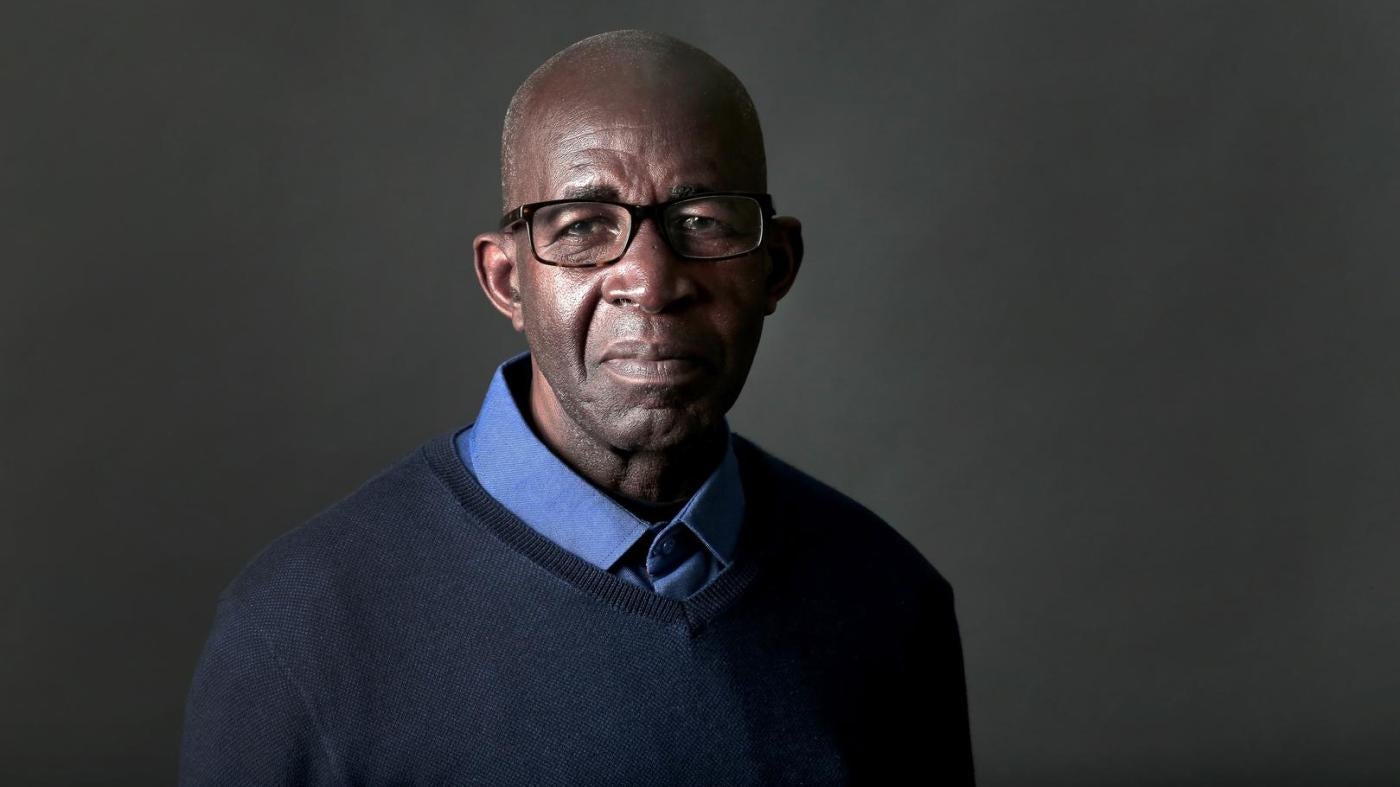

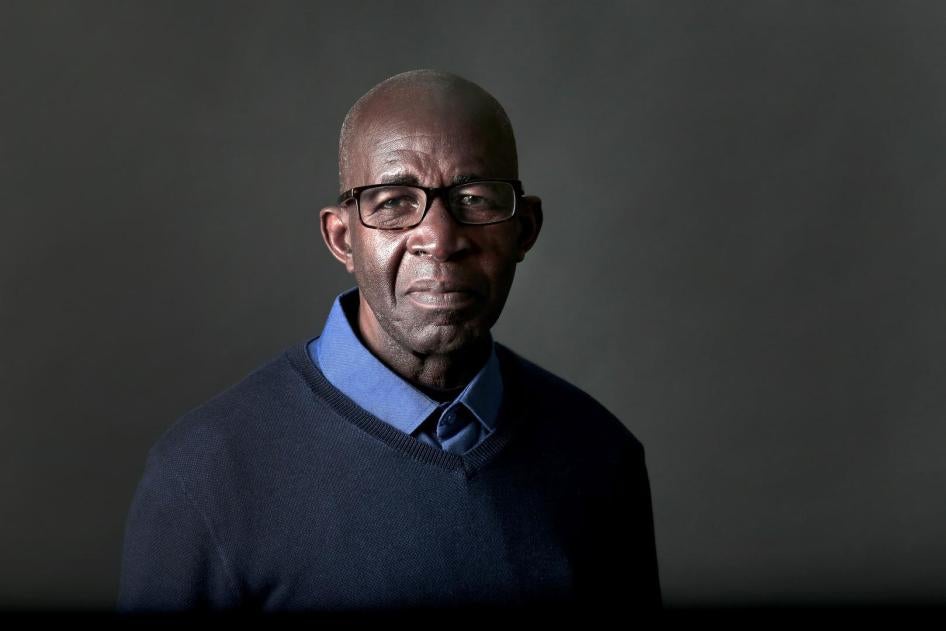

For the past year and a half, the Burundian government has brutally crushed any form of dissent. Since the crisis triggered by President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to run for a controversial third term began, hundreds of people have been killed and thousands arbitrarily imprisoned. Pierre Claver Mbonimpa is one of Burundi’s most prominent human rights activists and founder of the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (APRODH). In 2015, he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt, believed to have been by Burundi’s intelligence services. Pierre Claver, who now lives in Belgium, is the 2016 recipient of the Alison Des Forges Award for Extraordinary Activism. Human Rights Watch’s Benedicte Jeannerod spoke to him about the fear that has gripped his country, his life in exile, and his continued fight for the rights of all Burundians.

How do you view the human rights situation in your country, Burundi?

The human rights situation in Burundi is continuing to deteriorate in an alarming way. People are being killed every day, every month. There are hardly any civil society organizations or media left in the country. Activists and independent journalists are living in exile. Those who remain must work underground with the threat of repression.

Since Burundi recently broke off all relations with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and declared its experts persona non grata, there are no observers left. Acts of violence can take place without any outside witnesses. People are living in fear, there is no justice, and the crimes we have documented are not punished. Burundi’s recent withdrawal from the International Criminal Court took the country one step further down this spiral of violations and impunity.

What’s more, there is no longer any rule of law or any institution: the intelligence services, which are responsible for most of the crimes against the population and report directly to the president’s office, control the justice system and the police – which are supposed to provide security to the population.

My country has become a country of fear and violence, without any voices, without any respect for the law.

What is the nature of the violence taking place?

It is political violence, primarily targeted at members of opposition parties, people who don’t believe in Nkurunziza’s third term and people who took part in demonstrations.

The modus operandi has gradually changed. At the start of the crisis, dead bodies were found on the streets almost every day. Today, the killings are taking place more secretly: people are abducted in one province, killed in another, and buried without a trace. Families don’t know what has happened to their loved ones. This makes it very difficult to document these acts of violence.

