When I interviewed 20-year-old Tun Tun Aung (not his real name) he had a bullet wound in his shoulder that had shattered his arm.

He was shot escaping the Burmese army early this year, after weeks of service as a front-line porter.

The army usually coerces civilians on Burma’s periphery into this work, forcing ethnic villagers to carry military supplies through conflict zones.

For major military operations, however, they gather hundreds of convicted prisoners, who are considered more disposable. Many do not return. Lucky survivors like Tun Tun Aung escape to Thailand.

Tun Tun Aung told me about the night before he escaped. “The soldiers told us at night that there was a lot of fighting on the mountain, and that if we were alive tomorrow night we would be lucky,” he said. “We are all dead, I thought. Alive or dead, it’s the same thing here.”

He had been sentenced to just 18 months in prison, for brawling with a neighbor in his hometown near Mandalay in central Burma. But then authorities selected Tun Tun Aung from his small prison and sent him across the country to carry supplies in the world’s longest-running civil war.

In January, the Burmese army, in collusion with the police force and the prisons department, transported an estimated 700 convicted prisoners from 13 prisons throughout Burma to carry supplies for operations against ethnic Karen rebels close to the border with Thailand.

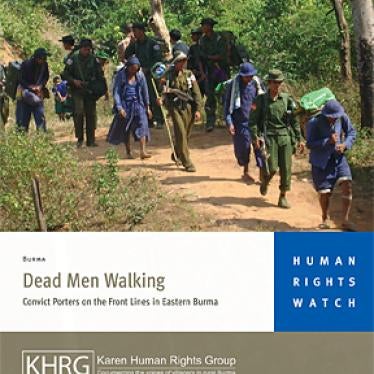

As with Tun Tun Aung, none of the other men volunteered and none received payment, as international law requires. Authorities did not tell them what awaited them until they arrived at front-line military bases, where convicts were issued distinctive blue convict porter uniforms.

The prisoners were a mix of petty offenders, drug dealers and murderers, but their crimes and punishment did not warrant an effective death sentence in service of the army’s ruthless counterinsurgency campaigns.

Their experiences as human pack-mules in rugged, mountainous, jungle terrain, were harrowing. They carried mortar shells, wounded Burmese army soldiers, bullets, rice, cooking oil and water, or anything the Burmese soldiers needed.

It is almost impossible to determine how many porters have perished, or remain in military custody today. Porters died stepping on landmines — often forced by the army to walk ahead of troops as human shields — or in firefights, or they were killed or died from ill-treatment and beatings at the hands of soldiers.

Soldiers would drag injured porters to the side of the trail to bleed to death, or push them over ravines for a quicker death. In his several weeks at the front lines, Tun Tun Aung witnessed 10 convict porters fatally step on landmines.

Another survivor, Maung Nyunt, told me, “We were carrying food up to the camp and one porter stepped on a mine and lost his leg. The soldiers left him, he was screaming but no one helped. When we came down the mountain he was dead. I looked up and saw bits of his clothing in the trees, and parts of his leg in a tree.”

These experiences are not isolated events, but part of a well-documented pattern.

Some Burma watchers hoped the country’s November 2010 elections would lead to gradual improvement in Burma’s respect for human rights. But there has been no change in the army’s brutal behavior against civilians as fighting intensifies in northern ethnic areas.

The mistreatment of convict porters on the front lines is just one of many ongoing war crimes in Burma. The Burmese government has long shown itself unwilling to end such horrific wartime abuses without external pressure.

Sixteen countries have publicly voiced support for a United Nations-formed Commission of Inquiry into violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in Burma, but so far no country has shown a willingness to invest the diplomatic capital to make it a reality.

A number of countries have delayed endorsing an international inquiry, suggesting they are waiting to see if the new government is serious about ending human rights abuses. But each day they wait means more deaths of convict porters, as well as of other civilians, from Burmese army atrocities. Responsibility for the misuse of prisoners as porters and other abuses is borne by the Burmese government. But it will be up to U.N. member countries to ensure that such barbaric practices are stopped.

David Scott Mathieson is a Senior Researcher in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch.