On Monday, Turkey announced what could be a huge step forward for Syrian refugee children’s access to education – one that European leaders should strongly support. Volkan Bozkir, Turkey’s minister for European affairs, said that his country planned to start “giving Syrians in Turkey work permits.”

The promise was made in conjunction with Europe’s pledge to give Turkey three billion Euros and other perks in exchange for Turkey’s promise to reduce the flow of refugees to European shores.

The European Commission vice-president, Frans Timmermans, has grumbled that Europe was “far from being satisfied” with Turkey’s efforts so far, and asked Turkey to identify education “projects we can finance immediately so Syrian children can go to school.”

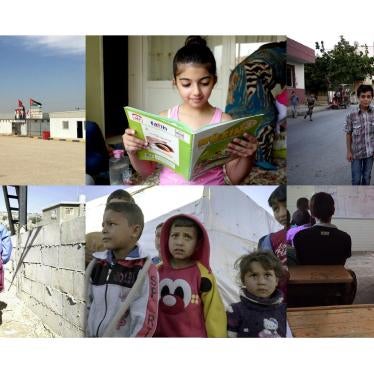

Syrian parents are desperate for their children to have a future. The UN refugee agency has identified lack of access to education as one of the “push factors” driving refugees’ travel to Europe. But of the 708,000 school-age Syrian children living in Turkey, only 212,000 were enrolled in formal education in 2014-2015.

Europe should be applauded for funding refugee children’s access to education, even if the motive is migration control. But research shows that what’s needed to get Syrian kids into school is for their parents to have the chance to support themselves.

Syrians forced to work illegally can’t earn a decent living and often need their children as breadwinners. Refugees’ low-paid, informal work helps drive Syrian child labor in Ankara, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). As Human Rights Watch documented, child labor is a key barrier to education for Syrian children in Turkey.

Mohammed, a 9-year-old in Izmir, Turkey, is a case in point. In his school in Syria, Mohammed said, “I was one of the best in my class, and I really liked learning how to read.” Now he works 11-hour days in a tailor shop with his father, who cannot support his family on his income, a fraction of his Turkish counterparts’ wages.

Employers in Turkey often pay Syrian refugees below-minimum wage, pressure them to work long hours in unsafe settings, and subject them to unreasonable pay deductions. Since they are working under the radar, they aren’t in a position to complain.

Turkey has pledged to provide work permits to Syrians before. An October 2014 regulation stated that the Council of Ministers was preparing to do so, and regional news media reported that the Labor and Interior ministries were developing relevant legislation. But politicians backtracked, worried that constituents’ jobs might be threatened. Last August, during the run-up to Turkish elections, the Labor Ministry announced that no work permits would be granted. Europe should help ensure that this time, Turkey follows through.

Turkey has taken some steps to boost refugee children’s access to education, like accrediting independent schools that teach a modified Syrian curriculum in Arabic. Indeed, Jordan and Lebanon – where the same vicious cycle of child labor and poverty is playing out -- should follow Turkey’s lead, especially by de-linking refugees’ ability to enroll in school from requirements for hard-to-get official residency permits.

Allowing adults to work won’t lift every barrier to Syrian children’s education, such as the lack of Turkish language classes and catch-up programs for refugee children who have missed years of school, and bullying by Turkish students. For these problems, European funding could also help.

But without protecting refugees’ right to work, it’s hard to imagine that simply funding charitable education projects will suffice. The average amount of time that refugees spend outside their home countries is 17 years. Leaving refugee kids to depend on notoriously fickle donor support for access to school is a recipe for failure.

ILO research shows that it makes good economic sense for host countries to protect refugees’ right to work – and that if they don’t, citizens and refugees alike will suffer. But that will be a tall political order in Turkey – with 10 percent unemployment – much less in Jordan and Lebanon, which are hosting even more Syrians as a proportion of their overall populations.

That’s why Europe needs to focus not just on funding short-term education initiatives, but on supporting host countries that agree to give refugees the chance to work and live in dignity. For many refugee families, work is a prerequisite to education, and education will be critical for children to contribute to Turkish communities, and to the future of Syria.