(Dakar) – Extortion by security forces at checkpoints remains an acute problem in Côte d’Ivoire four years after President Alassane Ouattara’s government promised to end it, Human Rights Watch said today. The Ivorian government should reinvigorate its efforts to fight checkpoint extortion, which undermines the freedom of movement and property rights of drivers and residents in Côte d’Ivoire.

In May 2015, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 80 people in Abidjan, the country’s economic capital, and western Côte d’Ivoire, including drivers, market vendors, farmers, community leaders, local officials, and members of the security forces. The vast majority of those interviewed said that extortion has decreased in Abidjan and the major roads traveled by foreign businessmen and investors, but remains pervasive on secondary roads in rural areas. The problem is particularly acute in the north, where Human Rights Watch conducted research in October 2014, and in the west, which has a relatively high concentration of security forces given the risks from cross-border incursions and criminality.

“While there has been some progress over the last few years, President Ouattara’s government hasn’t done enough to end checkpoint extortion,” said Jim Wormington, West Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Security forces continue to enrich themselves at the expense of ordinary Ivorians, many of whom are already struggling to earn enough to make ends meet.”

After assuming office following the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Ouattara’s government took some positive steps to tackle extortion. The government published an inter-ministerial order with a list of 33 authorized checkpoint locations nationwide and began to dismantle illegal roadblocks on major roads between the country’s larger cities. A specialized anti-racket unit was also set up to investigate abuses.

These initiatives have had limited impact. There have been scant investigations of higher-level officers implicated in extortion and a failure to consistently prosecute cases involving low-ranking security forces. A World Bank-funded 2014 study by the National Higher Institute of Statistics and Applied Economics estimated the total annual cost of extortion on roads to Côte d’Ivoire’s economy as 340.5 billion CFA (US$567 million) – an extraordinary amount, although less than the 369.6 billion CFA (US$616 million) the same institution said was lost to extortion in 2012.

Much of the extortion Human Rights Watch documented in western Côte d’Ivoire on roads around Duékoué, Guiglo, and Bloléquin occurred at unauthorized checkpoints staffed by police, gendarmes and soldiers. The extortion appears to be well organized. Drivers transporting passengers in taxis and on mototaxis (motorbikes) pay a daily set fee, usually 500 to 1,000 CFA (US$1-2), at each checkpoint, and officials track each driver’s registration number to determine whether the person has paid. Drivers said that if they refuse to pay, the security forces find an excuse to temporarily detain them, sometimes for hours on end. A taxi driver in Guiglo told Human Rights Watch: “If you don’t pay, it’s a fight. If you don’t give him his share, it’s a fight.”

Security forces usually only demand payment from passengers if they are transporting commercial goods, such as when villagers take produce to weekly markets. However, immigrants from neighboring countries are often singled out for extortion even when traveling as passengers on mototaxis, taxis, or gbaka (minibuses).

Community leaders told Human Rights Watch that immigrants from Burkina Faso are particularly targeted in and around Bloléquin, where security forces often confiscate residency papers and demand up to 3,000 CFA (US$6) for their return, wrongfully claiming that the papers are not valid because they were obtained in another locality. Members of the security forces unlawfully detain those who refuse or fail to pay. Two years after Human Rights Watch first documented this practice, little seems to have changed.

Since its creation in 2011, the anti-racket unit’s work has been undermined by inconsistent financial support from the Ivorian government and the failure of security force commanders to discipline violators or to refer them for prosecution.

Indeed, multiple sources told Human Rights Watch that officers and even their superiors often take a cut of the money collected at checkpoints. The reluctance of subordinates to inform on their superiors means that officers are very rarely investigated and prosecuted. The military tribunal, which under Ivorian law has jurisdiction over police, gendarmes, and soldiers, had by July 2015 in any case failed to adjudicate any of the cases referred to it by the anti-racket unit in 2015.

While law enforcement officials in western Côte d’Ivoire contend that an increased security presence on roads is necessary to fight banditry, that is no excuse for extortion, Human Rights Watch said. Extortion is illegal under Ivorian law and violates the right to freedom of movement under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the right to property under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

“Rather than offering protection, security forces are abusing their position by preying on the very people they are supposed to protect,” Wormington said. “If the Ivorian government is serious about ending checkpoint extortion, it should strengthen the capacity of the anti-racket unit and the civilian and military justice systems to investigate and prosecute violators.”

