(Rabat) – A Moroccan court on September 12, 2012, sentenced five activists of the pro-reform February 20 Movement to prison terms, and one to a suspended term, for assaulting and insulting police officers after what may have been an unfair trial.

A Casablanca court sentenced them to up to 10 months in prison despite their claim, from the moment they emerged from police custody, that they had been tortured into signing false confessions, the sole evidence against them. The court refused to summon any of the officers who claimed to have been assaulted to appear in court, and heard no witnesses who identified the defendants as having committed any infractions. The defendants plan to appeal.

“The courtsent protesters to jail on the basis of confessions allegedly obtained under torture, while refusing to summon the complainants to be heard in court,” said Eric Goldstein, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Morocco can guarantee fair trials only when courts seriously investigate allegations of coerced confessions and dismiss as evidence any confessions the police obtained improperly.”

Police arrested the six while dispersing a demonstration of several hundred people on July 22 in the working-class neighborhood of Sidi el-Bernoussi, Casablanca. The February 20 Movement has held rallies in cities around the country since the loosely organized group was formed on that date in 2011 to protest corruption, unemployment, the high cost of living, political repression, and the concentration of power in the monarchy. Authorities have often allowed the marches, but at other times violently dispersed them and prosecuted participants on often-dubious charges.

At the July 22 march, the protesters chanted strong anti-monarchy slogans but remained peaceful, participants told Human Rights Watch. At one point late in the evening, the police surged to disperse the protesters. They arrested the six defendants, put them in a police van, and took them to the local police station.

Leïla Nassimi, a February 20 activist who said she still has back pain from a beating in a police wagon, described her arrest and mistreatment to Human Rights Watch:

The demonstration was already over, people were still there but beginning to leave. I was sitting in a café when I saw the police moving in, so I got up to see what was happening. The police grabbed me and put me in the back of their van. Inside the van, policemen started beating me right away. Each time they added someone to the wagon, they beat everyone inside again. They drove us to the Anassi station of the judicial police in Sidi el-Bernoussi. At the station, they did not beat me but I saw what they did to the others in the hallways, before they took us to separate offices: they were slapping them, pulling down their pants, ordering them to shout, “Long live the king!” [One slogan of the February 20 Movement is “Long live the people.”] If they refused, the police beat them some more.

On July 25, after three days of pre-arraignment (garde à vue) detention, the six defendants appeared for the first time before the prosecutor, deputy prosecutor Moustapha Fadioui, who informed them that they were charged with staging an “unauthorized” gathering, assaulting and insulting police as they were performing their job, and insulting the police as an institution.

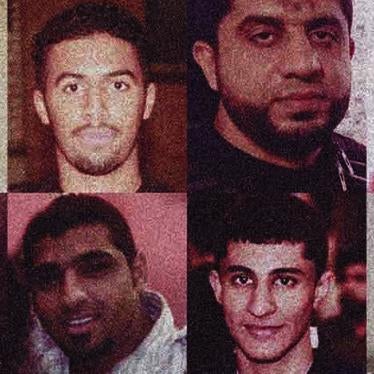

As noted in the official minutes of the hearing before the prosecutor, the six all denied the charges and said the police had tortured them, beating them in the van and, in most cases, again in the police station. One defendant, Tarek Rouchdi, 29, said that at the station, officers pulled off his clothes and inserted fingers in his anus, the minutes say. Another, Youssef Oubella, 23, said the police had pulled out his eyelashes, pulled off his clothes, and inserted fingers in his anus. Samir Bradli, 34, said the police beat him and pulled out his eyelashes.

At the July 25 hearing, injuries were visible and the clothes of some were torn and bloodied, Mohamed Messaoudi and Omar Bendjelloun, two of their lawyers who attended, told Human Rights Watch. The prosecutor notes in the official minutes, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, that he observed bruises and red marks on Oubella’s right arm, and a black eye; a wound on Bradli’s head “perhaps two centimeters long;” bruises and red marks on the right arm of Abderrahmane Assal, 43; small injuries on the nose and neck of Nouressalam Kartachi, 21; and no injuries on Rouchdi. He does not mention Nassimi, 51, in this regard.

