(Nairobi) – South Sudanese authorities have failed to investigate the enforced disappearance in Nairobi of two South Sudanese men one year ago, and hold those responsible to account, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said today. Kenyan authorities should also step up their ongoing investigation into the enforced disappearances.

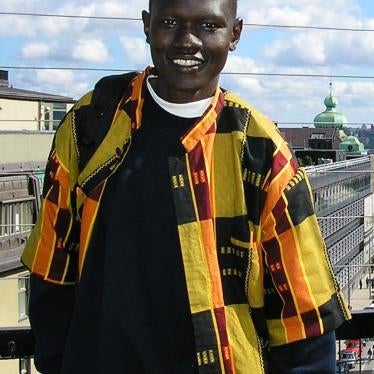

Dong Samuel Luak, a well-respected South Sudanese human rights lawyer and activist, and Aggrey Idri, a vocal government critic and member of the opposition, disappeared off the streets of Nairobi on January 23 and 24, 2017, respectively. They are believed to have been abducted by or at the request of South Sudanese officials.

“These two prominent men should not be allowed to simply vanish into thin air without a trace,” said Mausi Segun, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Responsibility for the safety of both men lies with both South Sudan and Kenya, yet neither is making a real effort to solve their disappearance.”

Opponents of the South Sudan government, real or perceived, have been targets of abuse and threats apparently from government sources, even when outside the country’s borders. Numerous activists and opposition members who fled South Sudan have reported threats and intimidation by suspected South Sudanese government agents in the region. Luak fled South Sudan in 2013, but continued to denounce human rights abuses and corruption after he moved to Nairobi in August 2013.

On January 27, 2017, a Kenyan court ruled that the men should not be deported, but by then both had been forcibly disappeared and presumably illegally transferred to Juba. In February 2017, nongovernmental organizations and family representatives filed a habeas corpus petition in a Kenyan court for the men’s release, but the court found on February 22 that there was insufficient evidence that they were ever in Kenyan custody. The judge ordered police to open a criminal investigation, which is ongoing.

South Sudanese authorities denied having custody of the men or knowledge of their whereabouts. However, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch received credible reports that the two men had been seen in custody at the National Security Services (NSS) headquarters in Juba on January 25 and 26, 2017, and were then removed from this facility on January 27. The two organizations believe they were transferred to another facility under the control of the South Sudanese government.

The forcible disappearance and return of the men to South Sudan, where they risk human rights violations, including torture and other ill-treatment, violates international law as well as regional and national Kenyan law. Enforced disappearances and torture are both crimes under international law in all circumstances and may be subject to prosecution as war crimes or crimes against humanity.

While Kenyan authorities have denied any involvement in or knowledge of the illegal actions, in recent years Kenya has allowed the deportation of several people with refugee status to their countries of origin. In November 2016, Kenyan authorities unlawfully deported James Gatdet Dak, a South Sudanese opposition member and spokesperson for the opposition leader Riek Machar, to South Sudan even though he had refugee status. He was held in solitary confinement at the NSS headquarters in Juba, then charged with treason and other crimes against the state in August 2017. On December 29, an opposition official, Marko Lokior Lochapo, was abducted from Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya.

Since South Sudan’s civil war began in December 2013, the NSS has arbitrarily detained dozens of perceived opponents, often torturing and ill-treating them with electric shocks, beatings, and harsh conditions. Authorities have also been responsible for enforced disappearances – in which authorities deny knowledge of a detention or abduction – as part of their campaign against those perceived to be government opponents.

On December 21, 2017, the South Sudan government and other opposition groups signed the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (CoHA) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in an effort to revitalize the 2015 Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan. As part of the new agreement, the government is required to release all political prisoners and detainees, prisoners of war and anyone deprived of their liberty for reasons related to the conflict and hand them over to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

“South Sudan should demonstrate it is serious about releasing political prisoners held unlawfully,” said Sarah Jackson. Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for East Africa, the Horn and the Great Lakes. “Both the South Sudanese and Kenyan authorities should urgently investigate and disclose the whereabouts and fates of the two men and ensure justice, truth and reparation for the crimes committed against them.”