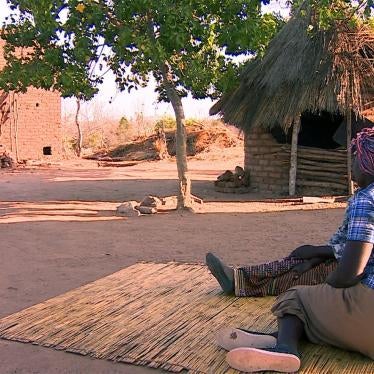

Deborah, a 58-year-old widow in Zimbabwe, said that after her husband died, her in-laws harassed and threatened her. They wanted her home and the land she had cultivated for four decades.

Deborah said her brother-in-law had “taken all of my fields and even tilled my yard [to plant crops] up to my doorstep. Now, he says that I cannot walk on ‘his’ fields. He says that I do not belong there. I reported this to the village headman, but he just tells us to live in peace.”

Land is a vital asset to individuals and communities around the world. But in many countries, laws and social norms put women and girls at a disadvantage when it comes to land inheritance, ownership, and control.

Men— male relatives, village heads, government officials, and others—hold most of the power over land.

The UN Commission on the Status of Women is examining issues affecting rural women and girls, including land rights and inheritance.

One of the draft meeting documents tells governments and others to take action. It urges reforms “to protect and promote the right of rural women and girls to land and land tenure security and ensure their equal access to and control over productive resources and assets, other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources and financial services and technology.” Such reforms are clearly needed.

Some countries’ laws directly condone discrimination against women and girls when it comes to land and property rights. In other cases, the problem isn’t the law, but rather practices and customs that favor men’s rights over women’s.

Women may have rights to use land, but in many contexts, these rights hinge on their relationship to a man: a husband, father, brother, or other male relative. If that man dies or becomes estranged, women may be forced off their land and out of their homes, with little or no recourse.

This was the case for the dozens of widows, including Deborah, whom Human Rights Watch interviewed for a report on Zimbabwe.

Widows said their in-laws threatened, physically intimidated, and insulted them. Some were forced out of their homes immediately after their husbands died. In other cases, in-laws turned up years after their husbands’ deaths demanding land and other property. In-laws commandeered widows’ productive assets like fields, livestock, and gardens, taking away their livelihoods.

Many widows told us that they lost everything.

Officials who should enforce laws meant to protect women’s property rights often fail to do their jobs. Several widows in Zimbabwe who fought back against property-grabbing told us that the courts sent all correspondence about hearings solely to male in-laws. In some cases, these men withheld the court notices to sabotage the proceedings.

Widows face such problems well beyond Zimbabwe. According to a recent World Bank report, “In 35 of the 173 economies covered by [the report], female surviving spouses do not have the same inheritance rights as their male counterparts.”

An important study of nine African countries told the stories of many women deprived of their inheritance. It explained how the HIV/AIDS pandemic only made disinheritance of widows worse, since many widows were blamed for allegedly infecting their husbands with the virus. It found that widows faced enormous barriers to seeking remedies through courts or traditional authorities, but managed to come up with creative initiatives to support one another, for example through organizing shelters and cooperative businesses.

Despite all the hardships, Deborah counts herself lucky. She managed to get help from a legal aid organization in Zimbabwe, the Legal Resources Foundation, which intervened to get a restraining order to stop the land grabbing. This organization, and many others, are working hard with scant resources and overwhelming demand to protect women’s rights. They are making a difference, but the problems remain vast.

Deborah still worries that her in-laws will try again to grab her land and home. As she put it, “I am fearful, and my heart is unsettled.”

Around the world, widows’ hearts will remain unsettled until their inheritance and property rights are secure.