China’s new “super agency” to fight corruption is slated to start work in March 2018. However, the draft State Supervision Law establishing that body is not public, and what is known about the agency suggests the government and Chinese Communist Party are set to entrench an abusive system, not reform it.

The “super” agency will not only consolidate graft-fighting powers currently vested in various government departments, it also has new powers, including a detention procedure called "liuzhi" (留置). The agency is also empowered to investigate anyone exercising public authority – officials, managers in state-owned companies, and even public school managers. The agency will share space and personnel with the Central Commission on Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI), the powerful Communist Party body responsible for enforcing Party rules.

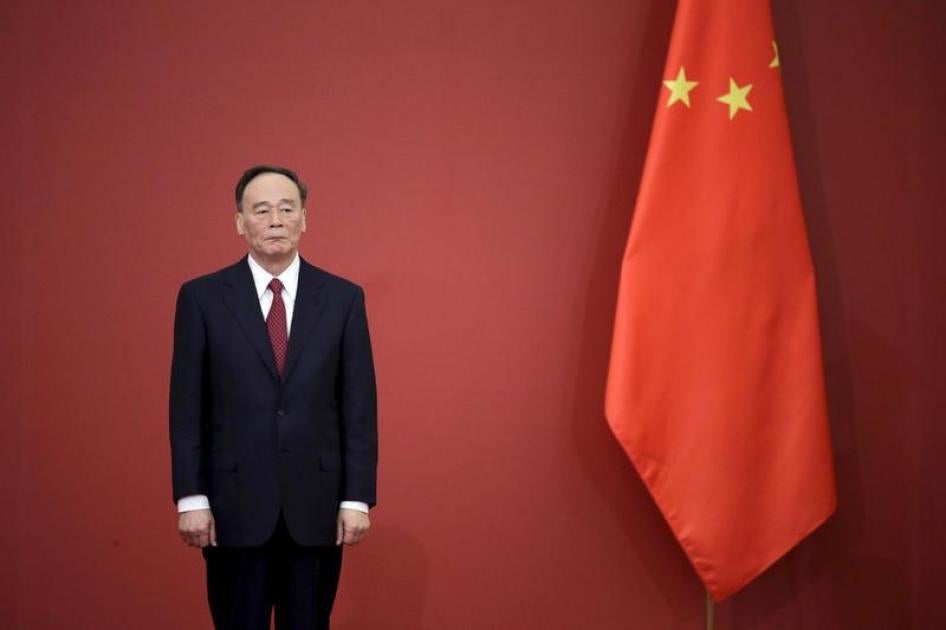

Scholars have speculated that liuzhi may have been designed to reduce the use of “shuanggui,” an extra-legal and abusive CCDI-run detention system imposed on Party members. Last December, Human Rights Watch published a report on shuanggui, detailing the use of arbitrary detention, torture and enforced disappearance, and called for its abolition. Around the same time, CCDI head Wang Qishan pledged to curb shuanggui abuses with steps such as videotaping interrogations.

Official articles suggest liuzhi will offer improvements: the system will be codified in law and subjected to stricter internal procedures; detainees will be given adequate food and rest; detentions will have time limits – three months, and, upon approval, another three months. But similar measures by the CCDI since the 1990s have not deterred abuses in the shuanggui system. There is no indication that those held under liuzhi will enjoy access to lawyers or redress mechanisms – two problems Human Rights Watch identified as facilitating serious human rights violations in shuanggui.

The available information suggests that liuzhi may simply be the legal, but no less abusive, twin of shuanggui – and no more likely to succeed in deterring corruption.

Wang Qishan, the CCDI chief tipped to head the super agency, has warned that “power without restraint is dangerous.” China’s top legislature should ensure that effective restraints, which can only be provided through fair trial protections for detainees, are included in a revised State Supervision Law.

|

Dispatches

China’s ‘Super’ Anti-Corruption Agency Set to Repeat Past Abuses

New Graft Watchdog May Legalize Wrongful Detention

Your tax deductible gift can help stop human rights violations and save lives around the world.

Region / Country

Most Viewed

-

March 9, 2026

Lebanon: Israel Unlawfully Using White Phosphorus

-

March 10, 2026

Haiti: Drone Strikes Put Residents at Risk

-

March 7, 2026

US/Israel: Investigate Iran School Attack as a War Crime

-

November 25, 2019

A Dirty Investment

-

July 25, 2017

“I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me”