Extortion of Drivers in Western Côte d’Ivoire

Members of the security forces openly extort money from drivers of mototaxis and taxis on both primary and particularly secondary roads in western Côte d’Ivoire. Human Rights Watch repeatedly saw vehicles held up at checkpoints and drivers negotiating with the security forces to let them pass.

Much of the extortion documented by Human Rights Watch occurred at checkpoints not included in the 2011 inter-ministerial order, which lists authorized checkpoints. Checkpoints at the entrances to towns were often staffed by police and gendarmes, while gendarmes and soldiers frequently operated checkpoints between towns and on secondary roads. Other checkpoints on secondary, unpaved roads were staffed exclusively by soldiers. Drivers and residents said that customs and forestry officials were present at some checkpoints, and also demanded illicit payments if a passenger was transporting imported goods or agricultural produce.

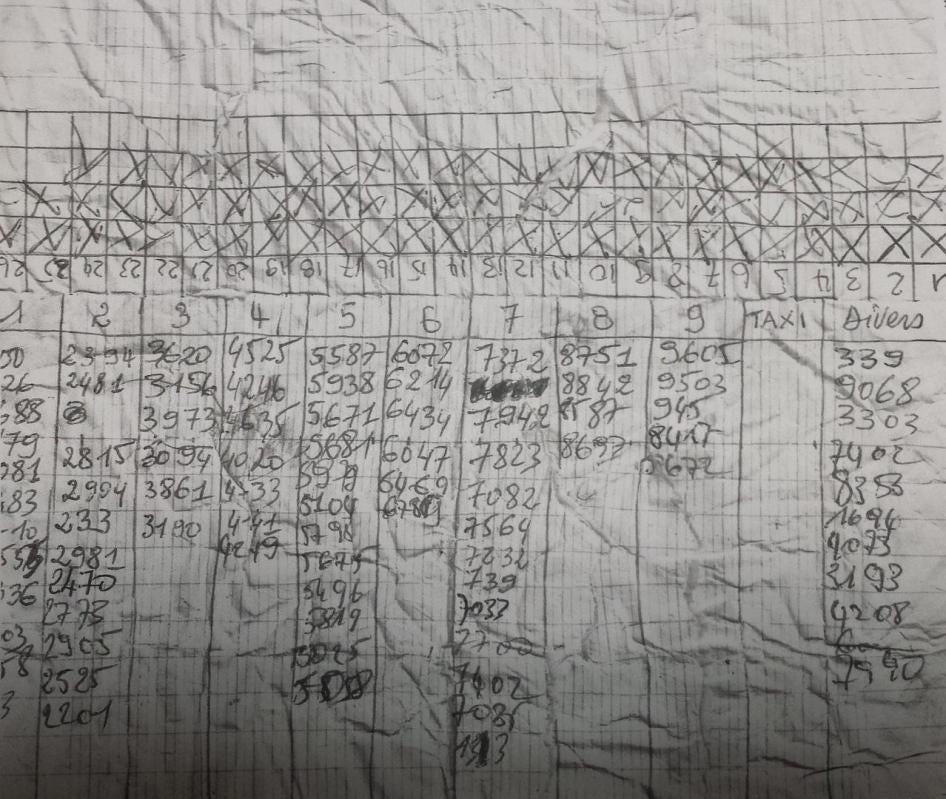

The extortion that occurs at checkpoints appears to be well organized. Mototaxi and taxi drivers told Human Rights Watch that they pay a daily set fee, usually 500 to 1,000 CFA (US$1-2), at each checkpoint. When the driver pays, the officials at the checkpoint record the vehicle’s registration number so that, if the driver comes back that day, the officials know he has already paid. At some checkpoints, a new payment is due when the security forces change shifts in the evening. An Ivorian official showed Human Rights Watch a copy of a table that security forces used at a checkpoint in Daloa to keep track of the registration numbers of vehicles passing through. A mototaxi driver working in a village near Bloléquin explained the system:

In order to be accredited as a mototaxi driver by the authorities in Bloléquin, each driver pays 10,000 CFA to the gendarmerie to get a number plate. The first journey of the day, the security forces write down your number, so they know that you have paid for the day. On the way to Bloléquin, for example, we pay 1,000 CFA – we give the money to the gendarmes each day, but I think they also share it with the FRCI (Republican Forces of Côte d'Ivoire (Forces Républicaines de Côte d'Ivoire)).

