As representatives of about 60 countries and international organizations gather in Chicago for the NATO summit, much of the focus will be on who pays for Afghan security forces in the years ahead. This is an important question, particularly since hundreds of thousands of unpaid soldiers, police and paramilitaries could wreak havoc on the country. But my recent trip to Afghanistan convinced me that the Afghan government and its external supporters need to grapple with a much larger question: What kind of Afghanistan will emerge as NATO withdraws by the end of 2014?

Much has improved over the past 10 years since the overthrow of the Taliban regime. Afghanistan has a vibrant press, many civil society organizations and much better access for women — especially in urban areas — to education, health care and work. But many Afghans are nervous about whether these advances will survive the impending international retreat from their country.

Few think another Taliban takeover is imminent, but other bleak scenarios are envisioned. Some predict a return to the kind of full-scale civil war between different regions and ethnic groups that reduced Kabul and other parts of the country to rubble in the 1990s. Many anticipate that the Taliban will expand its control, particularly in the southern and eastern Pashtun areas. Others foresee further decline in the authority of an already weak central government, unable to stem the growth of local and regional fiefdoms. Local control in Afghanistan often means handing parts of the country to warlords with little tolerance for democratic dissent or women's rights.

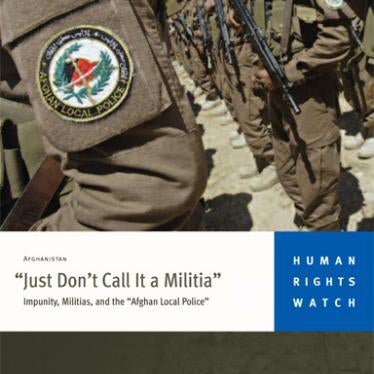

The anxiety of Afghans only intensifies as they look at the human rights record of their government, the large number of human rights abusers in the government and parliament, and the inconsistent actions and rhetoric of President Hamid Karzai. Government-backed militias and the U.S.-supported paramilitary Afghan Local Police have resorted to extortion, assault, murder, rape and forced recruitment. Torture is routine in jails run by the Afghan intelligence service. Accountability mechanisms to prevent and redress human rights violations do not function properly.

A central problem, long avoided by Washington, is the rot at the heart of the Afghan government. In ousting the Taliban, the U.S. deliberately funded and financed power brokers and warlords, many of whom, such as Vice President Mohammed Fahim, have long histories of complicity in atrocities. Karzai is trapped by these men and dependent on them to remain in power.

The surest way for the international community to squander its decade of investment in Afghanistan is to withdraw troops, breathe a sigh of relief and walk away. What is needed in Chicago and thereafter is a renewed and deepened commitment to protect the rights of Afghans through properly trained and vetted security forces. Also critical are accountability mechanisms for abusers, yet the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission is under intense pressure from the Afghan and other governments not to publish a report detailing abuses committed by powerful individuals and factions.

Moreover, in key capitals such asWashington, D.C., London and Brussels, policymakers need to recognize that Afghanistan cannot be rebuilt by men with guns alone.Afghanistan'sdedicated schoolteachers, doctors and lawyers, honest civil servants, courageous journalists and activists need continued financial, political and moral support, and at times, physical protection.

In Chicago and beyond, the risk is that there will be no strategy for anything other than an international pullout. Ten years after the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban, despite regular rhetorical commitments to the rule of law and good governance, it is fair to ask the world's leaders to articulate a clear strategy to protect the rights of all Afghans. How will the security forces being trained by the U.S. and others be professional? How will they be held accountable for abuses? What is the strategy to protect women and other vulnerable communities? How will the international community ensure that girls are not barred from attending school in rural areas, that women are not prohibited from going to work, that the rights of women and girls are not bargained away by the government in a "peace" deal with the Taliban? These are the questions that Afghans are asking. In Chicago, President Barack Obama and others should start providing answers.

Kenneth Roth is executive director of Human Rights Watch.