The prosecutor ordered a doctor to examine the defendants. The doctor visited the six the same day and filed a one-page report covering all of them, which Human Rights Watch has read. It states that the examination revealed “nothing in particular…no…trauma… [but] a superficial cut on the scalp of Samir Bradli.” The other defendants declared later to the court that the doctor had not physically examined them, Bendjelloun said.

The case was referred to trial before the Ain Sbaâ (Casablanca) First Degree Court. The court provisionally released Nassimi, but ordered the five men, all of Casablanca, held pending the trial.

During the trial, which lasted several sessions and concluded with a marathon hearing that continued until 3 a.m. on September 11, the only evidence linking the defendants to the most serious charge – assaulting the police – was their own confessions and the written complaint by one police officer who said Nassimi bit him, Messaoudi and Bendjelloun, the defense lawyers, told Human Rights Watch. No policeman or witness for the prosecution testified at trial, nor did the prosecution produce any video or material evidence.

The five male defendants steadfastly denied the contents of their “confessions” made before the police. Four said they signed them under torture; Kartachi had refused to sign his, explaining at the trial that he had refused to sign because the police had never interrogated him about the events of that evening. Nassimi told Human Rights Watch that she signed her statement without reading it because she did not have her glasses, and learned only later that in it she had confessed to biting and hitting a police officer, a statement she denies making and that she denied in court.

The case file included written statements by police officers that they had been injured while dispersing the demonstration, with medical reports to support their claims. However, the officers in these reports did not identify the individuals who they say assaulted them, except for the officer who accused Nassimi of biting him, Messaoudi and Bendjelloun said.

The defense asked the trial judge to subpoena the police complainants to court to answer questions, but the judge refused. The file also contained written statements by local business owners mainly complaining that the July 22 demonstration had hurt their business but identifying no perpetrators. These complainants never appeared in court, despite defense requests to have them testify.

Three defense witnesses testified that they saw the police using violence against the demonstrators, not the other way around. The three included one journalist who testified that the police had placed him in their van and beat him, then released him without charge.

Kartachi and Oubella were each sentenced to eight months in prison, Bradli, Assal and Rouchdi to 10 months, and Nassimi to a six-month suspended sentence. The court fined each of the six 500 dirhams (US $55) and awarded 5,000 dirhams (US $550) to each of the police officers who claimed injuries, to be paid by the defendants. The five male defendants are in Oukacha prison.

During the trial, the defendants described the violence, threats, and insults they said the police used to coerce them to sign false statements, and the trial judge questioned them about their assertions. The court has not yet published its written judgment, which may reveal the reasons the court rejected the defendants’ claims of torture. A judge is prohibited from admitting into evidence any statement obtained under violence or coercion under Morocco’s code of penal procedure, article 293.

With regard to the charge of participating in an illegal gathering, the defense invoked the right to freedom of assembly. As a matter of Moroccan domestic law, most public demonstrations require advance notification of the authorities. The February 20 Movement generally does not comply with this requirement, and did not do so for the July 22 event, although it publicly announces its planned actions.

While assaulting an individual police officer is a legitimate criminal charge, criminalizing insults to the police as a public institutionviolates the right to freedom of expression, Human Rights Watch said.

The February 20 Movement says that scores of its members around the country are now in prison after being convicted on charges similar to those filed against the Sidi Bernoussi defendants. In addition, a Casablanca rap music artist active in the February 20 Movement, Mouad Belghouat (known as al-Haqed), is serving a one-year sentence for a song and related video deemed “insulting” to the police as an institution.

“When Moroccan courts begin adequately addressing allegations of the use of torture to obtain evidence, and ensure that the accused have the opportunity to question complainants and all relevant witnesses in court, they will not only ensure fairer trials, but also signal to the police that they need to stop using improper methods to extract confessions,” Goldstein said.