Taxi and mototaxi drivers frequently admitted that one reason they were obliged to pay at checkpoints was that they do not have a valid driver’s license, insurance, or taxi and vehicle inspection certificates. Interviewees said that obtaining these documents could be a lengthy bureaucratic process, and frequently required payment of a bribe. A key goal of the anti-racket unit has been to try to convince drivers to obtain these documents and to work with local government agencies to streamline the processes for doing so.

Other drivers said that even when they had the right papers, they were still forced to pay. One community leader from a village near Duékoué told Human Rights Watch that the security forces at checkpoints tell him, “We can’t eat your documents,” and force him to pay anyway. The head of the anti-racket unit, Commissioner Alain Oura, told Human Rights Watch that this discourages people from getting their papers in order: “If drivers know that they’ll be obliged to pay even if they have the correct paperwork, why would they think it worth getting their licenses?”

Human Rights Watch research was conducted in and around Daloa, Duékoué, Guiglo, and Bloléquin, but other organizations have documented similar extortion elsewhere in western Côte d’Ivoire. An October 2014 United Nations Group of Experts report observed that unauthorized checkpoints are particularly present in southwestern Côte d’Ivoire. Drivers of passenger buses who travel frequently in the southwest told Human Rights Watch that the road from Guiglo to Tai is particularly problematic, with more than 10 checkpoints along an 85 kilometer stretch of road.

Impact on Livelihoods

Community leaders told Human Rights Watch that mototaxi drivers provide vital revenue to villages in a region that was hard hit by the 2010-11 post-election crisis. “We need our boys to run the mototaxi services in order to survive,” one elderly woman said. Drivers described paying at checkpoints as unavoidable if they want to make enough trips each day to make a living. The head of a mototaxi cooperative said that once the fees paid at checkpoints are deducted, a driver might bring home 5,000-6,000 CFA per day (US$10-12), from which he still has to contribute to the cost and maintenance of his vehicle.

Security forces also often demand payment from passengers in taxis or mototaxis if they are transporting commercial goods, such as when villagers take produce to weekly markets or when farmers transport cocoa from fields to local buyers. One community leader told Human Rights Watch that farmers in his village have to pay 500 CFA (US$1) each time they pass a checkpoint that leads to their cocoa fields, a journey they make almost every day. Another woman said that she pays forestry officials at a checkpoint near her village 1,000-1,500 CFA (US$2-3) per sack of produce every time she takes goods to the market in Bloléquin.

Checkpoint extortion, through the arbitrary seizure of money and other property, violates people’s right to property under article 14 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights. Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights also provides Ivorians with the right to food and to an adequate standard of living. Although the general obligations on a country are to progressively realize these rights, countries are obliged to not negatively impact people’s right to an adequate standard of living. The arbitrary seizure of money and other property by security forces at checkpoints in Côte d’Ivoire arguably constitutes a breach of these obligations.

Targeting Immigrants from Neighboring Countries

Drivers and residents told Human Rights Watch that immigrants from neighboring countries are especially targeted for extortion. When a vehicle is stopped at a checkpoint, the security forces generally ask to see the identity papers of those on board. When immigrants from neighboring countries travel without valid papers, the security forces demand unofficial payments of 1,000-3,000 CFA (US$2-6). If the traveler is in a taxi or minibus, they often make the driver, and all his passengers, wait until the fee has been paid. A community leader from a village between Toulépleu and Bloléquin described the impact on freedom of movement:

There are too many checkpoints here, it really grates on us. At each roadblock, they ask for the papers of the people in taxis. Everyone has to have their papers, or the vehicle will be blocked. You can end up staying there for a lot of time – more than two or three hours.