The other type of violence is targeted at the families of people in exile. That is what happened to me. The government said even those who go into exile can’t escape us because their families are still here. In my case, this threat was realized. After the intelligence services tried to assassinate me in August 2015 and I was forced to go into exile in Belgium, my son-in-law, then my 24-year-old son were both killed.

Finally, the prisons in Burundi have never been as full as they are today. There are an estimated 10,000 prisoners. Even in 1998, when we were in the middle of a civil war, we didn’t reach that level. According to the information we have, more than half of these prisoners are detained for political reasons. They are accused of fictitious offenses of endangering state security or participation in the rebellion.

How can you keep working under these circumstances?

I live in exile in Belgium. The Burundian government closed my organization, the Association for the Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (APRODH). We are now working through a fragile network of focal points and volunteers who document violations as best they can, in a clandestine way. Our work has become extremely dangerous, not only for the people who work with us but also for those who give us information. The climate of fear is such that it has become very difficult to obtain information. That doesn’t stop us from having focal points, including in institutions like the police or in the prisons, among people who don’t agree with what the government is doing. We continue to publish reports, which we send to the international community as well as to the Burundian government. It’s essential to maintain attention and pressure on Burundi so that these crimes can’t be committed completely behind closed doors.

After everything that you and your family have been through, how do you find the strength to continue fighting?

What happened to me and to my family is what many Burundians are going through. In these particularly difficult moments, we must continue to fight and observe. Nkurunziza’s government is killing and terrorizing the population and could propel our country into civil war. This is not the moment to give up. If we abandon the human rights cause, then we will be abandoning the entire population to violence and to the absence of the rule of law. I will fight for peace and justice until my last breath.

What does the Alison Des Forges prize, which you received from Human Rights Watch, mean to you?

I have received other prizes for my work, but this is the one that means the most to me. Alison Des Forges was a friend. She used to visit me every time she came to Burundi and we would have long conversations on the human rights situation and on how to conduct investigations efficiently. Just one month before she died in a plane crash in the USA in 2009, we were together in Bujumbura. When I feel discouraged, I think of her and her strong commitment.

This interview has been edited and condensed.