders in order to understand the issues at stake and the shortcomings that impede their work. Business enterprises should assess the status of civic freedoms and the situation of defenders and engage with host States regarding their findings.[159] The reports notes a key element of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights is the requirement for companies to conduct human rights due diligence through which business enterprises may be able to identify whether they are involved in actual or potential adverse impacts on human rights and human rights defenders and in what ways.[160]

National Law

The 2010 constitution of Kenya guarantees the right to freedom of expression, which includes the freedom to seek, receive or impart information or ideas; freedom of artistic creativity; and academic freedom and freedom of scientific research.[161] The constitution limits the right to freedom of expression with respect to propaganda for war, incitement to violence, and advocating hatred on ethnic or other discriminatory grounds.[162]

The constitution also has very progressive provisions on freedoms of the right to picket, association, assembly and movement. The chapter on rights says, in part, that every person has the right to freedom of association, which includes the right to form, join or participate in the activities of an association of any kind.[163] It also provides for the right to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket, and to present petitions to public authorities peacefully.[164] It further provides for the right to freedom of movement,[165] and further outlaws discrimination on any grounds, including religion, community or race.[166]

Both the constitution and the National Police Service Act further protect the rights of an accused or arrested person, including the presumption of innocence. They outline clear procedures for those who have been violated that they can follow while seeking redress.

The National Police Service Act says, in part, that those who have been violated by police can file complaints against ill-treatment and the right to compensation for investigation by the Independent Policing Oversight Authority.[167] Once a complaint has been lodged, IPOA has the responsibility to investigate the alleged violation at the end of which it should forward the file to the office of the Director of Public prosecutions for either prosecution or further directions.[168]

The Kenyan constitution also has provisions on environmental protection. It provides that everyone has a right to clean and healthy environment.[169] It also allows any person who considers that the right to a clean and healthy environment has been violated, or even threatened with violation, to apply to court and request that appropriate action be taken to protect the environment.[170] The constitution outlines the environmental responsibilities of the State, including: ensuring the sustainable exploitation and conservation of the environment and natural resources; encouraging public participation on all environmental matters; and the utilization of natural resources and environment for the benefit of the Kenya people.[171]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Otsieno Namwaya, researcher, Africa Division, Human Rights Watch; Aditi Shetty, senior coordinator, Program Office, Human Rights Watch; and Salome Nduta, senior program officer at the National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders–Kenya. It was edited by Jehanne Henry, associate director in the Africa division at Human Rights Watch; Kamau Ngugi, executive director at the National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders–Kenya; Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor at Human Rights Watch; and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director at Human Rights Watch.

The following individuals also reviewed the report: Letta Tayler, senior researcher for terrorism and counterterrorism at Human Rights Watch, Juliana Nnoko–Mewanu, researcher on women and land, Women Rights Division at Human Rights Watch, Katharina Rall, researcher, Environment and Human Rights at Human Rights Watch, Komala Ramachandra, senior researcher in the Business and Human Rights division at Human Rights Watch, Yaqiu Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch and Joseph Amon, health and human rights consultant. Elvis Salano, a Nairobi intern, provided support with initial project planning and desk research.

Najma Abdi, Africa associate at Human Rights Watch, provided editorial and production assistance. Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, provided production assistance.

Human Rights Watch and National Coalition of human Rights Defenders would like to thank the environmental activists in Lamu and Nairobi, environmental experts and lawyers who shared their experiences and others such as government officials, police officers and the employees of private companies who helped in various ways by sharing information or identifying activists who have been victims of harassment and intimidation

Acronyms and Abbreviations

ACHPR African Charter on Human and People’s Rights.

DCI Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI), which until 2010 was known as the Criminal Investigations Department (CID).

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment.

ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment.

ICCPR International Convention on Civil and Political Rights.

IPOA Independent Policing Oversight Authority.

KDF Kenya Defense Force.

LAPSSET Lamu Port – South Sudan – Ethiopia Transport Corridor.

NEMA National Environment Management Authority.

ODPP Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions.

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.