The security forces, especially in the area around Bloléquin, often target immigrants from Burkina Faso, known as Burkinabés, for extortion, even when they are traveling with valid identity papers. In addition to an identity card, security forces ask Burkinabés to produce a residency certificate (certificat de résidence), a document issued by the Ivorian administration that confirms residency in Côte d’Ivoire. If a traveler presents a certificate that was issued in a locality other than Bloléquin, the security forces often say that it is not valid and demand payment in exchange for the return of document.

Because many Burkinabés from other parts of Côte d’Ivoire have moved to Bloléquin to work on cocoa, coffee, or rubber plantations, many have residency cards from other districts. A Burkinabé community leader from a village near Bloléquin said:

If you have a card that wasn’t issued here in Bloléquin, for example if you moved from San Pedro or Daloa, they’ll say to you, “You live here, but your card wasn’t issued in this area.” And then you’ll have to pay 2,000 CFA or 3,000 CFA (US$4 or $6) to get your card back. They don’t do that to everyone, just for us, the Burkinabés. If you don’t have money to pay, you have to wait, they don’t let you go. You have to ask your cousin to come with the money in order to free you.

Burkinabés also encounter problems when they travel to Bloléquin from other towns in the area to do business or visit family. A Burkinabé from a village near Guiglo described what happened when he visited cousins in Bloléquin:

I was in Bloléquin, but I got my card in Guiglo, and so the gendarmes and FRCI told me it wasn’t valid there, and I had to pay. They’ll do anything to get money. If you don’t pay, you’ll stay, next to the checkpoint. They’ll make you wait.

An official in the anti-racket unit told Human Rights Watch that a residency certificate is valid no matter where it is issued in Côte d’Ivoire. Indeed, provided they can produce an identity card, travelers should not be required to show their residency certificate.

Burkinabé community leaders described checkpoint extortion, as well as conflicts over land, as the two biggest problems their community faces. One community leader said that extortion demands are sometimes accompanied by xenophobic remarks, such as, “go back where you came from.” The targeting of Burkinabés for extortion amounts to discrimination on the basis of nationality or citizenship affecting the right to freedom of movement within a country and the right to property under international law, including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Security Risks are No Excuse for Extortion

When asked about checkpoint extortion, senior FRCI and gendarmes acknowledged that it can be a problem but said that an increased security presence in western Côte d’Ivoire is necessary to address cross-border incursions and criminality, particularly attacks on buses and private vehicles by heavily armed bandits.

One FRCI commander admitted that he had ordered the construction of all the checkpoints in the area he oversees, even those not authorized by the 2011 order. He showed Human Rights Watch a map on his wall with pins marking the location of checkpoints and explained: “The checkpoints that are in the bush, I put them there. I put them in places where there is a lot of banditry. They’re there because there are too many robberies in this area.”

In October 2014, Human Rights Watch documented violent attacks on roads in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Although the problem appears to be less pronounced in the west, it remains a real threat. A taxi driver told Human Rights Watch he was shot in the back and his car was sprayed with gunfire as he fled bandits in January 2015. Another villager described being ambushed by masked men with Kalashnikovs and forced to lie on the floor while attackers stole her money and goods. Several community leaders told Human Rights Watch that they believed that the addition of checkpoints had improved security on unpaved roads near their villages.

However, even if security threats do justify a heavier presence of FRCI and gendarmes in western Côte d’Ivoire, that is no excuse for extortion. Community leaders told Human Rights Watch that checkpoint extortion in fact can contribute to insecurity by furthering distrust between the population and the security forces.

Several residents said they believed that checkpoints were really just an excuse for extortion. The chief of a taxi depot told Human Rights Watch: “It’s not for our security, it’s against us.” A Burkinabé leader from a village near Guiglo shared this view, saying, “They say that it’s for our security, but ultimately it’s for extortion.”

The erection of checkpoints not listed in the 2011 order violates the right to liberty of movement under article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires any restriction on freedom of movement to be authorized by national law. Even at checkpoints authorized by law, stopping drivers to extort money constitutes an illegitimate restriction on freedom of movement.

Inconsistent Support for the Anti-Racket Unit

Côte d’Ivoire’s anti-racket unit, composed of police, gendarmes, and members of the military, is mandated to investigate incidents of extortion as well as to train law enforcement to conduct security checks on roads without violating drivers’ rights. The anti-racket unit also partners with the Traffic Flow Observatory (l’Observatoire de la Fluidité des Transports), a government watchdog, to identify illegal checkpoints and dismantle them.

