For me, it all began with a pair of underpants.

A pair of dark-blue men’s underpants, hung up next to a pair of camouflage trousers on a clothes line strung across the courtyard of a school in Kasma village, India. This was the first thing I saw as I entered the school, but as I proceeded further into the courtyard, I noted other things that seemed out-of-place: empty beer bottles by the playground seesaw, a half-empty whiskey bottle in a classroom window.

The school’s principal, Agha Noor Ali—a tall man with thick spectacles—sat with me in his office and explained that for the previous four years, a small government paramilitary force had based itself inside two of the school’s 15 classrooms. They slept in the rooms and hung-out in the school when not conducting counter-insurgency operations against a guerrilla group active nearby.

Kasma Middle School is in a rural area where Ali already faced problems keeping his students in school. Children dropped out to work and support their impoverished families. Girls left to marry early. In response, the government had given the school money for 200 scholarships, to entice girls to come back to school.

But parents were unwilling to allow their adolescent daughters to return, despite the financial assistance, because they were afraid that the 10 armed men inside the school might sexually harass their daughters, or worse.

That’s when it hit home that here was a government with one arm trying its utmost to get children into school, while another arm of the same government was defeating that effort.

Around the world, schools come under attack by groups that want to put a stop to education or because they are soft targets for groups trying to undermine the government. The attacks on schoolchildren by the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and al-Shabab in Somalia are only the highest-profile examples.

But schools are also in danger when they are converted into military bases and barracks, detention and interrogation centers, and caches for weapons and ammunition, as they have in the past decades in at least 28 countries experiencing armed conflict. An armed force inside a school turns the school into a target for enemy attack. Schools are damaged or destroyed. In the worst cases, students and teachers have been injured and killed.

But even if the school is not a target for violence, the presence of troops undermines education. In India, following court challenges and intervention by activists, the government declared its intention to stop using schools as barracks. But in the years since I visited Kasma Middle School in 2009, I’ve investigated schools being used for military purposes in another seven countries experiencing armed conflict, across Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. In these countries, just the fear of such attacks leads students to drop out and lowers rates of new students enrolling or transitioning to higher levels of education.

This is a global problem in desperate need of a global response.

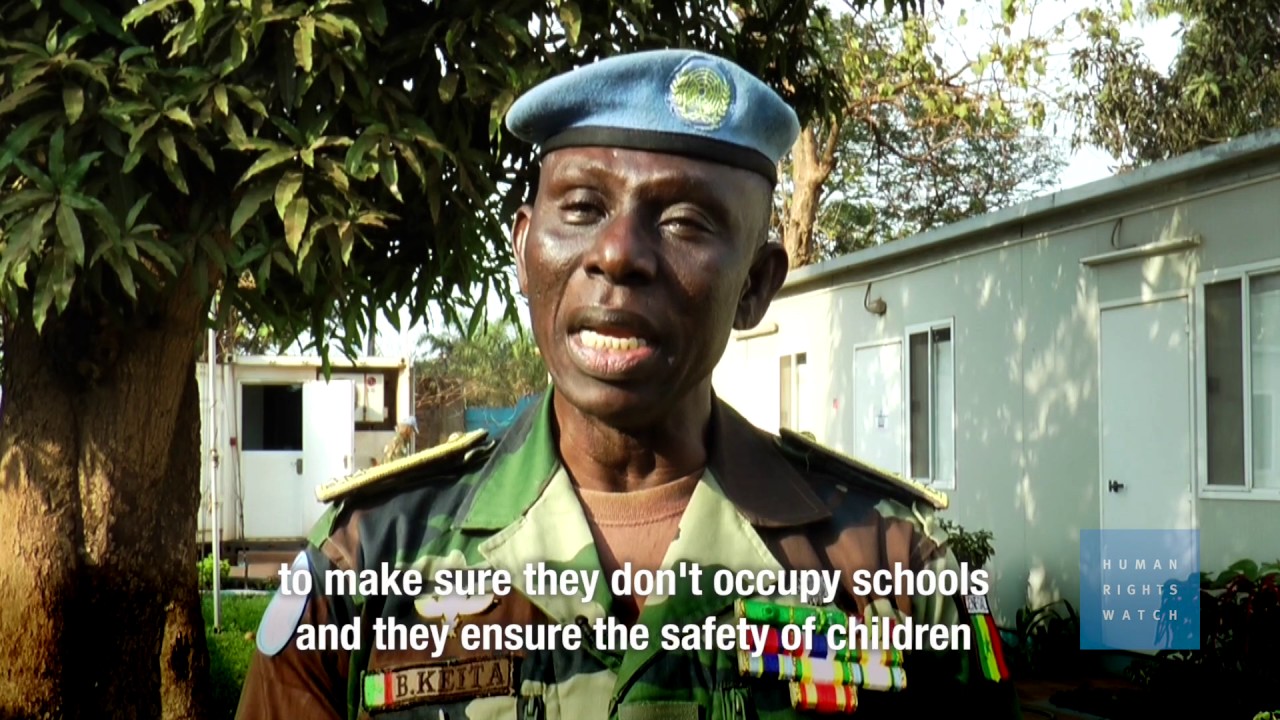

Increasingly, global consensus is solidifying around the “Safe Schools Declaration”—an international political commitment drafted in 2015 under the leadership of the governments of Norway and Argentina. The declaration lays out six common-sense actions that countries can take to respond better when schools are attacked, and to make it less likely that schools will be targeted. Chief among these recommendations is for militaries to refrain from using schools for military purposes.

From my research it’s clear that soldiers rarely take over a school wanting to interrupt children’s education. Usually they’re in search of a better vantage point, a school’s brick walls, a warmer place to sleep, or more comfortable latrines. So to change this practice, better advance logistics planning is needed to ensure that there are alternatives.

A greater understanding of the negative consequences for children’s safety and education is also required, so those factors can be appropriately weighed in military decision making. That’s why the Safe Schools Declaration encourages all armed forces to include explicit protections for schools in their training, doctrine, and planning.

As the fighting in Afghanistan enters its sixteenth year, and the war in Syria it’s sixth, it’s hard to imagine how these countries can ever rebuild, physically or economically, without an educated and skilled younger generation. But safe schools provide children in war zones with more than just an education. They also provide a space to meet and play with friends, and maintain a sense of normality and routine.

The Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense in Argentina are co-hosting a two-day international “Safe Schools” conference on March 28 and 29, highlighting how students, teachers, and schools are frequently, and deliberately, targeted in today’s wars.

So far, 59 countries have joined the Declaration, most recently France and Canada. This includes the majority of NATO member states, and also many countries currently or recently at war. At the conference in Argentina, more countries are expected to join. Amid all of today’s armed conflicts--all started by adults--we should do our utmost to ensure that children’s schools are left in safety and peace.