These revelations are explosive. When did you first hear reports of this?

It was last December when we first heard about meetings in eastern Congo’s North Kivu province, where local leaders were discussing how former members of the M23 had been recruited to help protect President Kabila’s grip on power. At first, we didn’t know if this was anything more than a rumor. But then in January, we heard reports from credible sources in Goma, the main city in eastern Congo, that M23 fighters had been recruited from Uganda and Rwanda and sent to Congo to help protect the president and quash the planned protests. Our sources said they knew the M23 fighters and had seen some of them when they passed through Goma on their way to Kinshasa, the capital.

We felt it worth investigating, but knew we had to be careful: Soldiers who speak Kinyarwanda (the main language in Rwanda) are often accused of being M23 fighters even if they’re in fact Congolese who’ve been part of the army for many years and never joined the M23 rebellion. So we decided to go to Rwanda and Uganda, where most of the M23 fighters have been based since their abusive armed group was defeated in 2013.

How were you able to track down the former rebels to interview?

It wasn’t easy. We used a network of contacts who acted as scouts and facilitators. Through them, we were able to find former M23 fighters in military and refugee camps in Uganda and Rwanda who were willing to talk to us. Once we were alone in front of an M23 fighter, we would introduce ourselves and explain that we had nothing to give him, but we wanted the truth to be known. And we reassured everyone we interviewed that they could talk to us in confidence, and that we would not reveal their identity. That’s how we gained their trust. Over time, we were able to piece together how the M23 fighters were recruited and sent on different routes to Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, and Goma.

Back in Congo, we also found Congolese military officers who agreed to speak to us in confidence about how M23 fighters were integrated into their units.

Why did the M23 fighters say they agreed to participate in the operation?

Many told us they were tired of living in the camps and were grateful for the opportunity to return to Congo and get paid, after spending years abroad in often miserable conditions. Some said that they had been promised senior ranks and prestigious positions in the Congolese army. They were told that Kabila didn’t trust his regular army and needed the M23 who he could count on for their loyalty and ruthlessness in executing orders.

How were the fighters moved in secret across the borders to Congo?

They took different routes and traveled on different days to avoid drawing attention to their movements. Along the way, Ugandan, Rwandan, and Congolese officials, including army officers and border agents, facilitated their journeys, providing vehicles, flights, army uniforms, accommodation, food, and free passage.

What were M23 fighters told to do when they got to Congo?

They were told to use all available means to quash protests and protect the president, and make sure Kabila stayed in power. One fighter told us they “were deployed to wage a war against those who wanted to threaten Kabila’s hold on power.” They were given orders to shoot at every possible threat, or if a group of more than 10 people came toward them. Many fighters were told to fire at point-blank range. A lieutenant colonel in the Congolese army we interviewed told us that “the presence of soldiers has always frightened civilians,” and that Kabila deployed rebel fighters so that people who wanted to protest “would be too afraid to leave their homes.” An M23 fighter said that his recruiter told him: “The war won’t be hard; we will fight against demonstrators who have no weapons.”

What happened when the actual protests erupted?

On December 19, the last day of Kabila’s second and – according to the constitution – final term in office, security forces deployed heavily in cities and towns across the country. Groups of 10 or more people were warned that they would be dispersed by force. This appeared a deliberate attempt to keep demonstrators off the streets. There were “villes mortes” (general strikes, literally “dead cities”) across the country; shops and businesses were closed, and many people stayed indoors and kept their children home from school. Many of those who dared to protest were arrested.

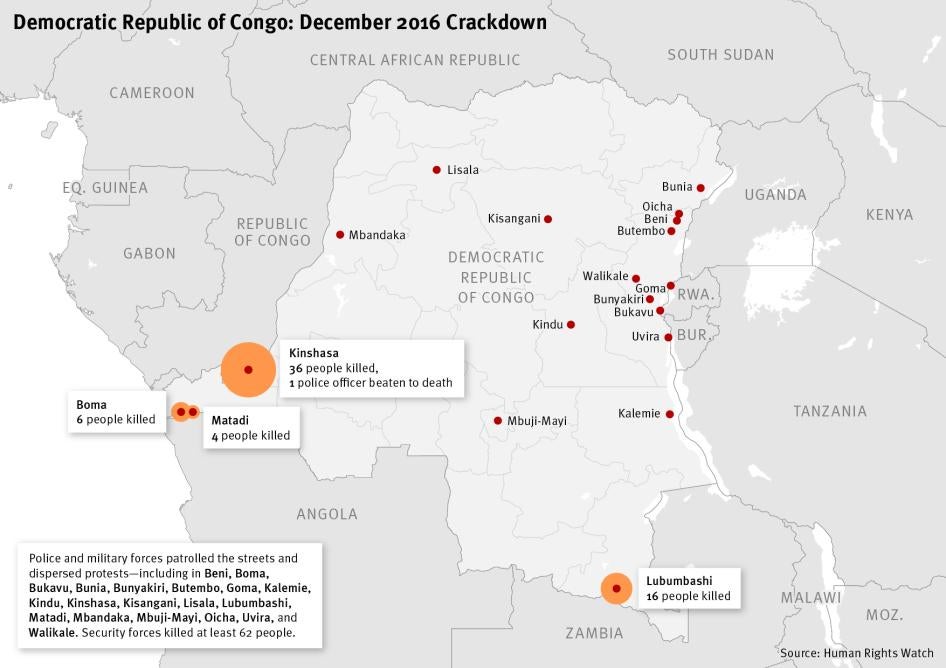

Then in the early hours of December 20 – once Kabila was no longer seen by many to be the “legitimate” president – more people took to the streets, blowing whistles, banging on pots and pans, and shouting that Kabila’s time in office was up. Security forces, including the M23 fighters integrated into their units, quickly sought to end the protests, killing at least 62 people over three days.

Security forces also arrested hundreds of protesters and even people just gathered outdoors in groups or wearing red – which had become a symbol of Kabila’s “red card,” a soccer reference telling him his time in power was over.

As one M23 fighter put it: “We imposed order in Kinshasa.” To make things worse, many relatives were denied access to hospitals and morgues, making it impossible for them to even bury their loved ones. Another M23 fighter said: “When there were bodies of people killed along the road, we picked them up quickly to hide them far away from where the international community would find out about them.”

What happened to the M23 fighters after the December protests?

Most fighters took part in the operation because they received promises of a happy life afterward. They were expecting to be able to leave the refugee camps and return home to Congo. But this didn’t happen.

The M23 fighters we spoke to all returned to Uganda and Rwanda soon after the protests, after it was clear that Kabila would now stay in power beyond the end of his constitutional limit. They said that some of their colleagues stayed behind though, integrated into units of the Congolese army, police, and Republican Guard, the presidential security detail. In May a new recruitment drive in the camps in Uganda and Rwanda began, with M23 fighters taken to Kisangani, in northern Congo, and told they would be prepared for “special missions” to respond to any new threats against Kabila.

What about people targeted during the crackdown, did any stories particularly touch you?

There’s the young taxi driver in Kinshasa who went outside to take a phone call in the early hours of December 20. Soldiers saw him talking on his phone, accused him of “calling rebels,” and arrested him. His family went to negotiate his release, but soldiers told them to return home and “cry over his death.” Shortly after, neighbors found his body in a hole next to the road, just meters from his home.

What do you think will happen now in Congo?

Despite the mounting pressure, Kabila has shown no sign he’s willing to step down or allow a peaceful, democratic transition. There have been calls for more demonstrations in the weeks ahead, and there’s a real risk of further violence.

This interview has been edited and condensed.