The anti-racket unit uncovers extortion by planting undercover agents in public transport vehicles. They report security forces who demand money to their superiors, who are expected to take disciplinary action. The anti-racket unit also refers cases to the military tribunal, which has responsibility for prosecuting extortion involving police, gendarmes, and military, and the civilian courts, which has jurisdiction over customs and forestry officers.

Since its creation in 2011, however, the unit’s effectiveness has been limited by inconsistent financial support from the Ivorian government. In May 2013, the government’s failure to give the unit an operational budget forced it to stop the bulk of its activities, including a hotline that Ivorians could call to report extortion. Although funds were restored in October 2014, the funding gap affected the unit’s reputation among road users and its capacity to deter security forces involved in extortion, who an official in the anti-racket unit said are, “advocating for the death of our unit.”

One driver told Human Rights Watch that, when he tried to report an incident to the unit’s anti-racket hotline in June 2014, the line was dead: “I tried to call the anti-racket unit number multiple times. I was at the northern checkpoint at the exit of Yamoussoukro, and the gendarmes were asking for money. I tried calling but there was no answer.” The hotline was reopened in late 2014.

Limited funds have also meant that, for the bulk of its existence, the majority of the anti-racket unit’s activities have been in and around Abidjan. In late 2014, the unit began working in three pilot locations in the interior – Daloa, Bouaké, and San Pedro – and with more funding, the unit’s commander says he would like to expand activities to other areas.

A “Subculture” of Extortion in the Security Forces

Inevitably, given the limited resources of the anti-racket unit, primary responsibility for preventing extortion falls on the hierarchy of the security forces, as part of their general responsibility for ensuring discipline.

Cases usually only reach disciplinary proceedings, though, if field-level officers refer subordinates allegedly implicated in extortion to their superiors. But the anti-racket unit says this rarely happens. Instead, an anti-racket official said, officers deal with the cases informally, often without any official punishment:

Commanders need to be ready to sanction their subordinates. We send reports of extortion cases to the head of each unit, but there’s no follow up. It’s only if there’s a sanction that we feel like we’ve had an impact.

The lack of consequences reflects, at the very least, a failure among officers to take extortion seriously. A 2014 World Bank-funded study found that the root causes of the problem can be traced to a “subculture” “embedded” in the security forces, in which extortion “is perceived as normal.” It may however also be symptomatic of a system in which officers, and even their superiors, benefit directly from extortion.

Multiple sources, including within the security forces, told Human Rights Watch that security forces assigned to a checkpoint must often give a fixed amount of their takings to their superiors, who in turn pass on a share of the spoils up the chain of the command. An officer in the anti-racket unit told Human Rights Watch that this practice, known as handing in “a good financial report,” remains one of the biggest obstacles to eliminating extortion.

The Role of Ex-Combatants

Within the military, commanders in the past sought to justify their failure to punish extortion by saying that the majority of soldiers at unlawful checkpoints are supplementary, volunteer fighters who fought alongside the Republican Forces during the post-election crisis but who have not subsequently been integrated into the military. An official in the anti-racket unit said that because these former combatants do not get any government wage, but remain in and around military camps, commanders would tell them, “go and find your salary,” and would turn a blind eye to their extortion. As volunteer fighters are not part of the military chain of command, they could also not be officially disciplined, for example through docked wages.

The end of Côte d’Ivoire’s Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) process means that commanders should not be able to keep offering this flawed excuse. The Ivorian government established a June 30, 2015 deadline for former combatants to enter the demobilization process, which gives them access to vocational training and financial assistance in exchange for turning in their weapons and making a commitment to return to civilian life. The military leadership instructed all commanders to transfer non-integrated fighters to the demobilization authority by June 30. A UN official described the potential impact that this could have on extortion:

It’s only now that many of the non-integrated ex-combatants in the FRCI will go through the DDR process. The end of the DDR process is the end of the excuses for the FRCI – a professional army shouldn’t have the need to resort to extortion. That’s only a theory, though, there’s of course still gendarmes and FRCI who might continue with extortion. The real question is, “Are the FRCI really going to cut the umbilical cord to extortion?”

