(New York) - The Bangladeshi government should offer its full and public support to a bill before parliament that would criminalize torture, Human Rights Watch said today.

Human Rights Watch urged the government to make parliamentary time for the bill soon and to ensure that the bill is in compliance with the international Convention against Torture, to which Bangladesh is a state party. The bill was drafted by a back-bench Awami League member of parliament, Saber Chowdhury, himself a victim of torture at the hands of government forces.

"Torture is used routinely by law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh," said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. "The bill in parliament presents an important opportunity for this government to show its commitment to upholding the rule of law and to show that it is different from its predecessors."

Human Rights Watch and others have long documented the systematic use of torture and deaths in custody in Bangladesh by its various security agencies. Detainees have been subjected to electric shocks, rape, severe kicking, and beating with objects that include iron rods, belts, or sticks. People taken into police custody, whether criminal suspects, labor union leaders, journalists, or even politicians, have regularly alleged that they have suffered torture and mistreatment.

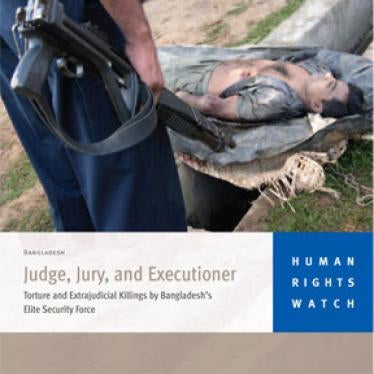

The Rapid Action Batallion and the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), the army's intelligence unit, have routinely engaged in torture, which has often led to the deaths of suspects in their custody. They have used torture as a means to silence dissent and to extract confessions, often making suspects sign blank sheets of paper.

These practices have continued irrespective of the government in power, although they peaked during the recent military-backed caretaker government. At that time, both the Awami League, now the governing party, and the opposition Bangladesh National Party alleged that their members and leaders were arbitrarily detained and tortured. A Human Rights Watch consultant, Tasneem Khalil, was illegally detained by DGFI and tortured in 2007. No one has been held legally accountable in any of these cases.

The security forces themselves are not immune from these practices. Many members of the Bangladesh Rifles accused of involvement in a violent insurrection in 2009 have told the courts that they were tortured to make them confess to being involved. Family members and others who have visited some of the accused have said that they have found them severely wounded and unable to speak or walk properly. A number have died in custody.

"Torture seems to have become the accepted norm among security agencies, both as a method of investigation and as a means of law enforcement," Adams said. "The government knows who in army intelligence was responsible for torturing a Human Rights Watch consultant in 2007, yet the perpetrators have not been questioned or prosecuted. This law could change that."

The Awami League government has admitted that torture continues, though it denies that it encourages or condones the practice. Foreign Minister Dipu Moni, appearing in Geneva before the UN Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review in 2009, made a commitment to carry out a "zero tolerance" policy for torture and other abuses. Yet little has been done to put such a policy in effect.

"Enacting this law will prevent law enforcement agencies from claiming that torture is a legitimate way to extract information from suspects or to punish them," Adams said."After many years of turning a blind eye to an acknowledged problem, the government and parliament have an opportunity to back meaningful change and end this shameful practice."

Although the Bangladesh constitution prohibits torture, there are conflicting laws that effectively shield perpetrators from liability. Article 46 of Bangladesh's Constitution empowers parliament to pass laws that provide immunity from prosecution to any state officer for any action taken to maintain or restore order and to lift any penalty, sentence, or punishment imposed. Soldiers and Rapid Action Battalion officers are protected from the civilian criminal justice system under laws that ensure that they can only be prosecuted in internal courts by their peers through processes that lack independence or impartiality.

While the civilian courts have jurisdiction over cases involving police officers suspected of involvement in criminal activities, such officers are protected by Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which requires explicit government approval to prosecute an officer purporting to have acted in an official capacity. Several other laws state that no legal action can be taken against a person who acts in good faith to implement any of its provisions.

The bill in its current form goes a long way toward closing these loopholes and to meeting the standards set forth under the Convention against Torture, Human Rights Watch said. It would create a simplified process and venue for redress for victims of torture, or others acting on their behalf, and would afford them protection if they want it. It would create a regimen under which public officials would be held accountable for the physical and mental well-being of anyone taken into custody, from the process of arrest onward. The bill, in an important provision, strips away the often cited excuse of public welfare to justify deaths in custody. Under the proposed bill, war, political instability, public emergency, and superior orders could not be used to justify torture.

Human Rights Watch urged the government and parliament to make amendments so that the bill meets the international standards set out in Convention against Torture. The definition of torture should be amended to reflect the language used in the convention, instead of the narrower definition in the current version of the bill.

The bill should also include language explicitly stating that liability for torture extends not only to the actual physical perpetrator but also to those higher up the chain of command who may either have ordered or consented to torture or looked the other way when it happened. The Committee against Torture, set up under the convention, has held that senior officials are criminally liable for acts of torture committed by junior officials.

"Effective change will be possible only when all levels of the chain of command or authority are held accountable," Adams said. "Everyone, from top to bottom, has a responsibility to end this widespread practice."