Prosecuting Extortion

Ultimately, deterring checkpoint extortion will require criminal sanctions against violators, particularly commanders and officers who are implicated. The military justice system, however, which has jurisdiction over the army, police, and gendarmes, is severely under-resourced, with only one military tribunal in Abidjan for the whole country. The tribunal, which is focusing on cases related to the post-election crisis, had by July failed to adjudicate any of the dozens of extortion cases the anti-racket unit had referred to it in 2015.

Furthermore, several legal experts said there was a need for comprehensive reform of the military justice system. They cited in particular the need to address the tribunal’s lack of independence from the ministers of interior and defense, who must give permission before a prosecution or trial can begin.

The military tribunal’s jurisdiction is also currently too broad. Under the Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa, issued by the African Commission on Human & Peoples’ Rights, the jurisdiction of military courts should be limited to military personnel and to strictly military issues and should not extend to the police.

In the absence of comprehensive reform of the military justice system, and given the limited resources of the anti-racket unit and military tribunal, they should consider targeting their investigations and prosecutions against those most responsible for extortion, particularly high and mid-ranking commanders. The head of the military tribunal, Commissioner Ange Kessy, told Human Rights Watch that commanders implicated in extortion would be prosecuted: “Commanders will be tried if their agents commit extortion. It’s not possible that they don’t know what their troops are doing. A good leader knows what his troops are doing.”

So far, however, the anti-racket unit has not had success in convincing those caught at checkpoints to inform on their superiors, with an officer in the anti-racket unit saying, “the racketeers we catch will never implicate anyone higher.” The officer attributes this to “a climate of impunity,” in which, “agents think that, even if they say something, their leaders will never be punished.” The anti-racket unit is instead compiling reports on commanders who repeatedly fail to sanction instances of extortion within their units, and hopes that this will ultimately result in disciplinary action against those commanders.

Recommendations

- To the Prime Minister’s Office and Ministries of Interior and Defense:

-

Ensure transparent investigations of – and where evidence emerges, disciplinary measures against – commanders in areas in which checkpoint extortion is widespread for their failure to investigate and punish troops involved in extortion;

-

In conjunction with the anti-racket unit, circulate and make public guidance to police, gendarmes, and FRCI officers on the conditions that must be fulfilled for checkpoints set up for security purposes to be legal under Ivorian law;

-

Increase the resources of the anti-racket unit to enable it to develop a larger presence in western Côte d’Ivoire, including through monthly missions to Bloléquin, Guiglo, and Tai, as well as other areas of the country in which extortion is pervasive;

-

Make clear that funding for the anti-racket unit, at an increased level, is secure for a minimum of five years;

-

Prioritize a comprehensive reform of the military justice system to increase the independence, fairness, and efficiency of military courts; and

-

Explain publicly that residency papers obtained by immigrants in one part of the country are valid nationwide.

-

- To the Ivorian National Assembly:

-

Create a special technical committee responsible for examining the continued problem of checkpoint extortion by the security forces; and;

-

Hold public hearings on security force extortion, and call to testify the leadership of the anti-racket unit and military tribunal, senior police, gendarmes, and FRCI and local government officials and community leaders from areas in which extortion is pervasive.

-

- To the Anti-Racket Unit:

-

Investigate commanders who are implicated in or who facilitate extortion and refer perpetrators for prosecution;

-

Work with the military tribunal and civilian justice system to formulate separate cooperation protocols that describe how extortion cases, particularly those targeting commanders, should be investigated and prosecuted;

-

Ensure the protocol discusses, in particular, how to encourage and protect whistleblowers;

-

Increase outreach activities in western Côte d’Ivoire, particularly in the areas of Bloléquin, Guiglo, and Tai, to ensure victims of extortion are aware that they can report incidents to the unit; and

-

Establish regular contact with leaders of communities from neighboring countries to determine where there are problems with discriminatory targeting for extortion and investigate these concerns promptly.

-

- To the civilian and military justice systems:

-

Ensure that extortion cases are investigated and fairly adjudicated in a timely manner.

-

- To Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners:

-

Provide technical assistance to the anti-racket unit, military tribunal, and civilian justice system on how to investigate and prosecute extortion cases, particularly those targeting commanders; and

-

Include training on whistleblower protection.

-